Testimony of Pilot# 16

MEDAL OF HONOR citation… for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while Senior Naval Officer in the Prisoner of War camps of North Vietnam on 4 September 1969. Recognized by his captors as the leader in the Prisoners’ of War resistance to interrogation and in their refusal to participate in propaganda exploitation, Rear Admiral Stockdale was singled out for interrogation and attendant torture after he was detected in a covert communications attempt…

… Sensing the start of another purge, and aware that his earlier efforts at self-dis-figuration to dissuade his captors from exploiting him for propaganda purposes had resulted in cruel and agonizing punishment, Rear Admiral Stockdale resolved to make himself a symbol of resistance regardless of personal sacrifice. He deliberately inflicted a near-mortal wound to his person in order to convince his captors of his willingness to give up his life rather than capitulate. He was subsequently discovered and revived by the North Vietnamese who, convinced of his indomitable spirit, abated in their employment of excessive harassment and torture toward all of the Prisoners of War. By his heroic action, at great peril to himself, he earned the everlasting gratitude of his fellow prisoners and of his country…

Always Leading and Always Will

by Orson Swindle (USMC, Ret)

with add by Paul Galanti (USN, Ret)

Prisoners of War in North Vietnam

[Reproduced with permission of USNI and the author]

The country, the Navy, the Stockdale family, especially his beloved wife, Sybil, and those of us who were POWs in North Vietnam suffered a terrible loss with the passing on 5 July (2005) of Vice Admiral James B. Stockdale. Husband, father, patriot, mentor, author, and dear friend, he touched our lives profoundly. Distinguished graduate of the Naval Academy, Medal of Honor recipient, courageous warrior, brilliant leader, almost bigger than life, he never stopped inspiring us. It is difficult to accept that he is gone. We recognize how fortunate we are that he came our way.

The POW experience was a real-time laboratory on leadership. Led by Admiral Stockdale’s example, we prisoners lived and struggled to return with honor. He inspired each of us to lead in the most bizarre and painful of circumstances where to accept the mantle of leader meant certain suffering. But accept it we did.

I first encountered Jim Stockdale many years ago, and he changed my life.

Late spring 1967 was a bad time for POWs in Hanoi. I was in my sixth month of imprisonment, living alone in a small windowless cell. I was not feeling good about myself, having broken under torture and written a propaganda statement. These were trying times, testing our spirit, our will, and our physical and mental stamina.

Our cellblock, occupied by about 18 junior officers, consisted of ten cells. We communicated with each other by tapping on walls or lying on the filthy floor, peeking under the door to be sure the guards had left the area and then whispering along the passageway. Communicating was forbidden. The price for getting caught was solitary or torture.

But communicating was our lifeblood; we never stopped. For me, with my morale sinking, whispering and tapping with other POWs was enabling me to hang on. Late one evening I heard the muffled sounds of guards moving a new prisoner into a cell block about three cells down from me. The next day, when the guards vacated the block, I was down on the floor whispering to the “new guy,” asking him to identify himself and join in the communications stream. Commander James Bond Stockdale checked in.

I was overwhelmed by his presence. Here next to me was our leader, a prisoner since 1965 and the senior Navy captive, and I was in direct contact with him. We were faintly aware of his most recent ordeal. Our admiration for him is difficult to describe. In the days that followed, Jim was not communicating much, as he was recovering both physically and mentally from pain recently inflicted. Sadly, there was to be much more suffering for him.

One day we young officers were discussing some issue and finding no answers. I whispered down the passageway, “Hang on for a minute, and let me ask the Old Man what we should do.” Commander Stockdale came up after a couple of calls, and responded with a wise answer to our problem.

Now fast forward to February 1973, almost six years later. We have been told we are going home. In the large courtyard area of Ho Loa prison (the Hanoi Hilton), the North Vietnamese are allowing one large cell of Americans at a time to wander over to the recently uncovered windows of other cells that surrounded the courtyard, permitting conversation. I see a slight man, terribly worn and tired looking with very grey hair limping over to my window. He looks up at me, smiles, and says, “Hi, I’m Jim Stockdale, who are you?” We literally had never seen each other before.

Now fast forward to February 1973, almost six years later. We have been told we are going home. In the large courtyard area of Ho Loa prison (the Hanoi Hilton), the North Vietnamese are allowing one large cell of Americans at a time to wander over to the recently uncovered windows of other cells that surrounded the courtyard, permitting conversation. I see a slight man, terribly worn and tired looking with very grey hair limping over to my window. He looks up at me, smiles, and says, “Hi, I’m Jim Stockdale, who are you?” We literally had never seen each other before.

I reply, “Sir, I am Orson Swindle, Marine, and I want to thank you for your leadership and the inspiration you have provided to me, to all of us. Your leadership and personal conduct helped me survive these past six years. You very likely saved my life.”

