Blown Slick Series #13 Part 19 (1/2)

On the morning of 26 October, during the attack on the Enterprise, Task Force 61 Commander Admial Thomas Kinkaid remarked with pardonable hyperbole to AP correspondent Eugene Burns: “You’re seeing the greatest carrier duel of history. Perhaps it will never happen again.”

John Hamilton’s depiction of fighting around the battleship South Dakota and carrier Enterprise during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands.

We come now to the fourth and final carrier battle of 1942, what the Japaneses referred to as the Battle of the South Pacific. Yet despite the task force commander’s comment above, the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands is arguably either the forgotten or least noted of the carrier battles of that year or at best remembered as the battle where the USS Hornet was sunk and a Japanese victory. But, the Japanese “victory” was Pyrrhic. The true mark of the Battle of the Santa Cruz is that Japanese losses were so grievous that they withdrew from significant carrier participation, not to return until the the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944 – the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.

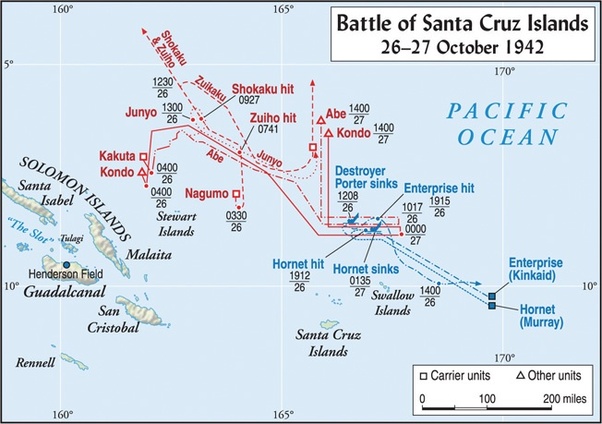

The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, [25–27 October 1942] was the fourth carrier battle of the Pacific campaign and was the fourth major naval engagement fought during the Guadalcanal campaign.

The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

After the 7 August invasion of Guadalcanal and stand-up of Henderson Field, Admiral Yamamoto’s original counter was primarily to destroy the U.S. fleet including U.S. carriers but with an obvious but parallel goal to retake the island utilizing ground forces, land based air, and bombardment by surface forces.

Despite major attempts, the U.S. hold on Guadalcanal, while tenuous, still held and the marginal American victory at the carrier Battle of the Eastern Solomons thwarted a major Japanese insert of ground forces. Even with the gift by his submarine forces of a damaged and sent home USS Saratoga and sinking of the USS Wasp in September, Admiral Yamamoto determined to change his concept of operations from first destroying the American fleet to supporting the land offensive to seize Henderson Field using a combined sea and air operation to neutralize the airfield This would allow a greater number of ground forces to be landed to seize the airfield successfully. With that accomplished, the Combined Fleet would close on Guadalcanal to destroy the American fleet as it rushed to the aid of the Marines.

Japanese insert of ground forces. Even with the gift by his submarine forces of a damaged and sent home USS Saratoga and sinking of the USS Wasp in September, Admiral Yamamoto determined to change his concept of operations from first destroying the American fleet to supporting the land offensive to seize Henderson Field using a combined sea and air operation to neutralize the airfield This would allow a greater number of ground forces to be landed to seize the airfield successfully. With that accomplished, the Combined Fleet would close on Guadalcanal to destroy the American fleet as it rushed to the aid of the Marines.

************************

The battle of the 26th had many elements, far too many for complete discussion here and so the reader is encouraged to explore the sources provided at the end. Below, this post will provide some of the battle highlights and then analysis will be provided in a second post. The intertwining of the Japanese and American efforts with resultant complexity of the battle can readily be seen in the following abbreviated timeline:

-

- October 11- Japanese Combined Fleet departs Truk to support Guadalcanal offensive.

- October 11 (night) – The Battle of Cape Esperance – American task force intercepts the Japanese cruiser force tasked to bombard the Henderson Field. The resulting engagement was the first American victory in a night battle during the campaign.

- October 13–14 Two Japanese battleships bombard and temporarily neutralize Henderson Field.

- October 14–15 Japanese reinforcement convoy arrives on Guadalcanal.

- October 24–25 The Battle of Henderson Field Japanese ground attack fails.

- October 25 Japanese and American carriers maneuver without engagement

October 26

-

- 0250 – American PBY attacks Nagumo’s carrier force.

- 0612 – Japanese aircraft spots TF-61. Report does not reach Nagumo till 0658

- 0645 – Enterprise aircraft spots Japanese carriers.

- 0710 – Japanese launch multi-carrier strike against TF-61.

- 0732 – Hornet launches strike.

- 0740– Enterprise scout Dauntlesses bomb light carrier Zuiho taking her out of the battle

- 0747 – Enterprise launches strike.

- 0818 – Shokaku’s second wave departs followed by Zuikaku’s second wave at 0900

- 0910 – Japanese dive-bombing attack begins on Hornet; three hits scored.

- 0914 – Japanese dive-bomber crashes into Hornet followed by two torpedo hits and a second Japanese aircraft crash into Hornet.

- 0926 – Hornet Dauntlesses attack heavy cruiser Chikuma and score two bomb hits while Hornet Dauntlesses score four to six bomb hits on carrier Shokaku.

- 0930 – Enterprise Avengers attack heavy cruiser Suzuya followed by Enterprise Dauntlesses attack on Chikuma.

- 1017 – First of two bomb hits on Enterprise from Japanese second wave dive-bombing attack

- 1046 – Japanese torpedo attack on Enterprise; no hits are scored.

- 1121 – Junyo dive-bomber attack against Enterprise scores one near miss.

- 1129 – Junyo dive-bombers attack battleship South Dakota and score one hit followed by one hit on cruiser San Juan;

- 1135 – Kinkaid informs Halsey of his decision to break off engagement.

- 1513 –1650 Japanese continue attack on Hornet;

- 2100 – Japanese destroyers torpedo already burning Hornet; the carrier sinks early the next morning.

- 2300 – Kondo breaks off pursuit of the retreating Americans.

************************

Yamamoto intensified land-based air attacks on Henderson Field with two-a-day attacks beginning on October 11. But late on the night of October 11, an American task force intercepted the Japanese cruiser force tasked to bombard the airfield. The resulting engagement, known as the Battle of Cape Esperance, was the first American victory in a night battle during the campaign. The Japanese lost a heavy cruiser and a destroyer sunk, but the reinforcement group did complete its mission.

Subsequently, on the night of 13/14 October, two Japanese battleships arrived off Guadalcanal, completely by surprise, and fired almost 1,000 14-inch shells into Henderson Field in the most devastating battleship bombardment experienced by any ground troops up to that point in history

More than half the aircraft at Henderson Field were destroyed and many of the rest were damaged to various degrees, and most stores of aviation fuel were destroyed. Although 24 of 42 Wildcats were flyable, only 7 of 39 SBD dive bombers and none of the six TBF torpedo bombers were airworthy.

Destroyed aircraft at Henderson Field.

As a result, when Vice Admiral William F. “Bill” Halsey, arrived at Noumea on 18 October expecting to take over command of the carrier task force TF-61, he was instead ordered By Admiral Nimitz to relieve Admiral Ghormely as Commander of the South Pacific Area.

After multiple delays, the Japanese 17th Army began their planned ground attack focused on Henderson Field. The battle known as the Battle for Henderson Field took place from 23 to 26 October and was the third of the three major land offensives conducted by the Japanese during the Guadalcanal campaign. The attack was chaotic and was defeated piecemeal by the Marines. It was the last serious ground offensive conducted by Japanese forces on Guadalcanal.

Of note in the confusion of battle, at 0130 on October 25, the army attackers passed the word to Yamamoto that the airfield had been taken. In fact, the airfield remained in American hands. Throughout the day, the Japanese attempted to keep fighters over Henderson Field, including a late afternoon strike by 12 fighters and 12 carrier bombers from the carrier Junyo 200 miles north of Henderson. The robust Cactus Air Force fighter response throughout the day left no doubt that the airfield was still in operation.

October 25 found both sides groping in the dark.

That night both sides took steps that guaranteed that the carrier showdown would occur the next day. Making all preparations for the impending clash, Kinkaid designated Enterprise as the duty carrier for October 26 meaning she would handle all search and CAP duties. This kept Hornet’s air group as the designated strike group. Together, Enterprise and Hornet would bring 137 operational aircraft into the battle. Supporting air operations from Espiritu Santo would include an evening of the 25th PBY sortie for search with five more armed Catalinas. Ten more PBYs and six B-17s were scheduled to depart at 0330 on October 26 to re-establish contact with the Japanese.

At 1900, Kondo’s Advance Force headed south, followed an hour later by Nagumo’s carriers. The Vanguard Force took station 60 miles ahead of the carriers. From the three main force flight decks, and Junyo in the Advance Force, the Japanese brought to bear 194 operational aircraft thus outnumbering the Americans in every important category.

Throughout the 26th, the long-range American search aircraft were active and productive including PBYs and B-17s. Based on the early sightings, first blood was drawn by two Dauntless SBD’s from Enterprise on the Zuiho damaging the carrier significantly enough to take her out of the battle.

Enterprise SBD pilots Lt. Stockton Strong and Ensign Charles Irvine bomb the Zuiho. One of the Dauntless gunners shot down a Zero during the exit. Captain of the Enterprise recommended Strong for theMedal of Honor. Artist unknown.

At 0930 a B-17 spotted the IJN Advance Force and within minutes, a PBY spotted the Vanguard Force. Another PBY began to shadow Nagumo’s Main Body beginning at 1000 and within an hour had spotted all three of Nagumo’s carriers. The Japanese were reported to be steaming at 25 knots headed toward TF-61 355 miles to the west. As Kinkaid and his staff pondered possible actions, Halsey, who was in receipt of the same information, weighed in with new orders: “Strike, Repeat, Strike.”

The scouting aircraft of both opposing carrier groups having found each other began launching strikes. Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo launched his 65 aircraft first, then Rear Admiral Thomas Kinkaid launched his aircraft from Enterprise 20 minutes later. Rear Admiral George Murray launched Hornet’s aircraft 30 minutes after Enterprise. The total American strike totaled 73 aircraft. (Of note the strikes were not coordinated.)

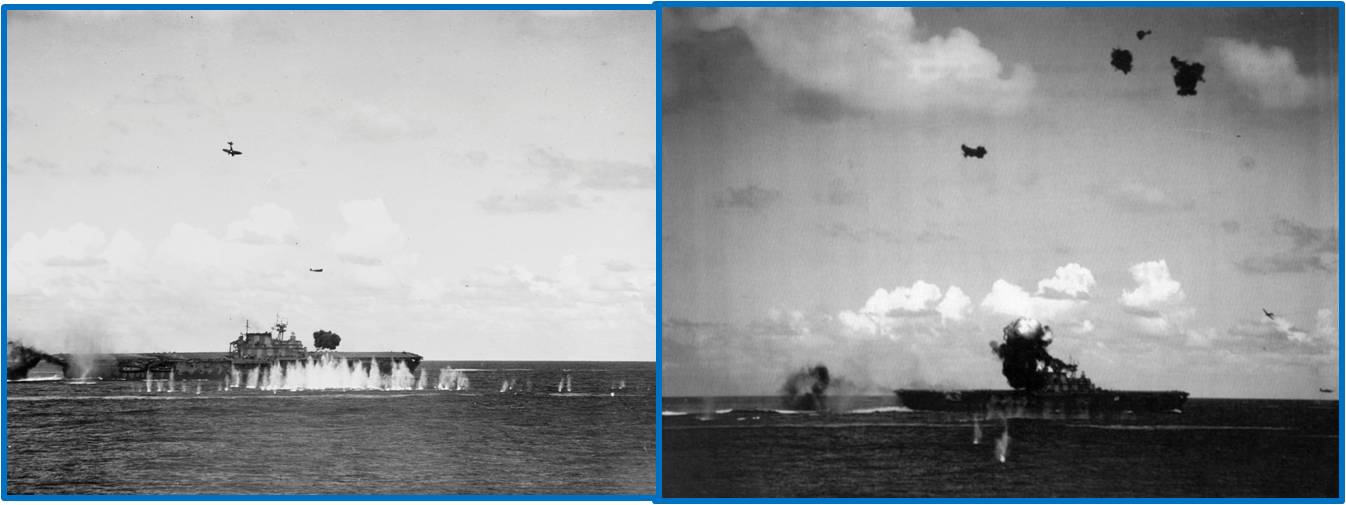

The Japanese found the American carriers first, but with Enterprise under a squall, Hornet was the only one the Japanese pilots saw, and reported back to Kondo. The attack on Hornet began around 0910 by the entire Japanese force and Hornet and her anti-aircraft screen defended with a heavy wall of flak. But within minutes of engagement, a bomb hit the starboard side of the flight deck aft, followed by the Japanese squadron commander crashing his damaged dive bomber into the carrier, glancing off the stack with the two still-attached bombs exploding.

Aichi D3A Type 99 Carrier Bomber crashes into USS Hornet (CV-8)

Finally, two aerial torpedoes struck in the engineering spaces, slowing the ship to a stop, creating an easy target for the dive bombers three quarter-ton bombs that struck her subsequently. One bomb penetrated four decks before exploding, causing serious fires underneath. Hornet was now completely crippled, but at a cost of 25 Japanese aircraft.

Considering the range/fuel, the first American aircraft launched did not wait for the later-launched aircraft. This resulted in the Enterprise aircraft reaching the Japanese first in a non-coordinated attack on the Shokaku group at 0930. The Japanese combat air patrol Zero fighters attacked these unescorted American SBD dive bombers and shot down or turned back several, but three to six of them still successfully planted their 1,000-lb bombs on Shokaku’s flight deck. The damage was so great that she was to be out of the war for the next nine months.

Hornet’s torpedo bombers never found Shokaku and instead launched their torpedo ineffectively at cruiser Suzuya around 0930 and headed home. Another group of aircraft, also from Hornet, also failed to find the Japanese carriers, and instead made their dives on cruiser Chikuma, exploding a bomb on the bridge and killing many senior officers.

Kondo very quickly figured out, based on the number of American attackers, that there must be two enemy carriers in the vicinity. While Hornet and her escorting destroyers fought the now raging fires on the carrier, he ordered a search and strike on the second carrier, finding Enterprise about 1000.

Enterprise under attack.

Anti-aircraft weapons from Enterprise and battleship South Dakota were very effective, with the carrier downing 7 aircraft and the battleship 26. Out of the 23 bombs released against Enterprise, only two hits and one near-miss were scored. The first hit exploded 50 feet under the forecastle deck, and the second crashed into the third deck before exploding. Despite damage, Enterprise was not disabled but her forward elevator was out of service creating problems for recovering and moving aircraft efficiently to the hangar deck.

The full exchange of carrier strikes from TF-61 and the four Japanese carriers resulted in significant damage to both sides. Two of the four Japanese carriers were mobile but flight deck damage put them out of action.

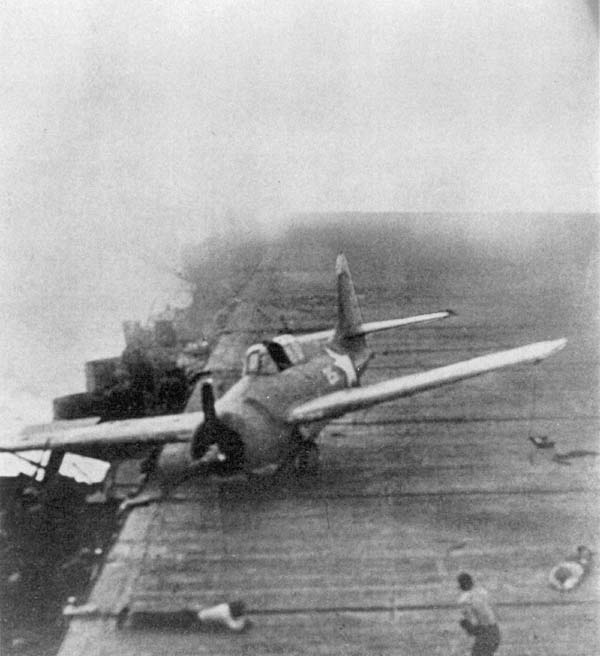

Knowing the Japanese would prepare to mount additional strikes, Kinkaid faced a very difficult situation. With Hornet dead in the water and attempts by heavy cruiser Northampton to begin towing the carrier only partially successful along with with Enterprise damaged, the TF-61 Commander faced the prospect of having to land all aloft aircraft on a single deck with no functioning forward elevator. He was certain that one or two undamaged Japanese carriers remained, but the aircraft recovery process made him unable to provide CAP over the crippled Hornet. To remain in the battle only risked the calamitous loss of Enterprise. With all this in mind, Kinkaid made the correct decision to completely withdraw and informed Halsey of his decision at 1135. U.S. surface ships retreated from the battle area accompanying Enterprise.

It was critical that Enterprise recover the aircraft from the two strikes and from CAP duty. As many as 73 aircraft were aloft – 28 Wildcats, 24 Dauntlesses and 21 Avengers. In the first phase of the recovery, 23 Wildcats and all 24 Dauntlesses were brought on board until the deck was unable to handle any more congestion.

Hornet Wildcat that had just landed skids across Enterprise‘s flight deck as the carrier maneuvers violently during Junyo‘s dive bomber attack.

Enterprise now had 84 aircraft on-board (41 fighters, 33 dive-bombers, and ten Avengers). The disaster of losing the bulk of the aircraft from the two air groups had been averted. Hornet was finally sunk during the night.

The Japanese had gained the upper hand and sought to finish off the surviving American flight deck. Nagumo and his staff tried to make sense of the morning’s action and decided that three American carriers were in action. One was the cripple often sighted during the morning and the other two were operating to the north and northwest of the cripple. At 1132 Nagumo radioed this assessment. Since the actual position of Enterprise was now south of Hornet, this erroneous assessment had the effect of sending the strike on a fruitless search in the wrong direction.

The air searches on the morning of October 27 revealed nothing, so after conducting a search for downed aviators in the area of the attacks on Hornet and Enterprise, Kondo headed his forces north.

The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands was over.

The Japanese carrier forces retired with significant damage to two carriers and high aircraft and aircrew losses. The wounded Shokaku and Zuiho returned to Truk on October 28, and the rest of the Japanese fleet arrived on October 30.

For the Japanese, the number of American carriers involved in the battle remained unclear. The early consensus was three, though no Japanese aviator had seen three separate American carriers. Yamamoto weighed in with an assessment that four carriers had been attacked and that one had sunk and the other three were badly damaged. This was also Nagumo’s view. All were sure that the “Naval Battle of the South Pacific” was a great victory.

The American forces were already in port when the Japanese dropped anchor at Truk. By the morning of October 27, TF-16 was northeast of Espiritu Santo with TF-17 close astern. On the afternoon of the next day, TF-61 arrived in the waters of Noumea.

The Japanese claimed a great victory with three carriers, one battleship, one cruiser, one destroyer, and one unidentified large warship sunk and 79 American aircraft destroyed (plus those that went down with the sunken carriers). This was an obviously excessive analysis, but the real losses were severe enough. Hornet was sunk along with the destroyer Porter. Enterprise was damaged, as was the battleship South Dakota, light cruiser San Juan, and destroyers Smith and Mahan damaged in a collision with South Dakota while exiting the battle area on October 27. Of the 175 aircraft at the start of the battle on the two carriers, 80 were lost to all causes (33 fighters, 28 dive-bombers and 19 Avengers).

Although Santa Cruz was a tactical victory and a short-term strategic victory for the Japanese in terms of ships sunk and damaged, and control of the seas around Guadalcanal, Japan’s loss of many irreplaceable veteran aircrews – particularly flight leaders – proved to be a long-term strategic advantage for the Allies, whose aircrew losses in the battle were relatively low and quickly replaced.

Part #20 will address analysis and impact of the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands.