Blown Slick Series #16

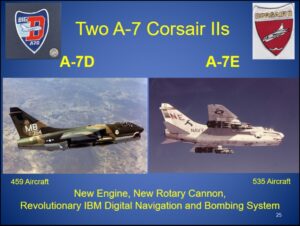

The A-7A/B should be recognized as the end of the line for pure, iron bomb dive bombers including most famously the Dauntless and the A-1 Skyraider, and the A-7D/E as the beginning of a new era of attack a/c – same airframe and aerodynamics but with a major improvement in the systems/avionics. It is not unreasonable to state that the F/A-18 and F-35 have at their core a technical and operational capability that is Corsair II D/E in design concept technically and philosophically – what we now characterize as “strike fighter.” (F-16, F/A-18, F-35)

The story of the A-7 evolution is a central piece of RG Head’s book, reviewed in the previous post. The following is an excerpt by RG from that story.

The Navy developed the A-7 Corsair II in 1963 to replace the venerable A-4 (A4D). In 1965 the Air Force joined the program, and together they developed the A-7D and E with a revolutionary avionics/weapons delivery system. This is the story of that innovation.

The Requirement for the A-7

The Navy bought the A-7 Corsair II in 1963 to meet the requirement for a replacement for the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk. The initial Program Manager, Captain Carl Cruise, described the Navy’s requirement for the aircraft:

“The A-7A was laid out pretty clearly in the [Sea-Based Air Strike] Study that was made by the Chief of Naval Operations. It was to be a simple, not-sophisticated avionics suite, daylight, visual aircraft with long range and large bomb-carrying capability. So, there was never any real question about what the A-7 was supposed to be. Then all this started to change.”

The Air Force Joins the Program

When the Kennedy Administration adopted the National Security Strategy of Flexible Response, the Army challenged the status quo by campaigning to take the Close Air Support (CAS) mission from the Air Force. To make the challenge real it began development of a high-speed, heavily armed helicopter (the AH-56 Cheyenne). Many officials in Robert McNamara’s Office of Secretary of Defense (OSD) supported the proposal and urged the Air Force to develop a specialized CAS airplane. Specifically, there were three analysts in OSD who advocated the concept of a simple, light-weight, inexpensive airplane for CAS: Russ Murray, Pierre Sprey and Herb Rosenzweig. After two computer studies, the Air Force finally proposed in 1965 to join the Navy A-7 program. Colonel Robert E. Hails was selected as the Air Force Deputy Program Manager.

The Air Staff, Tactical Air Command and Col Hails had three problems with the Navy’s design: 1) the aircraft was underpowered; 2) the guns were outdated and unreliable; and 3) the avionics were primitive and ineffective. All three were issues of quality.

The Navy A-7A and B used the Pratt & Whitney TF-30 engine left over from the F-111 program. The thrust was less than 10,000 pounds, but this low thrust was further hampered by steam injestion from the catapult. Engineering attempts to add an afterburner proved futile. After an extensive search, Col Hails found a more powerful Rolls Royce Spey TF-41 engine that increased the thrust by 50 percent!

The Navy guns were two 1940’s MK-12 slide cannons. They had an acceptable rate of fire of 1,000 rounds per minute but were inaccurate and unreliable as verified by F-8 Crusader pilots in Vietnam. The Air Force had upgraded the cannon in the 1950s and adopted the 20 mm M-61 rotary Gatling Gun with a rate of fire of 6,000 rounds per minute. Col Hails insisted the M-61 be included in the Air Force version, and Secretary of Defense McNamara directed the Navy to do the same.

The Avionics Revolution

The change in the avionics suite was a more difficult problem. The initial Air Force requirement was that the avionics should provide for “aided visual weapon delivery” and “no canned delivery.” In April 1966, this was modified to be “an improved system,” using the Navy’s analog computer and a “servoed sight.” The option for a digital computer had been rejected specifically.

CAPT Cruise explained in impact of a new officer in the Program Office:

We were learning more about the CP-741 [analog] bombing computer; we could see that while we were going to get improvements, we were not going to get quantum jumps in improvements, and our accuracy would still be something to be sought. It was about at this point that Bob Doss came on the scene and relieved me of the Navy part of the program and became the Navy Deputy. Bob was something of an expert in this area having been out at China Lake and worked closely with efforts out there to improve bombing accuracy. So, he had a large influence on what happened after that. That’s about the only way I know to express it, that Bob had a large influence on how the A-7E turned out to be configured.”

This turned out to be the understatement of the year.

