Blown Slick Series #13 Part 18 (3/3)

The Eastern Solomons became the most intensively studied carrier action yet… Despite intensive analysis, the battle as a whole remained a mystery. Lundstrom

Blindman’s Bluff (3) – An Empty Sea

After the final near miss on the 24th and continued retreat on the 25th, the Enterprise air group was flown off to the Wasp, the Saratoga, and area islands. Freed from duty to the departing aircraft carrier, the North Carolina, the Atlanta, and two destroyers were sent to join the Saratoga group.

After absorbing the brunt of the U.S. carrier strikes and seeing one of his two large carriers damaged, Nagumo decided he had had enough. He ordered a withdrawal to Truk.

First a RememberedSky note: As in the analysis of the Battle of Midway, which leveraged Shattered Sword by Parshall and Tully, this post will lean heavily – both the analysis itself and actual words – on one particular work, in this case Blackshoe Carrier Admiral: Frank Jack Fletcher at Coral Sea, Midway and Guadalcanal, by John B. Lundstrom.

Before jumping into his discussion, two points:

First, it is probably worth a reminder as to the focus of this series as presented in Part #1 Background.

The current Chinese two island chain defense of the South China Sea is at least discussable as not so different from the Japanese approach related to establishing its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, wherein the attacks on Pearl Harbor and Midway focused on elimination of the United States as a strategic power in the Pacific, were an element of that overall strategy.

This series then continues to present for consideration a review of that first year of WW II in the Pacific and the emergence of aircraft carrier warfare as provoking thought on operations in an island chain context.

The intent then has never been to try and tell the whole story of the carriers in the Pacific in 1942, but rather to extract considered points from multiple respected sources as discussion points in the comparison of the time frames. John Lundstrum’s research and writing is a perfect match.

Second, in their analysis of the Battle of Midway, Parshall and Tully noted that failures of anticipation of what the U.S. Navy could or might do were a critical aspect of the IJN defeat. They point out, “The essence of a failure to anticipate is not mere ignorance of the future, for that is inherently unknowable. It is, rather, the failure to take reasonable precautions against a known hazard.” It was clear to them as they researched Midway from the Japanese perspective that the Imperial Navy failed to anticipate as it went into the battle.

As you consider Lundstrom’s points, note that VADM Frank Jack Fletcher was castigated roundly by King, Nimitz and later historians such as Morrison for not being aggressive enough… I.e., for not falling into that same trap of failure to anticipate possible enemy capability.

This aspect has resulted in the adding of emphasis at key points.

TACTICAL LESSONS

[Lundstrom]

[As stated above, this battle] became the most intensively studied carrier action yet. The single overriding complaint concerned communications: poorly functioning radios, delayed contact reports, and other shortcomings in passing vital information. Captain Davis described communications as “weak to the point of danger,” and Admiral Kinkaid stated, “Communication failures are the primary cause of many tactical errors.” Fletcher submitted an entire report on the failure of communications. The problem did not admit to a quick fix and dogged the U.S. Navy for the rest of the year.

… Fletcher called fighter direction “not entirely satisfactory although much better than previously experienced.” The intercept of lone shadowers continued to excel, but the carriers still seemed at a loss concentrating combat air patrol fighters to defeat strike groups. Yet ship antiaircraft improved considerably, and the fast battleship had proven invaluable. At the same time fighter escorts remained weak, particularly for the vulnerable torpedo planes. Some leaders, notably Davis, recommended limiting torpedo planes to moonlight strikes and finishing off cripples, or using them as horizontal bombers. Fletcher strongly disagreed. The aerial torpedo was the most powerful antiship weapon in the air arsenal. His fears for the misuse of torpedo planes soon came true.

The carriers appeared more satisfied with the Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat, although acknowledging its inferiority to the Zero. As noted previously, the only immediate action in the absence of better fighters was to have more Wildcats. Fletcher even desired a dedicated “fighter carrier,” if enough other carriers were available to accomplish the offensive mission. Kinkaid concurred.

Up to this point the carriers depended chiefly on surprise to compensate for numerical or matériel inferiority, but now, in the face of extensive shore-based air, that no longer pertained. Kinkaid rated fighter strength according to the anticipated opposition. For “normal operations” the carriers should each have forty F4Fs instead of the current thirty-six, but against tougher defenses there should be sixty. To conduct amphibious offensives, such as Watchtower, where the carriers themselves must support ground operations, one carrier should have one hundred or more fighters.

Increasing fighter strength, however, correspondingly reduced offensive power in the form of dive bombers and torpedo planes. The whole issue needed careful consideration.

Fletcher continued to oppose the single carrier task forces he was ordered to use on 24 August. His 24 September letter on carrier tactics called for carrier task forces assigned to the same mission to remain together for “mutual support and protection” and not separate “unless there is some strong tactical reason.” In this he followed the iconoclastic Rear Adm. Ted Sherman. Fletcher elaborated these views in his 25 September endorsement of the Enterprise Eastern Solomons Report.

Davis urged the individual carrier task forces draw at least fifteen miles apart in the event of air attack. Fletcher strongly disagreed. “To an attacking air group, it makes little difference whether the carriers are separated by 5 or 20 miles but to the defenders it makes a great deal. By keeping the carriers separated 15–20 miles there is always the danger that the full fighter force may not be brought to bear decisively against the enemy as happened at Midway.” Davis opined, “The joint operation of more than two carrier forces is too unwieldy.” Fletcher countered that according to “our recent experiences” a task force commander could handle three carrier task forces “almost as easily as two.” Even four could operate together “without too much difficulty.” The “advantages to be gained from such a concentration of air power would more than offset any disadvantages.” He prophesied the “tendency will be to operate more and more carriers together as our offensive gains momentum.”

MAKING SENSE OF THE EASTERN SOLOMONS

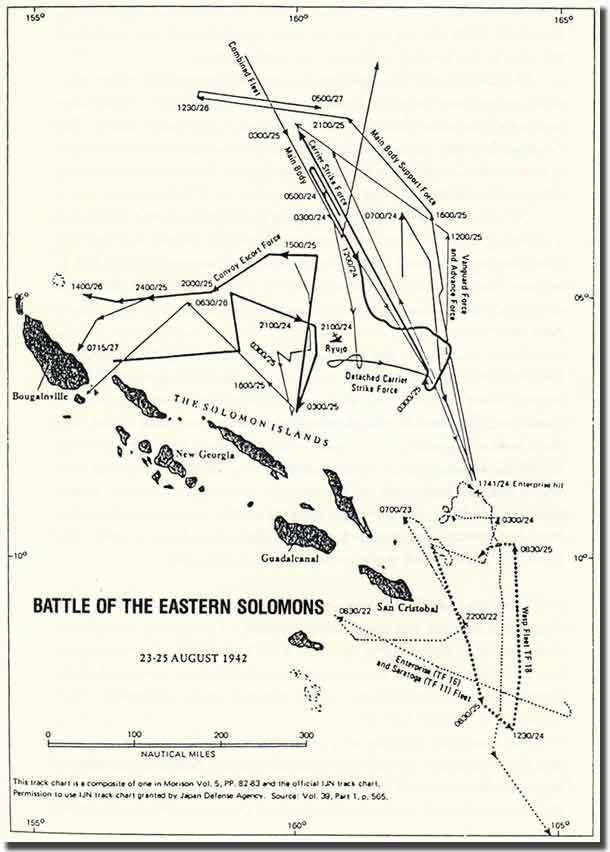

Despite intensive analysis, the battle as a whole remained a mystery. The exceptionally poor communications and numerous failures by the search to report correctly the enemy’s strength and position rendered Fletcher, [as explained to Samuel Elliot] Morison, “Thoroughly confused throughout the action.” Fletcher thought there were at least two and very possibly three separate enemy carrier task forces with four flattops. Due though to the “incompleteness of last contact reports,” he could not “fix with any degree of accuracy” their positions.

Fletcher’s 6 September 1942 preliminary report designated “Task Force A” the group of ships he thought included the light carrier Ryujo, which the Saratoga’s aviators claimed to have sunk. He speculated the Ryujo launched the evening strike that fortuitously missed TF-61.

East of Task Force A was “Task Force B” with the big carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, which likely dispatched the huge strike of eighty aircraft that hit TF-16. [One] mini-strike very likely targeted B’s screen, possibly damaging a battleship and two cruisers. Fletcher supposed another light carrier force, “Task Force C,” operated southeast of Task Force B and was the source of the Cactus-bound strike detected early that afternoon on radar.

[RS: Note how different Fletcher’s perception of the battle was from reality]

The confusion persisted long after the battle. The Ryujo remained in the Cincpac intelligence bulletins for a week. Ghormley told Nimitz on 3 September it was likely Fletcher’s and McCain’s bombers hit different carriers and that the Ryujo was just badly damaged. [It was noted]… in late 1943, “[The] consensus of those of us who were there is that there were 4 Jap carriers.” Of course, only three Japanese carriers fought in the Eastern Solomons. The phantom Task Force C resulted from misidentification and incorrect navigation by search planes and Sewart’s B-17s. Even nailing down the loss of the Ryujo proved difficult. The cryptanalysts were not certain until January 1943, when they deciphered a naval message that deleted her from the navy list.

The other fundamental question raised by the battle was how the Japanese carriers could reach the Solomons without radio intelligence predicting and confirming their movements. Fletcher discussed the intelligence failure with Nimitz when they next met. He brought up the Cincpac daily intelligence bulletin, received on 23 August, placing all Japanese carriers north of Truk, where instead, as many as four flattops had secretly closed within a few hundred miles of TF-61. According to Layton, Fletcher “cussed so loudly about the intelligence being bad,” but he was not the only one deeply concerned. Even while the battle raged, Captain Steele’s daily summary of radio intelligence had noted: “It now seems probable that Jap CVs are about to enter Truk. If this is so they can hardly arrive in the Solomons before August 27th, local date.”

The day after the battle Rochefort’s Hypo analysts admitted their bafflement. “Success of a large task force including carriers in reaching the Solomons without detection by R.I. indicates that radio security practices of the Japs are effective insofar as concealing actual movements is concerned.” The experts finally deduced the initial inclusion of the carrier forces in the local communication net really meant they were already present instead of just en route. Layton later decided the reason the expected carrier arrival report at Truk had not been intercepted was that, unknown to the Allies, the striking force bypassed Truk and kept going south. In the end, “You can’t always be right,” and “that’s what RI is all about.”

Despite an at least temporary strategic victory in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, many thought Fletcher should have done much better. He should have taken advantage of what they perceived was a highly advantageous tactical position on the evening of 24 August. The extremely exaggerated claims of aircraft destroyed in the attack on TF-16 (at least eighty-four planes shot down by combat air patrol and antiaircraft), as well as tantalizing hints from radio intelligence of additional heavy plane losses, had mesmerized Nimitz. His preliminary report postulated that 24 August cost the enemy “the best part of three or four carrier groups destroyed in action,” or “most of the Japanese aerial striking force available that day.” The eighty planes that were annihilated assailing TF-16 represented “at least one large and one small carrier group.” Moreover, “The second attack group that missed locating Task Force 61 late in the afternoon could have been the other large carrier air group,” whose “planes were later in the evening heard trying to home their carrier.” Thus, Nimitz speculated, “Some or all of the group were lost.”

Given confusing reports of twin-engine bombers attacking Cactus on 24 August, he was uncertain whether carrier planes also struck Henderson Field, whose defenders claimed eleven single and twin-engine bombers and seven fighters. “If so, the Japanese lost the best part of three carrier groups in the action of 24 August, and perhaps much of a fourth if a carrier group joined in the attack on Guadalcanal.”

Consequently, “Not only was the enemy landing expedition turned back, but we had definitely won control of the air.” At the same time Fletcher’s own air losses (sixteen planes) were extraordinarily low. Despite damage to the Enterprise, “We still had intact practically two full carrier air groups.”

At the same time, the “Wasp Task Force was fueled and proceeding North to join TF-61 as it retired southward. The Hornet Task Force was nearby enroute.” Therefore Nimitz strongly regretted that Fletcher withdrew the Saratoga group and wasted all 25 August refueling. At the same time Noyes’s TF-18 merely “took position in the general area southeast of Guadalcanal prepared to repel further Japanese attack.”

In his ignorance of actual events, Nimitz was extremely unfair.

The final Cincpac battle report, dated 24 October 1942, not only repeated the earlier comments regarding heavy enemy air losses, but also strongly questioned Fletcher’s actions: “The withdrawal of the Saratoga Task Force on the night of 24 August broke off the engagement. At this time the enemy carrier air forces were depleted. Based on hindsight it appears that had the Saratoga group remained in the vicinity occupied on the 24th, they might have been able to strike the enemy with air and probably surface forces, since the Japanese heavy units continued to close during the night and did not reverse course until the forenoon (afternoon for some groups) of 25 August.”

Cincpac described Japanese vulnerability on 25 August not only to carrier air attacks, but also surface combat from Fletcher’s task groups. “We must use our surface ships more boldly as opportunity warrants.” However, “The distances involved, the problem of coordinating widely scattered forces, along with inadequate communication facilities and training, together prevented the victory from being as decisive as it should have been had planes and surface forces come to grips with the enemy after his air forces were largely destroyed on the 24th of August.”

The Cominch 1943 Battle Experience Bulletin echoed Nimitz’s opinion of poor leadership at Eastern Solomons. “Task forces must anticipate repeated attacks and be prepared to repel them and not be in an unprepared and disorganized condition,” referring to TF-11 on the evening of 24 August. “Our task force took the defensive more than the offensive,” whereas “effort should be made to follow up initial successes in order to completely annihilate the enemy whether it is daylight or dark.” On 25 August, however, the “attitude was too defensive,” especially because “an offensive by Task Force 18 might have resulted in complete destruction of the enemy.”

Of course, the tactical situation Fletcher actually faced on the evening of 24 August was far less sanguine than Nimitz and King ever appreciated.

