Blown Slick Series #13

Seventy-five years ago -1943 – Nimitz, King, and particularly the air navy admirals worked a seemingly endless slate of problems to leverage the advantages the navy had hard earned in the last year. The F-4 Wildcat was replaced with new F-4U Corsairs and F-6F Hellcats. Scout bombers and torpedo bombers were replaced but the Dauntless replacement proved problematic. Roles and missions had to be adjusted, particularly for the ever increasing demands of observation and reconnaissance. New Essex class aircraft carriers were coming on line. The careful days of a single carrier in the Pacific after Guadalcanal were over, but how best to employ – individually or with possibly more CVs inside the screen? Experienced carrier operators supported both concepts.

In addition, the fight over who’s in charge between Admiral Nimitz and General MacArthur was constant, but it had serious repercussions. MacArthur wanted Navy carriers to protect his right flank as he moved northward with Army Air Force fighters and bombers executing the main thrust from the air. But the Army approach would place the carriers in restricted island waters most vulnerable to Japanese land-based air, and second the Army Air Force and Navy differed drastically in the approach of air support for troops – a major concern for the Navy/Marine Corps combination of fast carriers and amphibious operations intended for the thrust in the central Pacific. Much was at stake and all of it allowed by the hard won battles and lessons of 1942.

Today the context is what to do with A-10’s for Close Air Support (CAS), a new carrier with problems, an expensive over due multi-role 5th generation F-35 with three service variants, and two very different types of war to consider – the insurgencies of the Middle East and the more conventional potential conflicts with Russia and China. Conventional. yes, but threat technologies like S-400 SAMs and their own versions of 5th generation create much concern. China is of particular interest for the Navy because of the islands and waterways associated with the South China Sea.

Based on China’s rapidly developing A2/AD or anti-access/area-denial capabilities focused on a “two island chain” defense perimeter for the South China Sea (and also Iran’s similar albeit far more modest capabilities, focused on the Persian Gulf) in September 2009 the US Air Force chief of staff, General Norton Schwartz, and the US Navy’s chief of naval operations, Admiral Gary Roughead, signed a classified memorandum to initiate an effort by their Services to develop a new operational concept known as “AirSea Battle.”

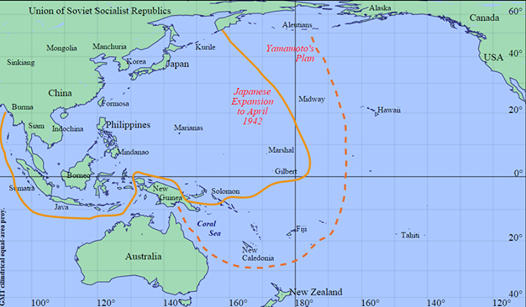

A notional operational concept (developed by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, CBSA) centered around future power projection was presented for review in the spring of 2010 to mixed reviews. Some seemed to think the authors were attempting to regenerate a 21st Century Battle of Midway. Yet in at least some ways the Chinese two island chain defense of the South China Sea is not so different from the Japanese approach related to attacking Pearl Harbor and Midway which sought to eliminate the United States as a strategic power in the Pacific, thereby giving Japan a free hand in establishing its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

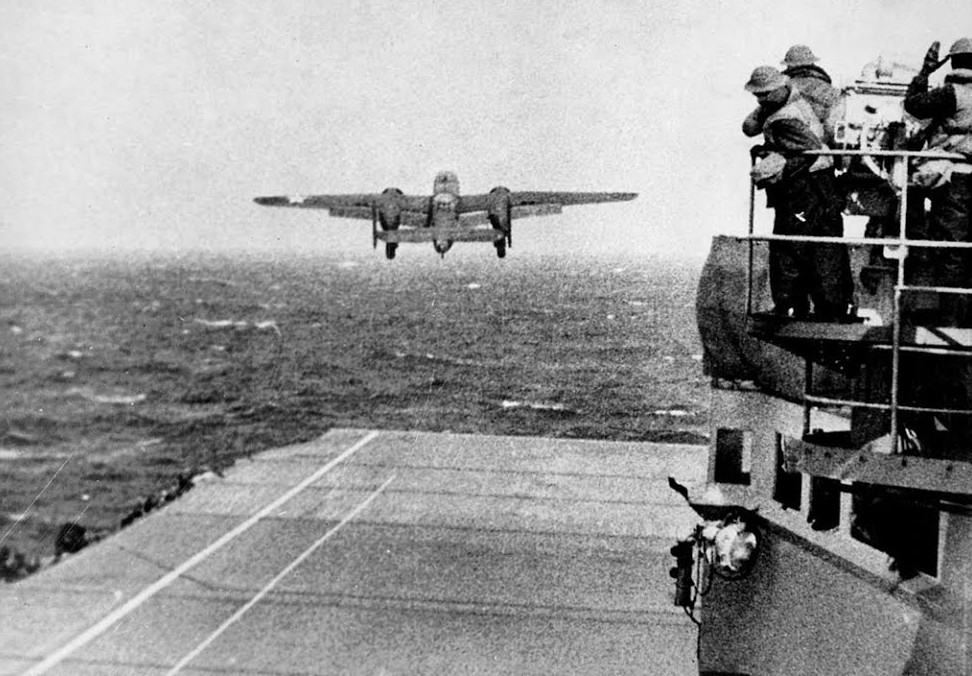

Indeed, any assessment of future air power must certainly take into account China’s growing defense capability, objectives, and ongoing operations, so a reasonable starting point suggested is a review of that first year of WW II in the Pacific and the emergence of aircraft carrier warfare. On its 18 April, 1942 anniversary we start with the Doolittle Raid from USS Hornet in Part 2. Follow-on pieces will then provide a review of the four major carrier battles throughout 1942.

Overview: 1942, the Year of the Carrier

On 18 April, 1942, sixteen B-25B Mitchell medium bombers were launched without fighter escort from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) deep in the Western Pacific Ocean. The plan called for them to bomb military targets in Japan, and to continue westward to land in China. The raid caused negligible material damage to Japan, but it achieved its goal of raising American morale and casting doubt in Japan on the ability of its military leaders to defend their home islands. Prior to Doolittle’s Raid, the senior Japanese Army officers had strongly opposed the attack on Midway. After the attack they felt compelled to support a response and therefore turned to support and thus the raid contributed to Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s decision to attack Midway Island —an attack that turned into a decisive strategic defeat of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) by the U.S. Navy in the Battle of Midway

The severe Japanese losses in carriers at Midway prevented the Japanese from reattempting to invade Port Moresby from the ocean and helped prompt their ill-fated land offensive over the Kokoda trail. Two months later, the Allies took advantage of Japan’s resulting strategic vulnerability in the South Pacific and launched the Guadalcanal Campaign; this, along with the New Guinea Campaign, eventually broke Japanese defenses in the South Pacific and was a significant contributing factor to Japan’s ultimate surrender in World War II.

While the Battle of Midway was a crushing defeat of the Imperial Japanese Navy, that battle did not stop Japanese offensives, which continued both at sea and on the ground. The victories at Milne Bay, Buna–Gona, and Guadalcanal marked the Allied transition from defensive operations to the strategic initiative in the theater, leading to offensive campaigns in the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, and the Central Pacific, that eventually resulted in the Surrender of Japan and the end of World War II.