Blown Slick Series #13 Part 21

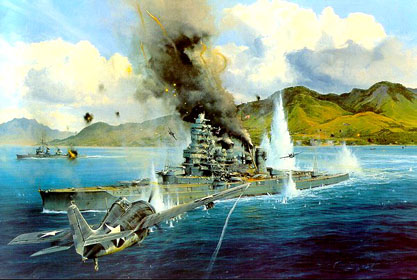

On the morning of 13 November 1942, Marine aircraft of the “Cactus Air Force” attacked and caused the destruction of the Japanese battleship Hiei off Savo Island. F4F Wildcat fighters of Marine squadron VMF-121, commanded by Captain Joe Foss, are engaged in a diversionary attack on the battleship to cover an attack by Avenger torpedo bombers of Marine squadron VMSB-131. By Robert Taylor.

As the end of this series approaches please note that the year of the carrier is not intended to address the overall war in the Pacific nor all aspects of the Guadalcanal Campaign which included significant land and sea battles in addition to the two carrier vs. carrier battles. While the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands was the last of four carrier battles in 1942, the series would not be complete without some discussion of the actions of the Cactus Air Force and USS Enterprise/Air Group Ten during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal fought November 12-15, 1942.

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

This battle is addressed by most historians/authors in two parts – the night surface battles of 12-13 Nov and then that of 14-15 Nov 1942. Given the complexity, close range fire exchanges, the loss of two U.S. admirals and one of only two battleship engagements in WW II, that characterization is well founded. But that focus tends to under explain the actions of the Cactus Air Force and Air Group 10 on USS Enterprise. For purpose of this series, the 12-15 November battle is divided into 6 engagements so as to place the contribution of both land and sea based airpower into proper context with the night surface battles.

Engagement 1: Night of 12-13 Nov (beginning of Part 1, the first night surface battle)

Despite their failures to land more troops on Guadalcanal as part of The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, the Japanese continued their efforts to capture Henderson Field and force U.S. withdrawal from Guadalcanal. Still unable to move reinforcements to the island during daylight hours due to the threat posed by mostly air attacks by the Cactus Ar Force, they were limited to delivering troops at night using destroyers. These ships were fast enough to steam down “The Slot” (New George Sound), unload, and escape before Allied aircraft returned at dawn. This method of troop movement, dubbed the “Tokyo Express”, proved effective but precluded the delivery of heavy equipment and weapons. Additionally, Japanese warships would use the darkness to conduct bombardment missions against Henderson Field in attempts to hinder its operations.

Admiral Yamamoto, prepared for a large reinforcement mission to the island with the goal of putting up to 7,000 men ashore along with their heavy equipment. Organizing two groups, he formed a convoy of 11 slow transports and 12 destroyers under Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka and a bombardment force under Vice Admiral Hiroaki Abe. Consisting of the battleships Hiei and Kirishima, the light cruiser Nagara, and 11 destroyers, Abe’s group was tasked with bombarding Henderson Field to prevent Cactus aircraft from attacking Tanaka’s transports. With a new break in intercepting and deciphering Japanese messages, Admiral Halsey dispatched a reinforcement surface ship force (Task Force 67) into the straights around Savo Island and Guadalcanal.

To protect the supply ships, Rear Admirals Daniel J. Callaghan and Norman Scott were dispatched with two heavy cruisers three light cruisers, as well as 8 destroyers. Nearing Guadalcanal on the night of November 12/13, Abe’s formation became confused after passing through a rain squall. Alerted to the Japanese approach, Callahan formed for battle and attempted to cross the Japanese T. After receiving incomplete information, Callahan basically ignored his radar capability and issued several confusing orders from his flagship (San Francisco) causing his formation to come apart. As a result, the Allied and Japanese ships became intermingled at close range.

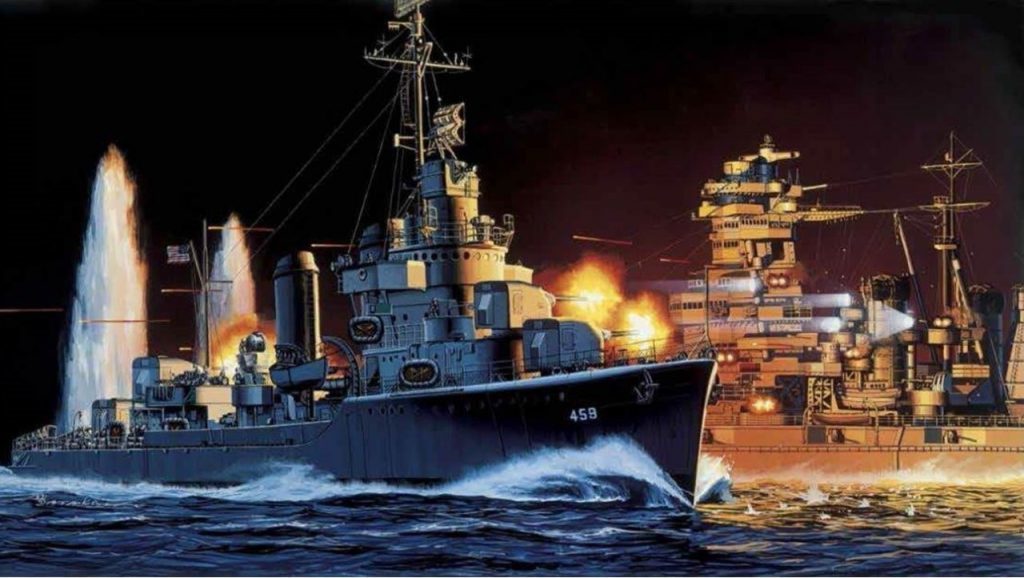

Navy Art Collection painting depicting destroyer Laffey just after she has crossed under the Japanese battleship Hiei’s bow and is engaging the battleship with 5-inch and 20-mm guns—and sidearms—at near-point-blank range.

At 1:48 AM, Abe ordered his flagship, Hiei, and a destroyer to turn on their searchlights. Illuminating the cruiser Atlanta, both sides opened fire. Realizing that his ships were nearly surrounded, Callahan ordered, “Odd ships fire to starboard, even ships fire to port.” In the naval melee that ensued, Atlanta was put out of action and Admiral Scott killed. Fully illuminated, Hiei was mercilessly attacked by US ships which wounded Abe, killed his chief of staff, and knocked the battleship out of the fight.

But while taking fire, Hiei and several Japanese ships pummeled cruiser San Francisco, killing Admiral Callahan, forcing the cruiser to retreat. After 40 minutes of fighting, Abe, perhaps not knowing he had achieved a tactical victory and that the way to Henderson Field was open, ordered his ships to withdraw.

Engagement 2: Day of 13 Nov (end of Part 1, air attacks on the Hiei)

During the morning and early afternoon, IJN carrier Junyo located about 200 miles north of the Solomons dispatched several combat air patrols, consisting of fighters and bombers to cover the crippled Hiei. In addition, several more patrols were dispatched from ground bases at Rabaul and Buin. These aircraft were routinely shotdown or driven off by Marine F4F Wildcats from Henderson Field. (Picture above)

At 0810 concerned with effective operations due to the damage to her forward flight deck elevator (Battle of Santa Cruz), Admiral Kinkaid on Enterprise sent nine TBFs and six F4Fs from her Air Group 10 to lower the number of planes on her deck. This substantially reinforced the Cactus Air Force at Henderson Field and proved to provide much better flexibility for total air operations over the course of the coming engagements.

Despite engagements with the Japanese air patrols, Hiei was attacked repeatedly by Marine TBF Avenger torpedo planes from Henderson Field, Navy TBFs and SBD Dauntless dive-bombers from Enterprise, plus B-17 Flying Fortress bombers of the Army Air Forces’ 11th Bombardment Group from Espiritu Santo. Abe and his staff were forced to transfer to Yukikaze at 08:15. An attempt to tow was cancelled because of the threat of submarine attack and Hiei’s increasing unseaworthiness. After sustaining more damage from air attacks, the battleship sank northwest of Savo Island in the late evening of 13 November.

In the fighting, U.S forces lost two light cruisers and four destroyers, as well as had two heavy and two light cruisers damaged. IJN losses included Hiei and two destroyers.

This action stands without peer for furious, close range, and confused fighting during the war. But the result was not decisive. The self-sacrifice of Callaghan and his task force had purchased one night’s respite for Henderson Field. It had postponed, not stopped the landing of major Japanese reinforcements, nor had the greater portion of the (IJN) Combined Fleet yet been heard from. Richard Frank

Engagement 3: Night of 13-14 Nov (beginning of Part 2, bombardment of Henderson Field)

Despite, Abe’s failure, Yamamoto elected to proceed with sending Tanaka’s transports to Guadalcanal on November 13. To provide cover, he ordered the 8th Fleet’s Cruiser Force (4 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers) to bombard Henderson Field. A little after 2 AM of the 14th Japanese cruisers and destroyers initiated the bombardment of the airfield destroying one SBD-3 and two F4F-4s with seventeen F4F-4s damaged, but with minimal damage to the airfield itself.

At 0340 six PT boats from Tulagi attacked the Japanese ships with torpedoes inflicting no significant damage done. Still, the Japanese halted their bombardment and retired to the northwest around New Georgia.

Engagement 4: Day of 14 Nov (Part 2, air attacks on the Japanese transports)

At day break on the 14th aircraft from Henderson Field, Espiritu Santo, and Enterprise—stationed 200 nmi south of Guadalcanal—began attacks, first on the retreating force heading away from Guadalcanal, and then on the transport force heading towards the island. Repeated air attacks on the transport force overwhelmed the escorting Japanese fighter aircraft, sank six of the transports including Kinugasa, killing 511 of her crew, and forced one more to turn back with heavy damage (it later sank). As example of the engagements:

At dawn had Enterprise sailed through squalls, low clouds and rain. Kinkaid launched ten SBD Dauntless dive bombers and at 9:15 a.m., Lt. j.g. Robert D. Gibson reported contact with enemy ships–two battleships and two cruisers. Gibson had actually found Mikawa’s cruisers and destroyers. Shadowing them for an hour, he then swooped in at 9:30 on the heavy cruiser Kinugasa, dropping 500-pound bombs at 1,000 feet. The bombs hit the front of Kinugasa‘s bridge, killing the ship’s captain and the executive officer and blowing holes in the ship’s plating. The veteran cruiser quickly acquired a 10-degree port list. Soon after, other dive bombers arrived and attacked Maya.

Seventeen more Dauntlesses came overhead at 10:45. Their attacks left cruiser Chokai‘s boiler room flooded, the light cruiser Isuzu lost her steering, and near-misses knocked out Kinugasa‘s engines and rudder, opening more compartments to the sea. Kinugasa capsized at 11:22 with 511 of her crew.

Meanwhile, Rear Adm. Raizo Tanaka’s 23-ship convoy headed south and were attacked by planes from Enterprise but with no hits. In a noon attack a strike force of Enterprise torpedo bombers and Marine dive bombers from Cactus sank two transports and a third was sent home badly damaged.

All afternoon the Americans continued to pound the convoy with Marine dive bombers, Enterprise planes and B-17 Flying Fortresses. The Flying Fortresses shoved aside intercepting Japanese Zero fighters, whose guns were too light to penetrate the American planes’ tough hides. Those contingents started a fire that sank Brisbane Maru.

Next, at 3:30, came dive bombers from Enterprise under Lt. Cdr. Jimmy Flatley. They crippled two freighters, which had to be abandoned, then headed for Guadalcanal. Enterprise herself turned southward. She had more than done her job.

That afternoon aircraft from Enterprise and Marine planes, both based on Henderson Field, hit the convoy, sinking Nako Maru. Zeroes shot down three dive bombers during the attack, Some 13 Zeroes were felled.

All day long the battle raged, creating fantastic scenes–skies full of flak bursts, destroyers spewing smoke screens to cover freighters, transports exploding from bomb hits. By dusk, most of Tanaka’s freighters were burning or had been sunk, and his destroyers were stuffed with troops. Six Japanese transports had been sunk or abandoned, and only nine of 23 transports were still in convoy. Japanese losses had amounted to 450 men.

Survivors from the transports were rescued by the convoy’s escorting destroyers and returned to the Shortlands. The remaining four transports and four destroyers continued towards Guadalcanal after nightfall of 14 November, but stopped west of Guadalcanal to await the outcome of a warship surface action developing nearby (see below) before continuing. To support them, Admiral Nobutake Kondo arrived with battleship Kirishima, 2 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, and 8 destroyers.

Engagement 5 (The second night battle – Part 2)

Having taken heavy casualties on the 13th, Halsey detached the battleships USS Washington (BB-56) and USS South Dakota (BB-57) as well as 4 destroyers from Enterprise’s (CV-6) screening force designated as Task Force 64 under Rear Admiral Willis Lee. Moving to defend Henderson Field and block Kondo’s advance, Lee arrived off Savo Island and Guadalcanal on the evening of November 14.

Approaching Savo, Admiral Kondo dispatched a light cruiser and two destroyers to scout ahead. At 10:55 PM, Lee spotted Kondo on radar and at 11:17 PM opened fire on the Japanese scouts. This had little effect and Kondo sent forward Nagara with four destroyers. Attacking the American destroyers, this force sank two and crippled the others. Believing he had won the battle, Kondo pressed forward unaware of Lee’s battleships. While Washington quickly sank the destroyer Ayanami, illuminated by searchlights, South Dakota received the brunt of Kondo’s attack, and eventually began to experience a series of electrical problems which limited its ability to fight.

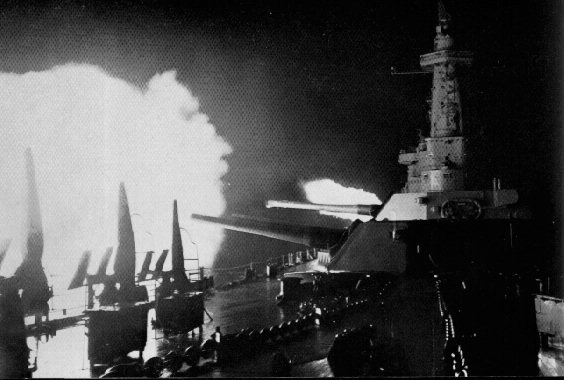

Meanwhile, Washington stalked the battleship Kirishima before opening fire with devastating effect.

Battleship USS Washington firing her main battery at the Japanese battleship Kirishima

Hit by over 50 shells, Kirishima was crippled and later sank. A little after midnight Admiral Kondo ordered withdrawal of IJN ships, abandoning his bombardment plan.

In summary, the second night battle was a clear cut u.s. victory led by Admiral Lee on the Wisconsin. Lee was an expert in the use of radar which definitely offset the Japanese continually demonstrated capabilities in night surface warfare. Noted by Frank “unlike Callaghan, Lee never allowed the action to degenerate into a nautical brawl, because he formulated a workable plan and then adhered to it…”

Lee himself stated “We… realized then and it should not be forgotten now, that our entire superiority was due almost entirely to our possession of radar. Certainly we have no edge on the Japs in experience, skill, training, or performance of personnel.”

Engagement 6: Day 15 Nov ( Aftermath- Part 2, air attacks on the beached IJN transports)

The four Japanese transports beached themselves as ordered at Tassafaronga on Guadalcanal by 04:00 on 15 November, and Tanaka and the escort destroyers departed and raced back up the Slot toward safer waters. The transports were attacked, beginning at 05:55, by U.S. aircraft from Henderson Field and Enterprise, and by field artillery from U.S. ground forces on Guadalcanal.

Beached Japanese transports after air attacks

Later, destroyer Meade approached and opened fire on the beached transports and surrounding area setting even more fires on the transports and destroying any equipment on them that the Japanese had not yet managed to unload. Only 2,000 to 3,000 of the embarked troops made it to Guadalcanal, and most of their ammunition and food were lost.

Endgame

The Allied success in the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal ensured that the Japanese would be unable to launch another offensive against Henderson Field. Thus, the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was the last major attempt by the Japanese to seize control of the seas around Guadalcanal or to retake the island. Final thoughts on the Guadalcanal Campaign continue in Part 22.

Note: Both night battles were extremely intense and violent. Given the basic top level overview approach here, readers are encouraged to investigate further in the references provided in the next article – Endgame.