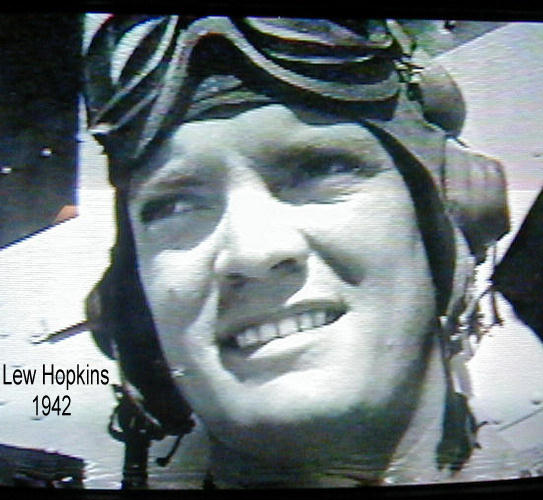

Testimony of Pilot# 15

Where do we get such men?

…From the farms and the fields of America, grown from boys who labor and look beyond the horizon toward better lives—for themselves and for their families.

The fields of Lewis Alexander Hopkins were red Georgia clay, and he saw the horizon along the backs and between the plow harness of Tom and Golden, the mule and the horse. After a long day, Lewis would trudge back home to a farmhouse with loose-fitting boards that let in the wind, a front porch where the family visited with neighbors, and with the outhouse down yonder.

That’s the way Anne Hopkins began the eulogy for her father, Rear Admiral Lew Hopkins – “from a farm in Georgia.”

Below are excerpts from an interview with her Dad for the oral history collection of Admiral Nimitz Historic Site-National Museum of the Pacific War, Center for Pacific War Studies in Fredericksburg, Texas.

Admiral Hopkins and his daughter Anne in a Dauntless.

Interview with

RADM. Lewis A. Hopkins (USN-Retired)

SBD Pilot (VB-6) – USS Enterprise –Battle of Midway

Mr. Cox: Today is January 15, 2004. My name if Floyd Cox and I am a volunteer at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas. We are here in San Antonio, Texas to interview Admiral Lewis Hopkins. Admiral Hopkins retired July 1, 1974 … Admiral, thank you for taking the time to visit with me today concerning your World War II experiences. I would like to start out just asking you some basic background questions about where you were born and your family.

[Hear the interview here]

Admiral Hopkins: I was born in a small community called Lutherville, Georgia in Meriwether county. It was an unincorporated area and I guess if you would draw a circle around what you would call a community there would have been about two hundred and fifty people there. It was a farming community with family farms. Everybody was very poor. We didn’t know it because everybody else was that way. I grew up on this farm and I guess you could call my Dad a share cropper. His mother had owned the land and had left the community and gone to Atlanta, Georgia and he was renting the land for one bale of cotton per year. Now whatever the price of cotton was determined what the rent was.

To put it in perspective, what you would make on the size of farm we had, you would make about five bales of cotton and one of those would go for the rent to his mother. It was a family farm. We had two animals, a horse and a mule and we did all the cultivation on the farm with those. I grew up in that farming atmosphere. Get up in the morning at sunrise, work until sunset, go to bed and get up the next morning and repeat the process. We had Saturday afternoon and Sunday off. Saturday afternoon we would get all cleaned up, we didn’t take a bath everyday in those days. … Farm work was hard work. It was manual work at that point in time with no mechanizations so to speak. Your cultivations were done with plows pulled by a horse or mule. When you worked a day it was a hard day’s work so at the end of the week you were ready to rest…. You grow up with things happening about you and you learn how to do them. It was a tough life but it was a good

I was fifteen years old when I graduated from high school. …

At that point in time you could work your way through college. I worked my way through four years of college for a total of something less than two hundred dollars. It was Berry College in Rome, Georgia. It was a small school and still is.

… I’ll have to tell you how I got in the Navy. I was doing this junior sales business in the spring of 1940 and I kept reading in the paper about the World’s Fair being held in New York. I kept thinking I would like to go to the World’s Fair. I didn’t have enough money as a junior salesman to go but I read in the Atlanta Constitution, Atlanta’s Daily Newspaper, one morning that the Atlanta Reserve Unit was going to take a two week cruise out of Charleston, South Carolina and layover in New York for a weekend. A light bulb went off in my head and I said, “I’m going out and join the Navy Reserve”….

