… a fundamental transformation in naval power had just taken place. Carriers usurped the prime strategic role of battleships in that their principal opponents were their enemy counterparts, and they should only to be committed to battle in the proper circumstances .. Lundstrom, John B. Black Shoe Carrier Admiral: Frank Jack Fletcher at Coral Sea, Midway & Guadalcanal

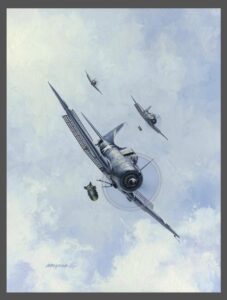

Attack on the Akagi by R.G. Smith

On the anniversary of the Battle of Midway (June 4-5 1942) , Rememberedsky offers some reflection on the battle particularly in context of sea-based airpower given current tension and potential conflict in the South China Sea.

I first read Walter Lord’s well acknowledged book Incredible Victory (1967) while an NROTC midshipmen, and have remained intrigued ever since, even after learning that his major source – the book on the battle by the Japanese air wing commander from Pearl Harbor and present at Midway – was deeply flawed. (See Parshall and Tully Shattered Sword for the story as reflected from the IJN perspective.) It is unquestionably one of the most extraordinary battles in all of history. Even today, eighty -two years after the battle, Midway is much written about and paradoxes and conundrums remain.

The Battle of Midway has been labeled “an incredible victory,” even a miracle. It is considered by many historians as the turning point in the Pacific war, and in summation, the decisive battle in the WW II Pacific. The battle certainly changed the course of the Pacific War in that the loss of the four Japanese carriers turned the tide in the sense that the U.S. could now consider shifting from a defensive and raiding posture to true offensive action. Yet as Japan discovered at Midway, and the U.S. would learn at Guadalcanal the carrier navy still had much to learn in providing air support for an amphibious offensive and how to provide support in defending the landed force while surviving sea-based threats. That role – beyond fighting ships at sea – boded great peril, and greatly complicated how the carriers could and should be used in combat.

And it must be noted post Midway the Japanese Navy (IJN) continued to plan future offensive operations as if they had never lost four carriers, aircrew and significantly, the experienced flight deck operations crewmen. It was only after the Guadalcanal campaign that their operations took on an almost entirely defensive nature.

(The conclusion for me – certainly not the more common thought – the victory at Midway was undeniably crucial in setting the stage, but the true turning point was the hard fought with almost even losses of the Guadalcanal campaign)

But here we are concerned with Midway’s legacy in the context of the battle as a decisive victory?

This post is a modification extracted from my series “1942 – The Year of the Aircraft Carrier,” particularly the 4 part segment on the Battle of Midway. The overall question of decisive battle in light of the war itself is discussed in the Epilogue.

For sake of argument given the overall focus of the series and on possible lessons from this early application of carrier warfare for future air warfare, let’s consider another context – whether beyond the commonly held points of a major turning point or divisive battle of the Pacific War – that the battle was the decisive battle in ushering in a major change in warfare. This post discusses that issue in light of current world issues in which aircraft carriers would play a most significant part.

To begin consider the definition of decisive battles from 100 Decisive Battles From Ancient Times to Present; The World’s Major Battles and How They Shaped History by historian Dr. Paul K. Davis:

- The outcome of the battle brought about a major political or social change – the Norman victory at the Battle of Hastings completely altered the future of the British Isles

- Had the outcome of the battle been reversed. major political or social changes would have ensued – had Washington not crossed the Delaware River or lost at Trenton, the defeat almost certainly would have spelled the end of the American Revolution

- The battle marks the introduction of a major change in warfare (emphasis added)

On this last – major change in warfare – “decisive” then becomes a term worthy of some consideration in regard to combat aviation and the use and validity of carrier aviation, particularly as to what it’s application at the Battle of Midway signifies for today’s application of airpower.

As noted by Thomas Hone, editor of The Battle of Midway; The Naval Institute Guide to the U.S. Navy’s Greatest Victory, … the real nature of the Battle of Midway was poorly understood for some months after the Japanese defeat, indeed initial credit was given to land-based airpower, but this of course was wrong.

The really effective attacks were made by the Dauntless carrier dive bombers. (Art by Wade Meyers from Capt Kevin Miller’s novel The Silver Waterfall)

The validity of carrier-based airpower came two years later on 19- 20 June 1944, in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. You might think of this as “The Battle of Midway, Round Two.” Fought near the island of Saipan in the Marianas group, the Battle of the Philippine Sea set the somewhat rebuilt Japanese carrier force, commanded by Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, against Admiral Spruance’s Fifth Fleet. Both navies had studied the Battle of Midway, and both had learned from it, but it was only the U.S. Navy that had created a carrier force that could advance deep into enemy territory and defeat both land-based and carrier-based air forces. In two days of multiple air battles, the Japanese lost over 90 percent of the aircraft that they had thrown against Spruance’s carriers and surface ships. Philippine Sea was the “last gasp” of the Japanese fleet’s carrier aviators. It is certainly noteworthy that in an effort to compensate for the defeat of its carrier forces and after its defeat at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, at the end of October 1944 the Japanese navy began using kamikaze (suicide) attacks .

Out of World War II in the Pacific, the carrier emerged as THE U.S. capital ship for domination of maritime military operations for 76 years and running. By way of example:

- On 27 June 1950, in response to North Korea’s invasion of South Korea, President Truman ordered naval and air forces to both defend South Korea and deter Communist/Nationalist conflict in Formosa. Valley Forge was the only carrier in the Seventh Fleet and along with the British carrier Triumph formed as Allied Task Force 77 and provided the majority of allied airstrikes on the Korean Peninsula for nearly a month, as the U.S. Air Force worked to establish bases in Korea for tactical aircraft.

- With the escalation of the Vietnam War, developments in aerial tactics allowed smaller, lighter aircraft to deliver large payloads against specific targets. By the end of the war, the U.S. Navy had the ability to fulfill any combat mission that the USAF could, from pinpoint precision strikes to nuclear attack, with the Air Force of course retaining its superiority in B-52 bomber style carpet-bombing.

- During Operation Iraqi Freedom, five carriers were employed in the March 2003 campaign, while two other carriers were in work-ups and two other carriers were on their way to the theater or held in reserve in the Western Pacific.

- In 2014 the Carrier Strike Group (CSG) demonstrated its versatility when the Bush strike group relocated from the Arabian Sea where it had been supporting operations in Afghanistan to 750 NM away in the Arabian Gulf in less than 30 hours and immediately began conducting strikes against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Due to difficulties obtaining basing access and coalition support, the Bush CSG was the only coalition strike force to project air power against ISIS for 54 days.

Since the Battle of Midway, any opponent of the U.S. has had to think and consider how to counter U.S. carrier air power. The Midway battle rightly then can be judged maybe not as the decisive battle of the Pacific war but certainly as deserving of the mantle “decisive” in ushering in such a major long term change in war-at sea.

And yet, despite its mobility, effectiveness and flexibility for crises as a combatant and deterrent, a series of arguments against the Navy’s air arm as a whole and carrier aviation in particular, have persisted throughout the aircraft carrier’s existence. Current anti-access/area denial capability such as China’s DF-21 anti-ship missile highlight current arguments. That A2/AD issue is the basis for most critique on building strategy around CV’s considering the significant cost, high end technology, and people on the newest Ford class CV as seen below, and indeed, what would happen if we lost such a carrier and its 4000 sailors?

USS Ford CVN 78

And thus with all the conundrums and paradoxes from 4 June, 1942 (discussed in the series), there is the lasting paradox brought about by Midway:

- the emergence and continuation of the aircraft carrier as a flexible dominant maritime threat and resource

as compared to - its potential vulnerability and significance of loss.

But despite its vulnerability, one just does not throw away such capability out of fear of loss. What would have been the consequences had admirals King, Nimitz, Fletcher, Spruance, or Halsey given way to that fear?

No matter how you judge the issue of the Pacific War’s turning point, or decisive battle, naval aviation and indeed a total perspective on U.S. airpower, a huge part of that capability follows as legacy from the Battle of Midway.

Selected reading:

-

Complete Series List: 1942- The Year of the Aircraft Carrier by Ed Beakley

-

The Battle of Midway Roundtable edited by Thom Walla

-

Naval History and Heritage Command (Battle of Midway) edited by Admiral Samuel Cox

-

The Silver Waterfall by Kevin Miller

-

Dauntless by Barrett Tillman

-

A Glorious Page in Our History by Barrett Tillman, Mark Horan, Clark Reynolds, et al

-

Incredible Victory by Walter Lord

-

No Right to Win by Ronald W. Russel

-

Shattered Sword by Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully

-

Destined For Glory by Thomas Wildenberg