Testimony of Pilot #36

I’m 104 and the last survivor of the Battle of Britain – I want to live to 106 to see my crashed plane fly again.

Group Captain John “Paddy” Hemingway is the only surviving pilot of the 2,937 who helped to win the Battle of Britain.

Group Captain Paddy Hemingway.103, is united with a World War11 Hurricane at Casement Air base Baldonnel Near Dublin Ireland Paddy baled out of his Hawker Hurricane over the Thames Estuary After after a dog-fight with German Me 109 fighters. He landed safely near Pitsea his aircraft diving into Fobbing Creek Essex.

“I’m not a great man – I’m just a lucky man.”

So says the Irishman who is the last known surviving member of the group Sir Winston Churchill famously described as “the few”. Group Captain John Hemingway, now 104, was a fighter pilot in the Battle of Britain. He now lives back in the city he was brought up in – Dublin – and credits “Irish luck” with helping him survive being shot down four times.

At 3pm on August 26, 1940, during one of the toughest weeks of the air war to save Britain from German invasion, Paddy was shot down over the Essex marshes. He managed to bail out but his Hawker Hurricane fighter — number P3966 — hit the ground at 400mph, burying itself nearly 40ft deep in the soggy sea bog close to Pitsea. Paddy landed safely near the Barge pub, was found by the local Home Guard and by 10.30pm was back with the men of 85 Squadron to fight another day.

For more than 50 years P3966 lay buried — only a dip in the earth giving a clue as to what lay beneath. In the 1980s an attempt was made to dig it up, but at the time the wreckage was found to be too deep to recover. Then, in 2019, a team finally pulled out the remains of P3966, including the control column — still set in the “fire” position that Paddy had engaged to shoot at the German Dornier Do 215 light bomber that would bring him down. Incredibly, after nearly 80 years in the marsh mud, one of the plane’s eight Browning .303 machine guns was still in working order when removed, and had to be deactivated.

And now the plane is being restored — making it one of the most important artefacts of the Battle of Britain – July until October 1940. The Battle of Britain is a unique moment in history and this plane symbolizes it.”

P3966 is being slowly restored from scratch, by a team of highly skilled engineers from Hawker Restorations in a hangar at Elmsett Airfield in Suffolk. Pilot Tom Smith, 28, bought the wreckage and the Civil Aviation Authority has given him permission to have the plane restored to airworthy standard. After almost a year of painstaking work, the fuselage, wings, and cockpit are now taking shape. As many of the original parts as possible will be retained — including bullet-riddled armor and the manufacturer’s plate with the registration number.

Smith, 28, bought the wreckage and the Civil Aviation Authority has given him permission to have the plane restored to airworthy standard. After almost a year of painstaking work, the fuselage, wings, and cockpit are now taking shape. As many of the original parts as possible will be retained — including bullet-riddled armor and the manufacturer’s plate with the registration number.

But since the invasion of Ukraine 18 months ago, the price of spares and the special steels needed for this Hurricane have gone up dramatically, by fourfold in some cases. Tom, whose family owns the former wartime airfield at White Waltham, Berks, says: “It is getting harder and harder to find the materials to make the parts and to find the people with the skills required to do it. “You might not see another restoration from the ground up like this again. It could be hard to get another one in the air.”

Experts believe that when it is completed in two years’ time, P3966 will not only be priceless but possibly the most prized restoration from the Battle of Britain. Chief engineer Peter Johnson says: “It’s certainly the most important plane that Hawker has restored. “It’s not only a Battle of Britain aeroplane but, remarkably, the pilot is still with us.” Only one of the 740 Hurricanes that took part in the Battle of Britain is still flying today, so P3966 will be a truly historic sight when it takes to the skies once more.

At his care home, father-of-three Paddy has seen photos of the restoration of his old plane taking shape. He says: “I’d love to get to my 106th birthday and see P3966 take to the skies once again. I’ve never forgotten that day when I was shot down over Pitsea Marshes. I still get flashbacks of smoke and burning rubber. I think we lost 11 pilots that time. You had to be lucky. I had bags of luck, and here I am. It’s either being Irish or being lucky — one or the other. If you are both, you are really lucky.”

Born in Dublin in 1919, John Hemingway joined the RAF in 1938 and, following the outbreak of the Second World War, was assigned as a fighter pilot to 85 Squadron in France flying the Hawker Hurricane. During the Battle of Dunkirk, he flew supporting missions over the Channel, before flying in daily sorties during the Battle of Britain throughout the summer of 1940. He was credited with destroying a Heinkel He 111 bomber and a Dornier Do 17. On 1 July 1941 Hemmingway was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) and mentioned in dispatches.

One of his most prominent memories is of Flt Lt Richard ‘Dickie’ Lee. “He was incredible – a wonderful pilot. Dickie Lee could do anything – fly across an airfield, upside down, firing at a target and hitting the target.” Dickie Lee was one of more than 500 of John’s fellow pilots who were killed during the Battle of Britain.

John’s Squadron leader was Peter Townsend, later the fiancé of Princess Margaret. “He was a very nice person and a very good leader, he always went in first.”

Peter Townsend is standing with John and eight other men in uniform in front of a Hurricane in one of John’s photographs. Hemingway, second from left in this photograph, with Townsend center, holding a cane. When asked what his thoughts are about the picture, he says: “They were first-class pilots. “There are lots of aces in this photograph.” But he points to himself and chuckles: “That’s not one of them!”

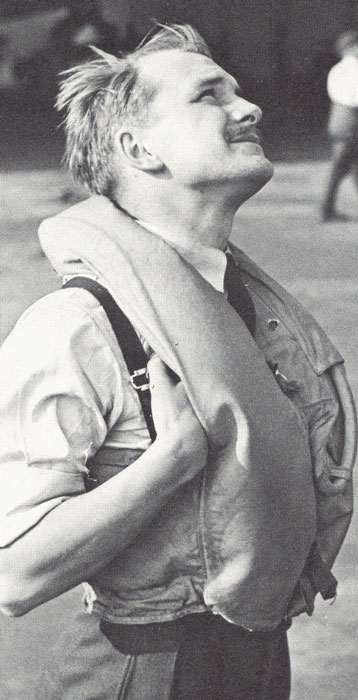

Another photograph of John featured on the cover of the American magazine Life shows him looking up to the sky. Hemingway says this was the photograph that allowed his family to see what he did at work “This was the most important photograph ever taken of me, it made me into a fighter pilot in the eyes of others. It meant my family were able to see me at work.” The image is now captured in a sculpture of John by the artist Stephen Melton at the Kent Battle of Britain Museum.

shows him looking up to the sky. Hemingway says this was the photograph that allowed his family to see what he did at work “This was the most important photograph ever taken of me, it made me into a fighter pilot in the eyes of others. It meant my family were able to see me at work.” The image is now captured in a sculpture of John by the artist Stephen Melton at the Kent Battle of Britain Museum.

Group Capt (equivalent to Army, USAF, or Marine Colonel or Navy Captain, O-6) Hemingway was shot down four times during the war. Two of those occasions happened in the space of eight days – during the Battle of Britain. He recorded in his logbook that on 18 August 1940 he bailed out of his Hurricane near the Thames Estuary after it was hit by a German aircraft. “If you didn’t bail out you knew you would be dead,” he says. He parachuted into the North Sea and was eventually rescued by a lifeboat. He says the thought of being in the ocean, and not knowing whether he would drown or live, was dreadful. “You felt all the time you were part of something which would save you. But if it ever came to the point where you were just alone that would have been quite horrible.” He was back in a plane two days later.

The last incident was in 1945 when he was flying a Spitfire behind enemy lines in Italy. Local people helped to put him in the hands of the Italian resistance and he was taken back to Allied troops. At one point a young girl, who he thinks was only about seven years old, led him by the hand past scores of German soldiers. He went on to be part of the planning for D-Day before flying Spitfires in Italy.

He explains the approach airmen took during one-on-one aerial combat – known as ‘dogfights’ – which were often over in just a few seconds. “There were two of you. One of you was going to be dead at the end. You thought: ‘Make sure that person was not you.’ Every day, off you went. When you took off you knew some of you would come back – and some of you wouldn’t.” Paddy says they used to get into trouble for having dogfights with ME109s, as shooting down fighters would not win the war, and could lead to losing valuable pilots and planes. “The job of the Hurricane pilots was to shoot down the bombers.”

Prime Minister Winston Churchill said of the pilots: “Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few.”

Paddy says: “It didn’t mean anything at the time, although we knew he was talking about us. I suppose we must have felt proud. When all of your friends are gone, that still means something, even now.” While the battle in 1940 was a turning point in the conflict, his recollections and reflections on the war are focused on his role as a professional pilot and has never looked for accolades or fame for his part. “I don’t think we ever assumed greatness of any form,” he told the BBC. “We were just fighting a war which we were trained to fight -doing a job we were employed to do. We just went up and did the best we could.”

John thinks of all those who came to his aid during the war with “huge gratitude”. “They were brilliant people – they risked their lives.”

He modestly puts his long life down to luck, specifically, “Irish luck”. “It must be to do with something like that because here I am, an Irishman, talking to you. I was shot down many times but I’m still here. So many others were shot down first time and that was the end of them.”

“I was lucky. And I’m still lucky.”

Fighter Pilot

John Paddy Hemingway – Last of Winston Churchill’s “FEW”