They considered the supposedly decimated Japanese easy pickings for the Saratoga and Wasp flyers had Fletcher only mustered the courage to stay and fight. In fact, Cincpac vastly overestimated Japanese carrier plane losses. The actions on 24 August cost the Shokaku and Zuikaku just thirty-three aircraft. Far from having his air groups “largely destroyed,” Nagumo enjoyed his full aerial torpedo capability of thirty-four carrier attack planes and retained half his dive bombers, as well as forty Zero fighters.

The battleships, cruisers, and destroyers led by Kondo and Abe were too formidable for Fletcher to take on alone in surface combat. As so often, the operative word is HINDSIGHT.

Just a spectator to the attack on TF-16, all Fletcher had to go on that evening, while he deliberated whether or not to withdraw TF-11, were the initial impressions of tired fighter pilots who landed on the Saratoga. That night it looked as if three of four enemy carriers remained untouched, and that powerful surface forces closed fast. He did not gain a fuller picture of the defense of TF-16 until after contacting Kinkaid the next afternoon. The compilation of victory claims only came after collating the action reports.

Criticism of Noyes as merely standing toward Guadalcanal instead of seeking to engage carriers to the north was extremely unjustified. Noyes went where he thought the enemy’s main body would be. He did not find it, because the Japanese themselves pulled out. Nimitz’s mention of the Hornet task force being nearby was especially misleading. During the battle TF-17 was fully one thousand miles away and could not possibly have intervened for several days.

The negative impression persisted of Fletcher’s failure to pursue. Morison partially heeded [the] explication that the battle “exemplified the difficulties in the exercise of command at the point of contact. [and reflected that] his problems were sufficiently great to justify some of the errors.”

In truth Fletcher’s problems were far more profound than [a great many senior commanders] ever understood. Enjoying better, but by no means comprehensive, access to Japanese records than wartime analysts, Morison conceded when Fletcher “decided to call it quits for the day,” he was “amply justified” in escaping the charge of Kondo’s “sea-going cavalry force.” Morison favorably compared Fletcher’s decision to the wisdom Spruance demonstrated on the night of 4 June in backing out of harm’s way at Midway. “It was not known whether the Japanese had had enough, but it was clear that their available gunfire power was much greater than Fletcher’s, and night was no time to test the truth of this estimate.” Yet Morison condemned what he, too, perceived a lack of an aggressive spirit combined with Fletcher’s characteristic obsession with fuel. “How badly did his destroyers need that drink of fuel oil for which he took Saratoga completely out of the battle scene on the 25th?” Instead, “As long as the issue was in doubt, every available carrier aircraft should have been used to protect our tenuous lease on Guadalcanal. That is what they were there for. Fletcher won the battle to be sure; but only because the Japanese were more timid than he.”

Fletcher’s decision to withdraw was tactically wise; [H]e did need to fuel his destroyers and the rest of TF-11, for that matter, to permit the extended high-speed operations that renewed battle would demand. Vandegrift already had as many or more carrier planes as Cactus could handle.

Fletcher always had to keep in mind that only the intervention of the Japanese heavy fleet forces would ensure in the end whether or not the marines held Cactus. Their carriers were his primary objective. Kondo and Nagumo in truth withdrew their fleets not from timidity, but overconfidence. They would be back, and Sopac ready to meet them, in part due to Fletcher’s well-measured responses during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons.

Morison’s final verdict, “American movements too were unaggressive, largely from want of intelligence about the enemy,” is a fair assessment.

So, however, is Nimitz’s considered judgment that despite all Fletcher’s perceived failures to take advantage of the situation, the Battle of the Eastern Solomons was “a victory that turned back the first major assault of the Japanese to regain Guadalcanal-Tulagi and gave us several weeks of valuable time to consolidate positions there.”

John B. Lundstrom

Blackshoe Carrier Admiral: Frank Jack Fletcher at Coral Sea, Midway and Guadalcanal.

Naval Institute Pres.

****************************

COMMENTS

A week after the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, VADM Fletcher’s flagship USS Saratoga was struck by a torpedo fired by Japanese submarine I-26 which caused a number of significant issues. After making temporary repairs at Tonga, Saratoga sailed to Pearl Harbor to be dry docked. It did not return to the Southwest Pacific until arriving at Nouméa in early December.

Admiral Fletcher was reassigned to shore duty command.

It should be noted that VADM Fletcher was the Task Force Commander of three of the four major naval battles in 1942 (Coral Sea, Midway, Eastern Solomon Islands). His command sank 6 Japanese carriers; 1 at Coral Sea (Shoho), 4 at Midway (Soryu, Kaga, Hiryu, Akagi) , and 1 at Eastern Solomon Islands (Ryujo) and lost 2 American carriers; 1 at Coral Sea (Lexington) and 1 at Midway (Yorktown ). He spent all but 51 of the first 289 days of the Pacific War (7 December 1941 to 21 September 1942) at sea, most of that time in or near enemy-controlled waters.

In October: Part # 19 – The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands