Testimony of Pilot #34

War and remembrance

War and remembrance

No matter the old, “smart” decision makers

No matter the politics

Or “statecraft” of the DC pundits

It was our war

We fought it

Some lost years

Some lost lives

Some lost family

As young’uns we never set out to buy

but still …

We own it

Band of brothers and sisters

WE SHALL EVER BE

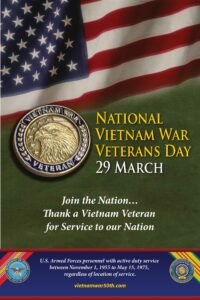

National Vietnam Veterans Memorial Day is today, March 29th, and it is also the 50th Anniversary of this special memorial observance. This is the purpose:

“As we observe the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War, we reflect with solemn reverence upon the valor of a generation that served with honor. We pay tribute to the more than 3 million servicemen and women who left their families to serve bravely, a world away from everything they knew and everyone they loved. From Ia Drang to Khe Sanh, from Hue to Saigon and countless villages in between, they pushed through jungles and rice paddies, heat and monsoon, fighting heroically to protect the ideals we hold dear as Americans. Through more than a decade of combat, over air, land, and sea, these proud Americans upheld the highest traditions of our Armed Forces.

“As a grateful Nation, we honor more than 58,000 patriots—their names etched in black granite—who sacrificed all they had and all they would ever know. We draw inspiration from the heroes who suffered unspeakably as prisoners of war, yet who returned home with their heads held high. We pledge to keep faith with those who were wounded and still carry the scars of war, seen and unseen. With more than 1,600 of our service members still among the missing, we pledge as a Nation to do everything in our power to bring these patriots home.”

Fifty years ago, USS Midway, CAG 5, and the Champs of VA-56 were home. Our POWs Al Nichols and Mike Penn were released on the 28th and 29th. WE had flown the last days of the war in late January. We had lost Gary Shank, Smokey Tolbert and John Lindahl. This site was begun so as to tell the 1972-73 story of the Champs and and CAG 5 – Anthology – RememberedSky Vietnam Air War ’72-’73 Stories .

Conclusions (Excerpts)

Weaver, Michael E.. The Air War in Vietnam (pp. 832-839). Texas Tech University Press. Kindle Edition.

Examining air power effectiveness during the Vietnam War drives one to examine deeper and larger issues. Air power has been put on trial for Rolling Thunder, but it is the wrong defendant. Air operations were only an accessory to an effort comprised of poorly thought-out strategies based on ill-thought assumptions. Assertions that air power failed to win the war in Vietnam flirt with the post hoc ergo propter hoc logical fallacy; Vietnam was not a failure of air power or ground power or a failure of counterinsurgency or conventional warfare, it was a failure of war. Senior leaders never executed the war in a manner the relational complexity of Southeast Asia required.

deeper and larger issues. Air power has been put on trial for Rolling Thunder, but it is the wrong defendant. Air operations were only an accessory to an effort comprised of poorly thought-out strategies based on ill-thought assumptions. Assertions that air power failed to win the war in Vietnam flirt with the post hoc ergo propter hoc logical fallacy; Vietnam was not a failure of air power or ground power or a failure of counterinsurgency or conventional warfare, it was a failure of war. Senior leaders never executed the war in a manner the relational complexity of Southeast Asia required.

American air power was about as successful as it could have been given the character of the war. Even with the problems American air forces had with immature technology, atrophied tactical skills, and limitations in the air picture available to the pilots, air superiority was never really in doubt. It was no surprise they were eminently effective at airlift and air-to-air refueling because of their roots in American logistical practices. Tanker and airlift operations were exercises in logistics and scheduling, so they resided in the middle of America’s managerial strengths. Likewise tactical airlift grew out of a country that always had to move freight and people over continental distances, on ships, railroads, and then through airliners. Photo reconnaissance required a series of processes of flying and photographing. Its shortcoming lay not in completing missions but in realizing at the strategic level how debilitating a problem it was to not be able to easily find the enemy underneath the cover of trees. Close air support was a tactical operation American forces conducted with considerable skill. In general, strike aircraft arrived quickly and bombed accurately. Bad rainstorms, nighttime, and low clouds could ground close air support aircraft, excepting the B-52 and the A-6A—thus the continuing need for artillery.

Operationally, the United States air forces were well organized to fly missions in ways that were reliable, reasonably efficient, and predictable to policy makers.

Other lessons are so rooted in anger they became part of the memory of the war, whether legitimate or not. Earl Tilford and Mark Clodfelter inflicted head shots to the “if only we’d bombed in 1965 like we did in 1972 we’d have won the war in a week” myth three decades ago, only to find that the assertion reanimates itself like a zombie. Similar is the argument that the bombing restrictions lost the war, an assertion seen as so obviously true that no one tests that thesis. It is as if the institutional memory conflates the failure of the war that included an air campaign with a failure of air power—the Vietnam War was not air power’s to win or lose.

American leaders assumed that a form of air warfare that was successful in one context would be equally successful in another. Why wouldn’t bombing a weaker actor in the same manner that was successful against a stronger power work equally well? North Vietnam was weaker than Germany and Japan had been, but it was also far less vulnerable to coercive bombing and interdiction. So-called “strategic bombing”—actually the bombing of factories, refineries, and supply networks—was carried out under the assumption that if one destroys the factories that produce and fuel a mechanized armed force, that army can no longer wage war and will either capitulate or be destroyed. For bombing to hope to bring an enemy to its knees and to the negotiating table, that enemy must have vital centers it cannot live without. Those vital centers did not exist in North Vietnam. North Vietnam had no critical economic infrastructure or factories, and its economy had nothing in common with those of Germany and Japan in World War II.

The vital targets lay in the Soviet Union and China. Rolling Thunder could not function as strategic bombing because there was no finite target set in North Vietnam that, if destroyed, wrecked Hanoi’s strategy, or advanced Washington’s to the point of concluding the war. Certainly the bombing halt of 1968 was an incompetent decision since it took away most of the incentives for the communists to ever negotiate in good faith, and it terminated an attrition campaign that was at least making it more difficult for the communists to wage their war, but broader issues exerted more influence on the effectiveness of military power.

During the Vietnam War, air operations collided with problems that lay beyond the realm of air power, and an examination of air power in the Vietnam War drives us toward larger issues.

Geopolitics disrupted the effectiveness of air power more than did the nature of air power or its machinery. The basic problem lay in the magnitude of the national security threats to the United States, the policy goals the United States set, and the commitment of the Vietnamese Communists to their agenda. One must remember that the Lao Dong Party weaved together extreme nationalism with fanatical communism. They were willing to endure massive death rates over a long period of time in order to unify Vietnam. They were willing to trade the destruction of their own country if in the end they could outlast the persistence of Saigon’s sponsor. For them, the Southeast Asia War was more than a total war, it was existential and almost a religious pursuit. These facts provided them with a foundation of persistence the government in Saigon and especially the Americans likely could not match. In determining whether a war is limited or total, the other side has a vote, and a small regime may in fact be able to stuff the ballot box, if you will, in its favor if its commitment to its cause is exponentially greater than that of the great power it is fighting. In the end, the tie breaker goes to the side willing to suffer and endure more.

The Americans never understood the degree to which the Lao Dong Party devoted itself to absolute and complete victory. Because the members of that political movement were committed to victory at any and all costs, they had more leverage, and the only way South Vietnam and its sponsor could achieve their policy goals was to apply force in a manner and magnitude that permanently prevented the communists from reaching their ambition. Because the North Vietnamese considered the war their highest national priority, the Americans had to respond in kind to have a shot at winning the war and securing the peace thereafter.

But of course the war was never the United States’ greatest national security interest, so the value of the war to the communists gave Hanoi a strategic advantage. They were committed to an unlimited goal, which gave them more staying power and endurance, while the Americans did not really want to fight the war in the first place. They were engaged to preserve a friend of convenience and to protect their credibility with more important allies. The nature of the United States’ purpose for involvement placed a cap on American commitment and endurance that was below that of their enemy.

Americans wanted tactical and operational excellence and weight of effort to overcome impossible geopolitical conditions. Two flawed assumptions surrounded the bomb-the-hell-out-of-them argument: the United States had the ability and the will to bomb North Vietnam sufficiently to persuade the Hanoi government to permanently withdraw its forces back into their own country, and the issue was up for negotiation in Hanoi. The argument replies that if only the Air Force and Navy could have been permitted to destroy every target the JCS could find, of course the North Vietnamese would have sought terms. But Vietnam was a clash of two wills, not target sets, and the Americans badly underestimated the willingness of their enemy to accept hundreds of thousands of bombs and thousands of dead kinsmen in order to outlast their attacker who wished only to win quickly, with the least possible losses, and leave. Not perceiving those relationships was a failure of war.

America’s effort in Southeast Asia was, moreover, a failure of war in that its grand strategy did not adequately meld its elements of power into an application of force that maximized the effects of each.

The most fundamental failure of the war was not the misuse of air power but the lack of a competent understanding of statecraft on the part of the American executive branch. Leaders and advisors did not understand the relationship between diplomacy, national objectives, military force, communicating to the international public, and determination. Halting the bombing of targets in North Vietnam in the belief that that would encourage conclusive negotiations was asinine. Proof of the malpractice of statecraft came when the US attempted that failed tactic over and over after it had not only failed in May 1965, but after the North Vietnamese exploited each bombing pause to gain military advantages.

Since there was a mismatch between the respective forces in terms of policy goals, the United States was going to have to execute a war of limited aims with limited means with exquisite precision and skill, a rare occurrence…, selecting and executing the right strategy and tactics in Vietnam from the beginning and keeping it a war of limited commitment and means was beyond the cognitive capabilities of the United States’ leaders.

It is commonly argued that great powers have the luxury and skill to wage small, limited wars successfully against hostile regimes with a minimum of commitment. Vietnam proved that to be a myth. …. The myth of limited war convinces great powers that they determine when victory or defeat takes place—but the other country has a vote, too. Indeed, in the case of the Vietnam War, the United States could not ultimately determine when victory occurred. It thought it could because of the preponderance of its material power, but in fact the communists were not defeated until and unless they had decided they were defeated.

These wars are neither small nor limited to the countries fighting them. The myth of limited war does not support arguments for a blunt force, unrestricted firepower kind of war in which the civilian leadership turns all aspects of war over to the military.

Expecting an application of limited force to achieve complete success against an uncompromising policy does not add up. Victory for the United States would have required several choices too costly for the country to undertake. The “Wise Men” should have perceived this. …. Achieving the desired outcome requires tools of persuasion that lie far beyond the components of air or ground warfare and requires the United States to blend battlefield events with the realm of governance, and further required the United States to see Vietnam as closer to a total war than a limited war.

An additional failure was the lost opportunity to learn during the war. The pounding North Vietnam was willing to take and the effort it was willing to expend should have made it clear that there was absolutely nothing limited whatsoever about the Hanoi government. Neither presidential administration, Johnson’s especially, ever truly understood what it was dealing with: a regime willing to endure the destruction of its own country in pursuit of conquest. Furthermore, Vietnam was a hybrid of insurgency from within, conquest from without, terrorism, revolutionary activism, guerrilla warfare, and conventional warfare.

The United States understood military operations; it did not understand war as well as it thought it did. Neither administration understood how to measure success. Quants rarely measure policy success in war. If the enemy gives up its fundamental policy objective, you have succeeded in the most important way. Victory was not synonymous with successful operations or tactically effective applications of firepower, important as those are. The enemy’s behavior is the ultimate metric. Victory would come when the United States and South Vietnam convinced their enemies that no matter what they did, they would be worse off tomorrow, and that there is no hope of anything better. The South Vietnamese would have achieved victory when the surviving communist revolutionaries voiced their complaints as a member of the loyal opposition, something beyond the nature of communism. Le Duc Tho observed: “You think military power can make our people submit. I think you are mistaken. Your defeat in Vietnam—where does it lie? Your defeat mainly lies in your wrong assessment of the political forces of our people in standing up against you.”5

Collectively, these failures poisoned the context within which air power expected to function and limited its possibilities for contributing to successfully concluding the war. It is doubtful Rolling Thunder could have ever coerced the North Vietnamese to evacuate their neighbors’ territory, not because of the efficacy of bombing, but because of the monomania of the Communist Party in Hanoi. The overarching concern over escalation and Chinese intervention limited air power’s ability to coerce. The limited commitment to the war led to casualty avoidance and undercut the effectiveness of close air support. Lyndon Johnson’s feckless statecraft produced the bombing halts and prevented air interdiction from having any hope of decisive success. The chronic indeterminate results of air operations, counterinsurgency warfare, and operational strategies were symptoms of a lack of understanding of conflict, war, and peace.

A few authors have made compelling arguments that the Vietnam War was actually a strategic victory for the United States and its Asian friends in the Cold War. Although the United States lost the Vietnam War, it nonetheless achieved important geopolitical goals. … Michael Lind wrote an argument in 1999 I cannot counter that the Vietnam War, while a loss for the United States, was a strategic victory in the Cold War.9 Most recently, Wen-Qing Ngoei assessed the Vietnam War as a successful containment of Chinese and Soviet expansionism that supported the agendas of regimes from Manila to Jakarta.10

But what a costly victory.

Notes

- History Naval Operations, Vol. III 1965–1967, Part 1, 103, Vietnam Command Files, COLL/372, Box 85, File CNO NHO, Vol. III, Part 1, NHHC; Van Staaveren, Gradual Failure, 263–65.

- Conversation between President Nixon and Richard T. Kennedy of the National Security Council Staff, December 27, 1972, FRUS IX, 1969–1976, 840–41.

- John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of Postwar American National Security (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 298; Prados, The Blood Road, 363.

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. and ed. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 80.

- Memorandum of Conversation, April 4, 1970, FRUS 1969–1970, VI,

- Colvin, “Hanoi in My Time,”

- Palmer, The 25-Year War, 173.

- Warren Bell, et al., “Reporting the Darkness: The Role of the Press in the Vietnam War,” David L. Anderson, Facing My Lai: Moving Beyond the Massacre (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998), 72.

- Michael Lind, Vietnam, the Necessary War: A Reinterpretation of America’s Most Disastrous Military Conflict (New York: Free Press, 1999).

- Wen-Qing Ngoei, Arc of Containment: Britain, the United States, and Anticommunism in Southeast Asia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), 149–50, 176.