Robert F. Doss, Commander, USN (already selected for Captain) had been one of the youngest Navy pilots to fly the F2H Banshee in the Korean War, had been an A-4 squadron commander, served as a test pilot at China Lake and had just returned from a Vietnam combat tour. He earned a BS in aeronautical engineering from Georgia Tech and a graduate professional degree from Cal Tech. He had completed both the Naval Postgraduate School and the Naval War College. He was the quintessential innovation advocate.

Bob Doss and Bob Hails immediately hit it off and became collaborators. Bob Doss tells:

“He had his RAD [Required Action Directive], which was a system that wouldn’t work, and he knew it. His requirement was crazy. Basically, you couldn’t get the kind of CEP {circular error probable) they wanted with the equipment specified. The way I looked at the situation was this: the Air Force were going to come and make a major change to the airplane. They were going to put the M-61 gun in it, a different engine and probably a 33-50 percent fuselage change.

Undeterred, CAPT Doss and Col. Hails began researching avionics capabilities with major manufacturers. CAPT Doss described:

“Bob and I started around the country going to all the well-known contractors—Sperry, North American, Hughes, IBM and LTV. We were having trouble with LTV, and we started right out to tell the primes [contractors] that we talked to—the avionics primes—that we were seriously considering an associate contractor to do the avionics and to provide the avionics GFE [Government Furnished Equipment] to LTV to incorporate in the airplane.”

The discussion that follows expresses aircraft bombing accuracy in terms of mils, in which an error of one mil will cause a miss distance of one foot at a distance of 1,000 feet. For example, if an airplane drops a bomb at a slant range of 4,000 feet, a 1 mil error would be 4 feet and a 10-mil error would be 40 feet. General Momyer, commander of Seventh Air Force in Vietnam, estimated the average bomb error in combat was 420 feet. If the average bomb release altitude was 10,000 feet in a 45-degree dive, and a slant range of 17,070 feet, that accuracy would translate into 25 mils. CAPT Doss continued:

“There was about a year where we were doing considerable trade-off studies in avionics, and Bob Hails started getting involved. The trade studies were fairly straight forward with a pretty direct objective. The Air Force position—and I support it—was, ‘OK, we’re going to get a ground attack airplane . . ..’ They established some requirements which were: ‘If I’m going to go into the ground support business, I want an airplane that can deliver a bomb on target, and a target I’ve preselected. So, we want some accuracy for bomb delivery. You [LTV] tell me that you have a 20-mil system in the A-7A; that’s not good enough for us. We want to look at what we can get for what cost?

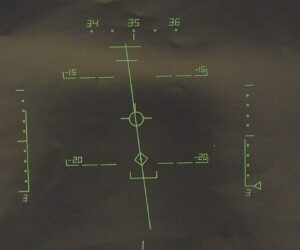

“So, we started a long series of trade studies, looking at different types of systems from the A-7A simple analog, to a more sophisticated analog, to a digital system, and eventually to a heads-up display from the point of pilot training and what it might do to increase accuracy for a novice pilot to do, just as good as a top-notch pilot.”

There was an initial misunderstanding between LTV and the Air Force over the avionics improvement. This difference was highlighted when Colonel Hails went to Dallas in the fall of 1966 with his RAD for increased accuracy. LTV tried to talk Hails out of changing the avionics in the A-7. Colonel Hails emphasized:

“I think this is important. LTV thought they were selling the Navy an airplane for the Air Force instead of selling the Air Force an airplane for itself. They had done business with the Navy for 25 or 30 years [actually 50] and never had a major Air Force program. They had no philosophical understanding of the way we go about establishing requirements, and how we buy airplanes, and who has what authority in the Air Force.”

The president of LTV Aerospace confirmed Hails concern. Navy contractors were used to going over the head of the Navy Program Manager to higher ups in the Navy.

The revolutionary change in the A-7 also induced a revolutionary change in industry. Not long after Hails and Doss insisted on the upgrade of the avionics, LTV made a top management decision to change program managers from aeronautical engineers to avionics system engineers. The chief beneficiary among them was Mr. Robert Buzard, an avionics specialist who tackled the digital avionics issue with a passion.

Selling the Innovation

Doss and Hails commissioned four separate studies, each focused on outlining the best avionics suite for the two A-7 models. CAPT Doss:

“We didn’t let it stay at that by just letting the prime contractor do the studies; with Bob Hails’ concurrence I went to the Naval Air Weapons Center at China Lake and gave them a Weapons Task Study. However, the ILAAS system had been run by the Naval Air Development Center at Johnsville, Pennsylvania, . . . so I integrated a Johnsville team into the China Lake Team. The purpose here was to have an independent avionics configuration study. I met with them nearly every week, either in Johnsville or Washington or at China Lake, and I ran the study myself. We had LTV membership in the team so that we had a totally integrated, multiple thrust study effort. I knew exactly what I wanted for the airplane. I wanted to settle all the debate in-house and to leave no issue for the DOD [OSD] staffs to pick on. And it turned out to be extremely effective, because when it came time to present it, we just said, ‘Study A says that: Study B says that; Study C says that; we all say that; OPNAV agrees, and the Air Staff agrees.’ What could they do?”

Armed with this information and logic, the two deputy program managers began briefing their chains of command. Col Hails explains:

“We had two ‘dog and pony’ shows; I went with them to present theirs to Admiral Connolly . . . and I took it up through the Air Force channels. By then we had a complete change in the guard in the Air [Force] Council. The whole cell had changed when I went back through there in 1967. Their attitude this time around, the Air Staff said they thought that we should go this route if we were going to invest in the airplane. (They gave me hell every time I went in there [in 1966] because the price had gone up.) I gave them outside limits on the price, and there were no real ardent or vocal antagonists for the airplane at that point in time.”

The Final Briefing to OSD

Service approval was not enough. OSD approval was needed. The audience included representatives of several offices. The Systems Analysis representative was Herb Rozensweig. CAPT Doss expected the March 1, 1967, briefing would be a confrontation.

“The critical one was where we finally came together, and we had the Navy and Air Force in agreement, and we went to DOD [OSD] to say, ‘This is what we want to do, and this is why.’ DDR&E bought it, lock, stock and barrel and supported us against Systems Analysis. At the end of the briefing, I said, ‘This study says this, and this study says this,’ and what could they do? Rosenzweig got up and left the briefing!”

Aftermath

Despite the climatic and universal decisions that the avionics innovation was approved, it took Col Hails another six months to get guarantees from LTV for accuracy, reliability and correction of defects. LTV wanted to guarantee 15 mils but not 10. The issue was not resolved until Col Hails raised the issue to the Air Force Secretary. Dr. Brown worded a strong letter to Mr. Clyde Skeen, President of LTV, Inc., the parent company of LTV Aerospace on October 18, 1967. Mr. Skeen replied two days later and apologized, offering to cooperate in every way. He wrote:

“I acknowledge with regret that we should have realized sooner than the system requirements and operational philosophies differ in some respects between the Air Force and Navy, and this undoubtedly contributed in part to the impression in some quarters in the Air Force that we, as a contractor, were unresponsive and non-cooperative.”

Two days later, LTV agreed to the Air Force’s terms and signed the contract.

The Revolution in Operational Accuracy

The results of the innovation in avionics were immediate and revolutionary. Flying the A-7D verified the accuracy of the system:

- “I still firmly believe that the A-7 is the best close air support aircraft flying today. The A-7D was manufactured with a 10-mil error or less. That was part of the specs. LTV met those specs and more. The pilot average was better than that, including flying combat in Southeast Asia. The accuracy was closer to 7 mils.” Col Erv Ethell, 354th Tactical Fighter Wing

- “The A-7E was the most accurate Navy bomber to date, managing four to six mils during Armament Service Acceptance Trials in 1970.” Norman Friedman, author of the 2022 volume of Naval Institute’s U.S. Navy Attack Aircraft: 1920-2020

- “The A-7D and E were the first light attack aircraft to have a good inertial platform and computerized weapons delivery system that I flew. The A-7 system was so good that it was not uncommon for a four-ship of A-7D’s to go to the range with 6 bombs each and return with 24 bullseyes. A bullseye in the A-4 was earned the hard way. When the Air Force built the F-117 stealth fighter, they used the A-7 weapons delivery system.” Terry Wolf – A-4E in combat in Vietnam and the A-7D with the South Dakota Air National Guard.

- “Besides my A-7 time, I logged over 1,500 hours in the F/A-18A and the F/A-18C. The good news about the F/A-18 is that McDonnell Douglas (MacAir) grabbed a bunch of A-7 guys and asked them to help design the cockpit. MacAir also looked at the A-7 HUD and PMDS [Projected Map Display Set] and made them a lot better in the Hornet when they developed the ‘glass’ cockpit. Greg Stearns – transitioned from the A-7E to the F/A-18 and commanded a Hornet squadron

The Effect on the Innovation Advocates

The assessment of their performance as unrelenting advocates for innovation was different for the two officers. Air Force Colonel Robert Hails was promoted three times and retired as a Lt. General. Navy Captain Robert Doss received an unfavorable fitness report from the A-7 Program Manager and retired the following year.

This article is one in a series of stories drawn from the author’s US Attack Aviation: Air Force/Navy Light Attack 1916 to the Present (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military, 2022). The direct quotations were recorded by the author in interviews with the principals for his PhD dissertation on the A-7 program and are referenced as interviews in his book.