I continue, “I remember a day back in the spring of 1967, when you moved into my area of the cell block. My morale and self-esteem were pretty low then. I was really down on myself. I recall how having you around and knowing what you had endured reminded me of my duty, my obligations, and what was expected of me. You inspired me by your mere presence. I am eternally indebted to you.”

Jim smiles and says, “Orson, I remember you and those difficult days so well. I was really depressed and down on myself, too. I want you to know that when you whispered, ‘Hang on for a minute, and let me ask the Old Man what we should do,’ you reminded me of who I was and of my duty to each of you. Orson, you helped me survive, too.”

It is said that leaders are like eagles. They don’t flock. You have to find them one at a time. Jim Stockdale was an eagle. To paraphrase President Reagan, most people go through life wondering if they had made a difference. Jim Stockdale did not have that problem.

Add by fellow POW Paul Galanti:

In September, 1965, when Cdr. Jim Stockdale was shot down over North Vietnam, my squadron commanding officer, Cdr. Tex Birdwell — one of the toughest men I’d ever known, who’d worked with Stockdale at the Navy Test Pilot School — said, “Jim’ll do all right, he’s the toughest guy I know.” Commander Bill Franke, a contemporary of Stockdale’s when shot down, was the smartest human being I’d ever known. He served on the test pilot faculty with Stockdale. Franke told me, “Jim is the smartest human being I’ve ever known.” Those two endorsements say a lot about Jim Stockdale — a very tough guy who led others with his intellect.

“CAG” (Commander of the Air Group) was the last of a breed and one of the great bargains Uncle Sam received in exchange for his Annapolis education. A brilliant man, Stockdale excelled in the primarily engineering curriculum of the Academy class of 1947. He wound up flying fighters, earning an MS in Engineering, and becoming head of academics at the Navy Test Pilot School — where his students included four of the earliest astronauts, three Navy and one Marine.

BUT IT WASN’T the tailhook carrier Navy that excited Jim Stockdale the most. Working toward his doctorate in philosophy, he studied the classics for two years under Stanford’s renowned philosophy professor Philip Rhinelander. He became fascinated with the Stoics. Particularly in Epictetus’ Enchiridion, Stockdale found his raison d’etre as a leader of men in a POW environment. His nearly eight years in a Communist prison with frequent torture, solitary confinement, and endless mind games played by his captors made him stronger. He would later tell audiences that he believed his whole life directed him to be the inspirational leader for the 600 military POWs in Vietnam. He got through nearly five years of solitary confinement convinced that it was his purpose to be there.

Stockdale’s 2,713 days of leadership in isolation resulted in promotions to admiral and general, selections for choice assignments, and a plethora of medals for the men he inspired. He was personally awarded the Medal of Honor in large part for refusing to be exploited by being forced to order Americans to violate their Code of Conduct.

His brief foray into politics as the reluctant vice-presidential candidate for Ross Perot in 1992 didn’t work out. But one of the memorable moments of the campaign was the vice-presidential debate with Dan Quayle and Al Gore, and Admiral Stockdale. The pundits had a field day with the geezer against the hip, one-thought-equals-one-clever-bumper-sticker Quayle and Gore. Admiral Stockdale looked at the camera and asked famously, “Why am I here?” Neither Quayle, Gore, the press, nor the viewers understood what he was saying. But those of us who served with him in Hanoi understood very well.

He was imploring the spirit of Epictetus to whisk him away from these buffoons back to his destiny: leading men under very trying circumstances. According to Epictetus, Jim Stockdale knew, that was his life’s principal destiny. And for so many of us POWs, it — and he — made all the difference.

Orson Swindle, a USMC fighter pilot, flew more than 200 sorties in the F-8E Crusader during the Vietnam War. On November 11, 1966, Swindle’s Crusader was shot down while on a mission over the Quang Bình Province, North Vietnam. He spent the next seven years in various prison camps, including the notorious Hanoi Hilton complex. He was released on March 4, 1973. Swindle retired as a lieutenant colonel in 1979. Subsequently he served as Assistant Secretary of Commerce during the Reagan Administration and later as Commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission,

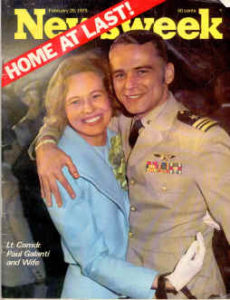

A retired Navy pilot, Cdr. Paul Galanti of Richmond flew 97 combat missions in his A-4 Skyhawk before being shot down and captured on June 17, 1966, spending nearly seven years as a POW. Galanti’s wife, Phyllis, succeeded Stockdale’s wife, Sybil, as head of the POW wives’ group that worked tirelessly for the humane treatment and return of all POWs from Vietnam.

A retired Navy pilot, Cdr. Paul Galanti of Richmond flew 97 combat missions in his A-4 Skyhawk before being shot down and captured on June 17, 1966, spending nearly seven years as a POW. Galanti’s wife, Phyllis, succeeded Stockdale’s wife, Sybil, as head of the POW wives’ group that worked tirelessly for the humane treatment and return of all POWs from Vietnam.