I was living in a boarding house on the second floor. …I went down for breakfast and there on the dining table was the Atlanta Constitution with big headlines, “Atlanta Reserve called to duty”. That afternoon I went down to the Navy recruiting office and asked them what the Navy did besides peel potatoes and scrape paint. I had my college degree at that time and they told me I could go into flight training, which I did. In December 1940 I went into flight training in Opa Locka, Florida. Went through flight training there and at Jacksonville and went back to Opa Locka for advance training and so forth. I finished up in September 1941.

Mr. Cox: Was it at this point in time that you were selected to fly a certain type of aircraft such as fighters, bombers or the like?

Admiral Hopkins: I think now people have an opportunity saying what they would like to fly but on designation as an naval aviator I was assigned to carrier squadron on the USS Ranger which was out of Norfolk. I never got aboard the Ranger. I was in Norfolk in advanced carrier training squadron in preparation to go on board ship. When you are assigned to a carrier squadron one of the criteria and one of the things you want to get in your record is “carrier qualified”. If you make eight successful landings they put in your record “carrier qualified” but they never tell you what the qualifications are for the first one. I never got aboard the Ranger and I never got “carrier qualified” even though I was assigned. December 7th came along and they immediately transferred me and a lot of other people out to the west coast.

Mr. Cox: Do you remember where you were and what you were doing December 7, 1941?

Admiral Hopkins: I was in Pembroke, North Carolina. I had gone down over the weekend from Norfolk to Pembroke. It was about a six or seven hour drive by automobile. I was getting ready to back to Norfolk about two o’clock in the afternoon. I had gotten up from the couch and was standing in the living room and this radio message came on that the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. That is another one of those things that if that apartment was still there I could go back and say I was standing here when I heard about Pearl Harbor. I didn’t even know where Pearl Harbor was but they said in Hawaii….

We got on this ship and I don’t remember what the name of it was. The first thing they do is put us on watch. The USS Enterprise was out at that time on a raid on Marcos Islands so I was temporarily assigned to Bombing Squadron 3, which was stationed at Kaneohe in Hawaii and there is where I did all of my field carrier landing practice and qualified for carrier operations. I did all of this while the Enterprise was out to sea. I actually went aboard the Enterprise in early April 1942.

…. I got to the squadron and of course the commanding officer makes up the squadron organization. That was Commander Dick Best. He was a wonderful guy. I learned so much from him and I will always remember what a good leader he was. He took all of us under his wing. … I’ll always remember how much he thought about training us and he did the same thing in dive bombing. Scouting was one of our missions but dive bombing was our primary attack mission of course. He would go over every dive bombing flight and the dives. We used practice bombs that simulated real bombs that would put out smoke when your bomb would hit the ground or water. You could mark basically how many feet you were from the center of the target. He would go over that with you and talk about your dive, your angle of dive, your speed and release. We were, I guess you’d say, force fed. We would generally fly two flights a day. He was building up our capability. He was a wonderful skipper and VB Six was also quite an experienced squadron. There were three lieutenants, four or five junior grades and the rest of us were ensigns.

VB-6 in June 1942. Ens Hopkins is 7th from the left standing. Squadron Commanding Officer Dick Best is front row center.

I remember the first cruise was out on the Enterprise and when we left Pearl Harbor we were heading northwest. Day one Northwest, day two Northwest, day three Northwest and I thought the only place Northwest of here is Japan. So I was thinking, here I am on my first combat cruise on the Enterprise and we are going to attack Japan.

We went up every morning on the flight deck to check our planes and everything and I look out and see this carrier with  B-25’s (Mitchell bombers) on it. Then they told us about the USS Hornet. The story is of course that there was a Japanese picket ship that apparently got off a message, telling of the location of the USS Hornet, so they decided to launch the B-25’s early. That was April 18, 1942. I was sitting in the cockpit of my plane because as soon as the B-25’s were launched, they were going to launch us. I could see the B-25’s taking off.

B-25’s (Mitchell bombers) on it. Then they told us about the USS Hornet. The story is of course that there was a Japanese picket ship that apparently got off a message, telling of the location of the USS Hornet, so they decided to launch the B-25’s early. That was April 18, 1942. I was sitting in the cockpit of my plane because as soon as the B-25’s were launched, they were going to launch us. I could see the B-25’s taking off.

[Returning from the Doolittle mission]… We didn’t know anything about what was going on but obviously you sense something. Basically they didn’t want any radio transmission because that would tip off the Japanese that the ships were going back to Pearl Harbor for whatever reason. We wanted them to believe that the ships were still down in the southwest Pacific. When we got back to Pearl Harbor there is a whole lot of activity getting everything ready to go.

After we left Pearl Harbor and about the second day out going toward Midway was when they told us pilots that the Japanese were going to attack Midway and we would be north of the island of Midway in sort of an ambush situation. But that was the first that we knew about it and we also were told that we could expect the PBY’s 2 flying off of Midway to be the first ones to sight the Japanese, which turned out to be the case.

Mr. Cox: Let’s go back to June 4, 1942. You fellows knew that some action was pending, can you take it from there?

There has been so much talk about the Battle of Midway and the breaking of the code and all of that sort of thing so whenever I am asked to give a talk, I title my speech “Ensigns at Midway” to kind of give it a little different flavor. I point out that, yes we broke the code which enabled Admiral Nimitz to make a major decision, but somebody had to carry the bombs. That is where the ensigns came in. I think on the morning of June 4th there were twenty-nine ensigns flying the mission.

On the morning of June 3rd there were a couple of reports but at that time the carriers had not been sighted. The first indication was on June 4th when the PBY’s saw the attack planes coming in from the carrier to attack the Midway. You didn’t really know where the ships were. You just knew they probably were out somewhere on this line of bearing 320 degrees from the island of Midway.

Mr. Cox: Can you remember, as a young man at the time, how you felt knowing that some serious action was going to be taken?

Admiral Hopkins: I can’t say that I was scared but I was certainly concerned and the atmosphere in the ready room was small talk and that sort of thing. Of course we were busy keeping track of navigation and all. On the morning of June 4th we had gotten up about one o’clock and gone down and had breakfast. I don’t think anyone was very hungry and they kind of pushed their eggs around. The time just seemed to drag. Then the reports started coming. You get these reports and you start wondering, what, are we going to do. We all had our plane assignments. My plane was 6-B-12, #4684.

… We got up about one o’clock in the morning and went down and had breakfast of a sort. I don’t think anyone was particularly hungry and then went to the Bomber Six ready room. The ready room was quite nice in that they had nice chairs with an arm that swung over in front of you that you could put your navigation board on. We called them plotting boards.

You could put a lot of information on there about what the wind speed was, the ships position was and the estimated ships course of speed would be after you had been away for awhile and would return. You had to take all of those things into consideration. You would put down any information that was provided by the reports that came in regarding the the number, location and estimated speed of the Japanese ships that were being reported by the PBY aircraft.

There were some sketchy reports coming in early but not sufficient enough to know precisely what was happening. The first very concise report that came in was from a PBY out of Midway reporting Japanese planes coming in on a certain heading to attack Midway. That was the first concrete information we had. That was early in the morning and there we were sitting in the ready room wondering when we were going to take off.

As I had said, there was a lot of small talk. Obviously, we were just making conversation. Every once in a while there would be some real significant conversation going on but it was kind of a nervous waiting situation.

As I had said, there was a lot of small talk. Obviously, we were just making conversation. Every once in a while there would be some real significant conversation going on but it was kind of a nervous waiting situation.

Of course at that time we all had our plane assignments. As I previously stated, I had plane 6-B-12. We knew where we our planes would be spotted on the deck. Scouting Six would be spotted on the deck ahead of Bombing Six. Scouting Six had eighteen planes and Bombing Six had fifteen. I was number twelve in Bombing Six, so if you look at it in take off sequence there were eighteen planes plus eleven planes that were to go before me so I was going to be the thirtieth plane to take off. Consequently; I could watch all of the others take off. The Scouting Six planes by virtue of being forward on the deck had less of a take off run than the Bombing Six planes had. As a result, they carried smaller bombs.

As time went by finally at seven o’clock they said, “Pilots man the planes.” It is an interesting thing on a carrier because up until that point in time the people were just doing various jobs on the carrier deck and when they say, “Pilots man your planes” it just becomes a beehive of activity. The pilots are all coming out in a group checking their planes and looking everything over. They always kick the tires, as if that would tell you anything. Everybody starts their engines and you have propellers turning and everything

Mr. Cox: Where did they hang the bombs on your plane?

Admiral Hopkins: Under the belly of the plane in a yoke type of device. When you released the bomb instead of the bomb going directly forward the yoke would slant down and then it would release so the bomb would clear the propeller. We had a thousand pound bomb. By the way, that was the first time I ever took off with a live bomb. I wasn’t the only one either, there were lots of other pilots who had the same experience.

of device. When you released the bomb instead of the bomb going directly forward the yoke would slant down and then it would release so the bomb would clear the propeller. We had a thousand pound bomb. By the way, that was the first time I ever took off with a live bomb. I wasn’t the only one either, there were lots of other pilots who had the same experience.

Mr. Cox: After Scouting Six took off and your take off rotation came up and you took off, what altitude were you flying and did you see the Japanese fleet right away?

Admiral Hopkins: Oh no. When you take off from the carrier it is kind of like a ballet actually. You have the planes circling and you have all the other planes coming around on the inside of the circle. It is just a string of planes coming around as you are going up. As we joined up we climbed to twenty-two thousand feet.

From a selection of color photographs of SBD Dauntless dive bombers shot “somewhere in the Pacific” for LIFE magazine.

We had to use oxygen and that was another first. I had never used oxygen on a continuous basis other than in an oxygen chamber when they showed you how to use it. The oxygen masks in those days were pretty flimsy. As a matter of fact some of our pilots had a problem and my squadron commander, Dick Best had to reduce the altitude slightly.

We went out on this mission and we get to where the the Jap fleet was supposed to be, they are not there. There was nothing. Just ocean as far as you can see and at this point in time we are just about as far as we should be if we wanted to get back to the carrier. We were at the point of no return. Wade McCluskey, who was the Enterprise Air Group Commander, made the decision to go ahead and see if he could find them. He went about another fifteen minutes and I knew and most everybody else knew that we didn’t have enough fuel to get back. He turned northwest and he ran across this destroyer hightailing it back to the rest of the Japanese fleet and he decided to follow it. We are flying in formation so we follow. I mentioned how you can be impressed with an image and I remember seeing the Japanese fleet. I am sitting here today and I can see that Japanese fleet as clear now as I saw it then. It was something else and I was clearly impressed.

I’m not sure the true story has ever been confirmed as to what happened relative to the assignment of the ships. The story that Dick Best tells is that he was supposed to attack one ship, which was the Kaga, and when he gets in position to do so, McCluskey is attacking that ship, so he diverts to the other ship, which was the Akagi. At almost the precisely the same time coming from another direction was Bomber Squadron Three from the Yorktown who had better information about the ships location at the time they took off. The Japanese were amazed that an attack could be so well coordinated that two attacking forces, approaching almost one hundred and eighty degrees from each other, could converge upon their fleet at precisely the same time.

… There were three bomber squadrons. Bomber squadron SIX, Scouting Squadron SIX, both from the Enterprise, and Bomber Squadron THREE, which was from the Yorktown, did the damage. It all happened in six minutes. From ten twenty to ten twenty-six. At ten twenty the Japanese carriers had not been touched. At ten twenty-six three of them were headed for the briny deep.

Mr. Cox: Did you see the torpedo planes going in or any fighters?

Admiral Hopkins: No, I did not see any torpedo planes and the amazing thing was there were no fighters. There were no fighters until we got down. We didn’t have any resistance. They didn’t even have any aircraft fire. They didn’t see us. The Japanese side of this tells about people on the deck and they don’t see the SBD’s until some of them are actually in their dive. They see at that point in time that it is too late to do anything about it. I was twelfth position in the formation so there were eleven ahead of me in the dive.

You see four or five ahead of you in the dive and you see the bombs dropping and they pull out. I went down at a dive angle of about sixty to seventy degrees. The plane has split flaps and you get 240 knots is about the maximum speed with the split flaps.

In those days you had what you call a gun sight that is a tube with cross hairs in it. You look through that and in the meantime you are flying the plane and you have to keep it balanced. I put the cross hairs on the leading edge of the carrier. The radioman called out the altitude, five thousand, four thousand, three thousand, twenty-five hundred because when you are looking in the cross hairs you can’t see the altimeter. He calls twenty-five hundred and a Zero coming from the right. I went ahead and released the bomb and immediately turned in to the Zero in a defensive maneuver.

I think post analysis showed that I didn’t get a hit. Usually you can drop your bomb and make a left turn and look back over your shoulder and see your bomb hit. I didn’t have that opportunity since I was busy with the attacking zero. I got down on the water as close as I could and Anderson the gunner says, “Let’s get the hell out of here.” I said, “What do you think I’m trying to do?” Basically we are in the middle of the Japanese fleet when we pull out. Now the problem is, how do I get back to the ship because our fuel is low.

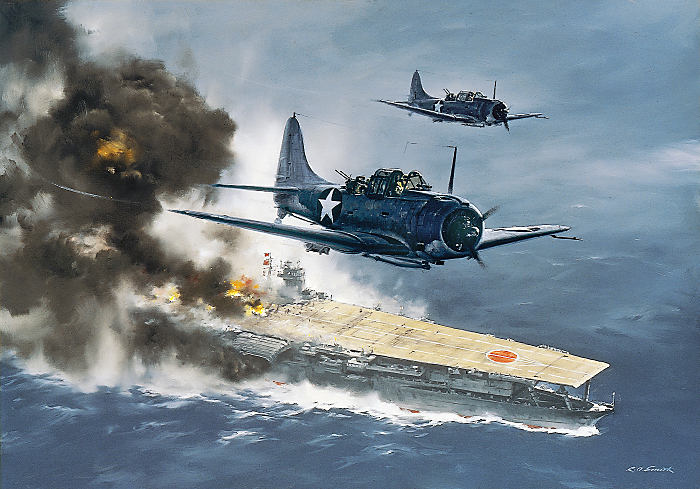

“SBDs over Akagi” by R.G. Smith

I was joined up by two other planes flown by ensigns, Ensign Green and Ensign Ramsey. We got about forty miles out from the Enterprise and Ensign Green runs out of fuel and so he has to ditch. There is nothing I can do but take note of the location. We get within sight of the carrier and Ensign Ramsey runs out of fuel and I make a note of that. When I get back to the carrier I found that I am one of five planes that made it back to the carrier. Why me? I guess you could say I might have managed my fuel a little better or maybe the engine itself made it possible. No two engines perform in the same way. Anyway I got back o.k.

Mr. Cox: I guess you could say that the Man upstairs was looking out for you.

Admiral Hopkins: I guess so. I told you about this Battle of Midway Round Table that is on the Internet. One of the questions that was asked of everybody on the round table, one time was, who was the most responsible person in the victory at the Battle of Midway. Well, you get all kinds of answers but one of the answers was God and luck. You cannot say that there wasn’t luck involved. Now whether God was involved, I guess that could be the subject of a lot of discussion, but certainly there was luck involved and a lot of hard work.

This action occurred the morning of the 4th . I did not fly the afternoon mission. … that was when the fourth carrier was sunk. The battle was over that day.

The battle was over that morning although planes from the Hiryu did badly damage the Yorktown. The morning of the 5th we were kind of marking time because nobody knew where the Japanese fleet was and they kind of conjectured that there might be another carrier out there. By the way the Hornet planes never got into the June 4th morning action at all.

On the 5th they got all of the SBD’s that they could fly and I think there were fifty-eight of them total. We launched out to the Northwest, hoping we would find a carrier but we didn’t. We went past this lone destroyer and finally decided it wasn’t a carrier. We decided we would attack the destroyer and fifty-eight planes dived on it and there wasn’t a single hit. We found out in a postwar Japanese report that one of the officers lay on the deck looking up watching the planes coming in and he was telling the ship’s Captain how to maneuver. Hitting a destroyer is not easy.

Mr. Cox: Compared to a carrier?

Admiral Hopkins: Even a carrier is not easy. If you look at the number of dives on a carrier and the actual hits reported it is not an easy target. But anyway, fifty-eight planes missed the destroyer. This was late afternoon so now we have to find the ship at night and land in darkness. Luckily the Task Force Commander turned the lights on. I was in this group and I had never made a night carrier landing. I had never even practiced one. One other person in our squadron was also making his first night landing.

Mr. Cox: Do you remember your feeling at the time?

Admiral Hopkins: Well, I know I was concentrating but actually it really wasn’t too different than a daylight landing. The Landing Signal Officer had lighted wands to guide you in and your landing pattern was exactly the same as during day light. I kind of wondered about it a little bit.

Mr. Cox: Did they lose any planes during the landing?

Admiral Hopkins: No. We lost one plane that was shot down during the attack on the second day.

Mr. Cox: On the first day during the attack were any planes lost from your division?

Admiral Hopkins: Oh yes. Only five planes out of my squadron got back. I don’t know about Scouting Six. I think all of Bombing Three planes got back. The torpedo planes took tremendous losses.

Mr. Cox: Did you see any planes go in the water during the attack?

Admiral Hopkins: The only two planes I saw go in were the two that ran out of gas. The doctrine at that time was to make a coordinated attack. The torpedo planes and dive bombers at the same time. The fighters were for protection but there weren’t any at that time. The torpedo planes took all the Zeros down to allow the dive bombers to attack unopposed. That was a major factor.

… June 6th and we went back to Pearl Harbor. I was immediately reassigned to Scouting Squadron Eight on the U.S.S Hornet. .. we went down to the southwest Pacific around the Guadalcanal area. While we were down there the USS Saratoga was hit. The USS Wasp was hit and sank.

[RS note: When the USS Wasp was torpedoed off Guadalcanal in September ’42, Hornet’s squadrons were flown off to Espiritu Santo so planes from the Wasp could land on the Hornet. Unable to find the island in night stormy weather his flight was forced to crash land He got malaria from being on the island, thus was not able to fly at the Battle of Santa Cruz. When Hornet was bombed and sunk he was moved to a destroyer and eventually then transferred back to the States.]

When I got back to San Francisco I told them I was perfectly willing to back to the Pacific, but they said, “No, we want you to go and train dive bombing pilots.” This was December l942. I went to Cecil Field in Jacksonville and trained bombing pilots….

The concluding lines of Anne’s Eulogy:

Lewis is gone forever, but I like to think that in some forsaken corner of our troubled globe, another child like Lewis, will be born to rise from humble beginnings to lead another family, another country, and a better world. And, when that next body withers and dies, that another fortunate and grateful child like me will stand before a roomful of friends and family to ask and answer, again, the question…

Where do we get such men?

Ensign Lew Hopkins was awarded the Navy Cross for his combat actions at the Battle of Midway.

Ensign Lew Hopkins was awarded the Navy Cross for his combat actions at the Battle of Midway.

When Enterprise returned to Pearl Harbor he was assigned to Scouting Squadron Eight (VS-8) onboard USS Hornet still flying the SBD Dauntless. After return from the Guadalcanal campaign he was given orders to train dive bombing pilots in Jacksonville, Florida, and then to evaluate mission adaptability for the F4U Corsair and the Dauntless.

He received post graduate training at Annapolis and Renssalear Polytechnic Institute for a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering and spent the remainder of his career in research, development and aircraft logistics. He commanded the Naval Missile Center at Point Mugu and retired as a Rear Admiral Upper half in 1974 as Chief of Research and Development, Naval Air systems Command, in Washington DC.

He received post graduate training at Annapolis and Renssalear Polytechnic Institute for a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering and spent the remainder of his career in research, development and aircraft logistics. He commanded the Naval Missile Center at Point Mugu and retired as a Rear Admiral Upper half in 1974 as Chief of Research and Development, Naval Air systems Command, in Washington DC.

A similar video interview can be found at The National World War II Museum website.