Blown Slick Series #13 Part 20 (2/2)

Who won? As the two navies carrier battle groups retreated from the fourth and last carrier battle of 1942, the Japanese by multiple metrics could be judged to have won the day. Both sides were damaged greatly in similar manner, but for the Japanese, in a singular way that would be unrecoverable and thereby fatal when next Japanese and American carriers dueled – their experienced squadron and section leadership was decimated.

What Price Victory?

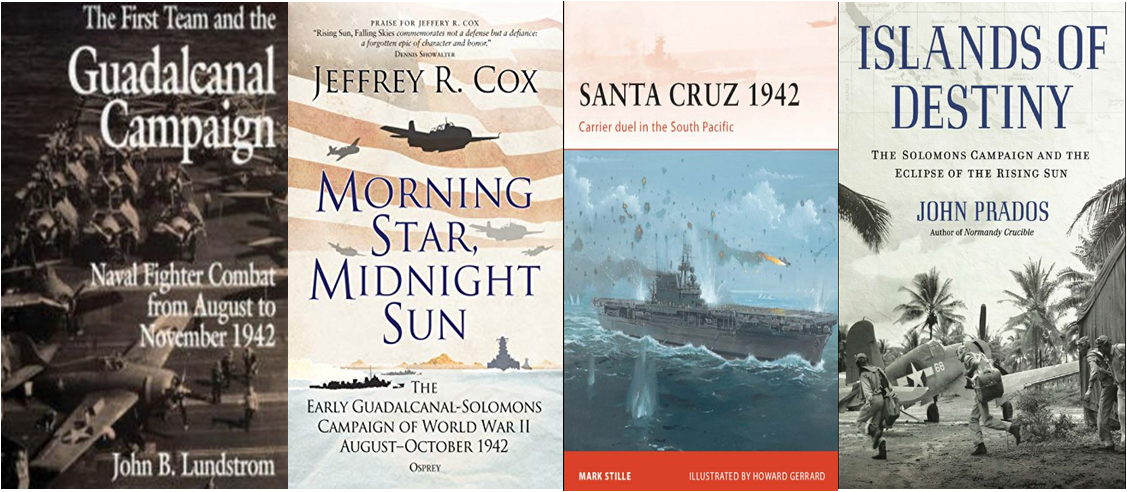

American observers take a variety of positions on the outcome at Santa Cruz. Marine General Vandegrift termed the battle a “standoff.” Theater commander Admiral “Bull” Halsey wrote that “tactically, we picked up the dirty end of the stick but strategically we handed it back.” Similarly, official Navy historian Samuel Eliot Morison rated the battle a Japanese tactical victory that gained precious time for the Allies. And aviation historian John Lundstrom, author of the most detailed examination of the aerial exchanges, wrote of a “supposed” Japanese decisive victory. Robert Sherrod, chronicler of Marine aviation in the war, said Santa Cruz was a case in which “the box score is deceptive.”

By many reasonable measures the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands marked a tactical Japanese victory—and possibly a strategic one. The Imperial Japanese Navy had pursued Kinkaid’s retiring fleet, indeed forced it away from the battle zone. The sinking of a U.S. fleet carrier, the Hornet , was a notable achievement. The day after the action, the Japanese possessed the only operational carrier force in the Pacific. In addition to having sunk more ships—of greater combat tonnage—the Japanese had more aircraft remaining and were in physical possession of the seas. Only the escape of the Enterprise with her own and most of the Hornet’s aircraft prevented disaster. Yet the Allies retained the strategic advantage because of the 17th Army’s failure to capture the Lunga airfield and destroy the 1st MarDiv on Guadalcanal, and in consolation TF-61 also savaged the Japanese carrier air groups.

Admiral Yamamoto and the Combined Fleet would fail to exploit the success at Santa Cruz, but the fact that the naval effort later went sideways cannot diminish the Imperial Japanese Navy’s achievement on 26 October 1942.

While the battle ended in an American tactical defeat, it is necessary to look not only at the respective claims but also the nature of the end game statistics of the two navies for the Santa Cruz battle, particularly as neither side had any real notion of the strength of the other. Imperial General Headquarters and Combined Fleet consistently overestimated the numbers of their foe, deciding that four enemy carriers fought the battle and that all four sank, along with two battleships. That put the total carriers sunk since the outbreak of the war as eleven, with four others damaged. (Obviously the Americans must have had a lot of carriers.) But simple statistics reveal the grievous wounds suffered by the four Japanese carrier air groups.

Though the losses of aircraft were about equal—ninety-seven Japanese planes were lost against eighty-one U.S.—it was in personnel casualties that America gained a most striking if seldom-appreciated strategic victory. Despite good use of dive bombers and Torpedo carrier attack aircraft this was Japan’s first concentrated exposure to state-of-the-art antiaircraft fire; 148 pilots and aircrew died—a third more than at Midway (110). Fully half of Nagumo’s dive-bomber flight crews were lost while American squadrons suffered twenty dead on the day, plus four more rescued by the enemy and taken prisoner. The leadership in the IJN’s squadron ready rooms took a severe blow; twenty-three squadron and section leaders were lost. By sundown that day, more than half of the pilots who had hit Pearl Harbor on December 7 had been killed in action. The carriers Zuikaku and Junyo, though not seriously damaged, were forced home to Japan for want of men to fly their planes.

Note,the IJN decision to return the Zuikaku to Japanese Empire waters was entirely voluntary, based on a plan to regenerate for another Guadalcanal offensive timed for January 1943. She could have been retained in the South Pacific.

With the evisceration of its naval aircrews, the Japanese suffered a critical deficit that they would never make up. An IJN Captain’s assessment was a profound understatement: “Considering the great superiority of our enemy’s industrial capacity, we must win every battle overwhelmingly. This last one, unfortunately, was not an overwhelming victory.”

The caliber of experience and leadership could not easily be replaced. Even with the disparity in numbers, Yamamoto became extremely cautious with deployment of his carriers. In this regard the “Naval Battle of the South Pacific” truly became a Pyrrhic victory for Japan.

As such, after the Battle of Santa Cruz, the United States would have not a single operable carrier task force in the South Pacific until the Enterprise could be repaired at Nouméa and placed back into service. Task Force 17 was dissolved with the sinking of the Hornet. And with the Enterprise going to the yard for repairs, the battleship South Dakota was sent to join the Washington in Task Force 64.

At battle’s end, although the Big E could launch and recover aircraft, she was not truly combat-ready and in a renewed engagement would have been gravely disadvantaged. Battle speeds and even stormy seas might have threatened her seaworthiness. Damage-control parties—plus every spare hand—bent superhuman efforts to enable the ship to make speed despite her damage. Some repairs could only be made in port.

The combination of bomb hits and near misses that Enterprise sustained at Santa Cruz did more than jam one elevator in place on her flight deck, thereby slowing flight operations. Two near misses had sprung rivets or deflected plates—in places as much as 2½ feet inward—opening fuel tanks to the sea along almost 100 feet of hull. In one area, all the frames, floors, and bulkheads had buckled. Leaks threatened. The Enterprise’s stem was laced with fragment holes, a few up to a foot wide, and she was taking water, down four feet by the bow. On the hangar deck, the floor of a 50-foot section near the No. 1 elevator was heavily damaged, the decks below blown out. Two bomb hoists were questionable. The bridge gyroscope had failed. Several radios and a direction-finding loop were out.

For 11 days after the carrier arrived at Nouméa she was completely incapacitated, as Admiral Halsey added every engineer and repairman to those already working over the ship. Hull breaches were repaired, but the aircraft elevator jam awaited dry docking in the United States. When the Enterprise went to sea again, Pearl Harbor privately estimated that the carrier was operating at 70 percent of her combat efficiency.

Having exhausted their carrier forces in the seas east of Guadalcanal on October 26, the opposing fleets obviously needed to regroup. With differing context, Halsey’s and Yamamoto’s carriers were both sidelined for now. The question to be answered in the continuing contest for Guadalcanal in the coming weeks was: Which side’s surface combat fleet would step up and control the seas by night? No matter how gallantly men might fight on land, they would not hold on long if their Navy finally failed them. In a few short weeks, the greatest challenge yet to the American position on Guadalcanal would loom in the dark waters of Savo Sound.

The only feasible way the Japanese had to deprive their enemy of air superiority was to destroy Henderson Field’s air group with bombardment from the sea. And by that same reasoning, the only way the Americans could prevent a repeat of the devastating nighttime ordeal of mid-October was by pressing their surface forces into the fight and seizing control of the night. The wartime “food chain” circled right back to the ancient art of ships grappling with one another on the sea.

Halsey was painfully aware that flight operations from his only carrier, the Enterprise, without the use of her forward elevator until near the end of the November, would be significantly constrained Nonetheless, he knew that whatever airpower she could throw into the coming fight would be indispensable. Accordingly, on the morning of November 11, Halsey ordered the Enterprise task force to sea and to operate north from Nouméa with instructions to take positions two hundred miles south of San Cristobál and strike Japanese shipping near Guadalcanal.

The two night November destroyer, cruiser, battleship engagements comprising The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal were eminent. Cactus Air Force and Enterprise pilots must play their role.

The next carrier vs carrier battle would not be until June 1944 at the Battle of the Philippine Sea – the “Mariana’s Turkey Shoot.“

******************