Blown Slick Series #13 Part 10

Watchtower

Guadalcanal is no longer merely a name of an island in Japanese military history. It is the name of the graveyard of the Japanese army.

—Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi, IJA

Commander, 35th Infantry Brigade at Guadalcanal

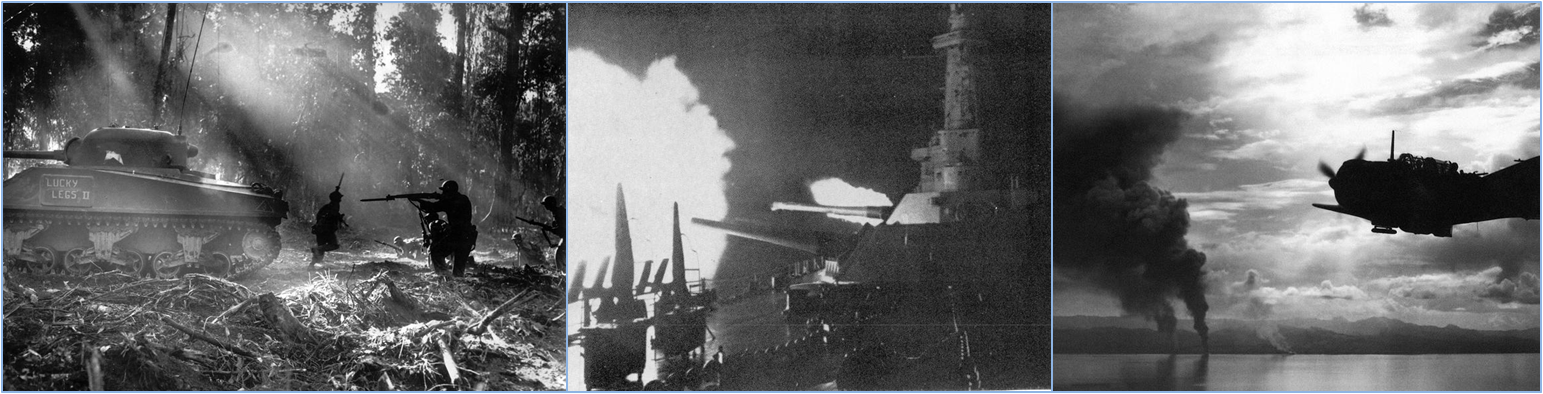

As noted in Part #9, unlike Midway which was almost entirely a carrier vs. carrier battle, the fight to gain and hold Guadalcanal was a land, sea, land-based air, and sea-based air six month give and take. Each element was dependent on the other and the equality of the Japanese and American carrier airpower played a major part in neither side gaining

lasting superiority and drove how each side chose to attack and defend. It was one thing to defend Midway operating in open ocean; being closely tied to the geography of the island and surrounding waters to provide air support was a whole other thing. With intelligence far inferior to that during Midway, staying in one general area exposed the carriers to submarine, land and sea based attack. There was much to be learned – at the expense of all participants.

While the over arching series is focused on airpower, the sub-series focuses on examining that first year of war in the Pacific and the emergence, growth, and operational use of the aircraft carrier. It seems worthwhile to the endeavor to comprehend the total land-sea-air conflict environment of the Guadalcanal Campaign if one is to really appreciate the 1942 need for the capability of carrier airpower to be recognized and applied effectively. That particularly requires recognizing the limitations imposed by the threat environment, along with the emerging requirements to support expeditionary warfare (best example, close-air-support communications and coordination was non-existent and was not yet part of navy pilot training). Operational learning in this emerging warfare environment was also critical in regard to preparation for support of the planned operations of 1943-45 along the pathway to Japan itself. Indeed carrier aviation in 1945 would barely resemble that of ’42. Although somewhat lengthy, context and brief reference are necessary. Continued below are abbreviated summaries of the main battles of the Operation Watchtower campaign.

The Battles of Guadalcanal –

1. Operation Watchtower (7 August 1942)

At dawn On 7 August 1942, Allied forces, predominantly United States Marines, landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida in the southern Solomon Islands, with the objective of denying their use by the Japanese to threaten Allied supply and communication routes between the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. The Allies also intended to use Guadalcanal and Tulagi as bases to support a campaign to eventually capture or neutralize the major Japanese base at Rabaul on New Britain. The Allies overwhelmed the outnumbered Japanese defenders, and captured Tulagi and Florida, as well as the airfield under construction on Guadalcanal.

(Initial Carrier air support is the subject of a separate post)

2. The Battle of Savo Island (9 August)

Shortly after midnight on 8–9 August, the Japanese counter-attack came. An eight-ship (five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and a destroyer) Japanese force slipped undetected past two radar-equipped U.S. destroyers and attacked multiple devastating hits by Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedoes two groups of Allied heavy cruisers and destroyers guarding the western approaches to the U.S. invasion force, which was still hectically engaged in landing supplies to support the Marines ashore. When it was over, four allied heavy cruisers were sunk and a heavy cruiser and a two destroyers damaged, with 1,077 allied Sailors killed in what CNO Admiral Ernest J. King would describe as the “blackest day of the war.” Pearl Harbor was one thing, but to have suffered such a severe one-sided loss by a force whose very purpose was to guard against such an attack was a severe psychological blow.

The Japanese commander, Rear Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, did not know that only one heavy cruiser and two light cruisers were the only major ships between him and dozens of U.S. supply ships and U.S. troop transports. But, fearful of being attacked by carrier aircraft at dawn (and not knowing that the three U.S. carriers supporting the landing were already steaming away from the area), in addition to having received wildly inflated reports about how many U.S. ships had been destroyed in three major Japanese air attacks over the previous two days, Mikawa opted to withdraw back to Japanese bases over 500 miles to the northwest.

Nevertheless, with no air cover, and concerned over a follow-on night surface attack, the result was an ignominious withdrawal of U.S. Navy forces the next day from the immediate Guadalcanal area, effectively leaving the Marines ashore to fend for themselves, and leading to the oft-repeated statement that the U.S. Navy abandoned the Marines at Guadalcanal (although at that time the only Japanese remaining on the island were the remnants of construction units that had been building the airfield). For more on the disaster at Savo Island please see attachment H-009-1.

– Henderson Field and the Cactus Air Force

After capturing the partially completed Japanese airfield, construction work began on the airfield immediately, mainly using captured Japanese equipment. On 12 August, the airfield was renamed Henderson Field, for Major Lofton R. Henderson, who was killed during the Battle of Midway. By 18 August, Henderson Field was ready for operation and along with its “Cactus Air Force” became the focal point both offensively and defensively for both sides throughout the rest of campaign.

The first Marine pilots arrived on 20 August, flying from the escort carrier USS Long Island. They included 18 F-4F Wildcat fighter planes of VMF-223 and a dozen SBD Dauntless dive bombers of VMSB-232 . These warplanes conducted combat missions the following day.

They were joined on 22 August by the U.S. Army’s 67th Pursuit Squadron with five Army P-400s (an “export” version of the P-39); and on 24 August by 11 SBD dive bombers that came from the USS Enterprise.

3. Initial Ground Operations and First Battle of the Matanikau (19 August)

The 11,000 Marines on Guadalcanal initially concentrated on forming a loose defensive perimeter around Lunga Point and the airfield, moving the landed supplies within the perimeter and finishing the airfield. In four days of intense effort, the supplies were moved from the landing beach into dispersed dumps within the perimeter. Work had begun on the airfield immediately, mainly using captured Japanese equipment.

On the evening of 12 August, a 25-man U.S. Marine patrol, led by Lieutenant Colonel Frank Goettge landed by boat west of the US Marine Lunga perimeter, east of Point Cruz and west of the Japanese perimeter at Matanikau River, on a reconnaissance mission with a secondary objective of contacting a group of Japanese troops that U.S. forces believed might be willing to surrender. Soon after the patrol landed, a nearby platoon of Japanese naval troops attacked and almost completely wiped out the Marine patrol. On 19 August, three companies of the U.S. 5th Marine Regiment attacked the Japanese troop concentration west of the Matanikau. This was the first of several major actions around the Matanikau River.

The map below shows how the Matanikau, Lunga, and Tenaru Rivers bracketed the area around Henderson Field and were the geography for much of the land war.

4. Battle of the Tenaru River (Aug. 21)

In response to the Allied landings on Guadalcanal, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters assigned the Imperial Japanese Army’s (IJA) 17th Army, a corps-sized command based at Rabaul and under the command of Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake, the task of retaking Guadalcanal. The army was to be supported by Japanese naval units, including the Combined Fleet under the command of Isoroku Yamamoto, which was headquartered at Truk.

The Battle of the Tenaru, sometimes called the Battle of Alligator Creek was the first major Japanese land offensive during the Guadalcanal campaign.Just after 3:00 a.m. Japanese assault forces – primarily members of the elite Japanese Special Naval Landing forces – attacked U.S. Marine positions east of the airfield. At one point, the enemy broke through and the fighting degraded into a savage hand-to-hand struggle with knives, machetes, swords, rifle butts, and fists. The Marines held their positions through subsequent Japanese attacks and inflict heavy losses.

5. Battle of the Eastern Solomons (24 August)

(Note: subject of a separate post)

The third carrier battle of World War II, which took place in open waters northeast of the Solomon Islands on 24 August, was a victory for the U.S. Navy by a very narrow margin. When the incredibly chaotic battle was over, the Japanese light carrier Ryujo had been sunk, with the loss of all but one of her 35 aircraft. The Japanese lost 75 aircraft (64 carrier aircraft) and, unlike Midway, most of their crews were not recovered. Including aircrew, about 300 Japanese died.

The result of the battle was that the big Japanese push to reinforce Guadalcanal fizzled, and the large Japanese force withdrew after yet another failed attempt to draw U.S. Navy forces into a night surface battle.

6. Battle of Edson’s Ridge (12–14 September)

The Battle of Edson’s Ridge, also known as the Battle of the Bloody Ridge was a land battle in which U.S. Marines repulsed an attack by the Japanese 35th Infantry Brigade. The Marines were defending the Lunga perimeter that guarded Henderson Field. It was the second of three separate major Japanese ground offensives during the Guadalcanal Campaign.

Underestimating the strength – about 12,000 – of Allied forces on Guadalcanal, 6000 Japanese soldiers conducted several nighttime frontal assaults on the U.S. defenses. The main Japanese assault occurred around Lunga ridge south of the airfield , manned primarily by troops from the 1st Raider and 1st Parachute Battalions under U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel Merritt A. Edson. Although the Marine defenses were almost overrun, the Japanese attack was ultimately defeated, with heavy losses.

7. Second and Third Battles of the Matanikau (23 – 27 September and 6 – 9 October)

The Actions along the Matanikau—sometimes referred to as the Second and Third Battles of the Matanikau—were two separate but related engagements, which took place in the months of September and October 1942, among a series of engagements between the Marines and Imperial Japanese naval and ground forces around the Matanikau River. These particular engagements -the first between 23 and 27 September, and the second between 6 and 9 October – were two of the largest and most significant of the Matanikau actions.

In the first action, elements of three U.S. Marine battalions attacked Japanese troop concentrations at several points around the Matanikau River. The Marine attacks were intended to “mop-up” Japanese stragglers retreating towards the Matanikau from the recent Battle of Edson’s Ridge, to disrupt Japanese attempts to use the Matanikau area as a base for attacks on the Marine Lunga defenses, and to destroy any Japanese forces in the area. The Japanese repulsed the Marine attacks. During the action, three U.S. Marine companies were surrounded by Japanese forces, took heavy losses, and barely escaped with assistance from a U.S. Navy destroyer and landing craft manned by U.S. Coast Guard personnel.

In the second action two weeks later, a larger force of U.S. Marines successfully crossed the Matanikau River, attacked Japanese forces and inflicted heavy casualties on a Japanese infantry regiment. The second action forced the Japanese to retreat from their positions east of the Matanikau and hindered Japanese preparations for their planned major offensive on the U.S. Lunga defenses set for later in October 1942 that resulted in the Battle for Henderson Field.

8. Battle of Cape Esperance (11 -12 October)

In the Battle of Cape Esperance, off the northwest coast of Guadalcanal, Rear Admiral Norman Scott’s cruiser-destroyer force TF-64 put one Japanese heavy cruiser and a destroyer on the bottom of Ironbottom Sound, for the loss of one destroyer lost to both enemy and friendly fire during a heroic solo torpedo attack. The light cruiser USS Boise (CL-47) was put out of action by a hit in her 6-inch magazine.

At a cost of 163 lives and one destroyer, Scott inflicted some degree of revenge for the defeat at Savo Island (Aoba, Furutaka, and Kinugasa had comprised three of the five Japanese heavy cruisers at Savo). The results of the battle came as an enormous shock to the Japanese, followed by much recrimination. The fact that the Japanese were so uncharacteristically taken completely by surprise caused the U.S. to learn some wrong lessons about Japanese night-fighting capability, as well as what proper use of radar should be, along with tactical formations (particularly torpedo tactics). This misread would cost the U.S. in later battles. As one U.S. officer at the battle would later comment, Cape Esperance was a three-way battle in which chance was the major victor. Nevertheless, the victory was a huge morale booster for U.S. naval forces in the vicinity of Guadalcanal and for the Marines ashore, albeit short-lived. (For more on the Battle of Cape Esperance, please see attachment H-011-1.)

– Henderson Field Bombardment (13 – 14 October)

The Battle of Cape Esperance prevented the Japanese “bombardment group” from attacking Henderson Field but the “reinforcement group,” which was Scott’s real intended target, had already gone past Cape Esperance and during the night successfully off-loaded hundreds of troops and the first Japanese heavy artillery to reach the island, and then successfully escaped. Even worse was on the night of 13/14 October, two Japanese battleships (Kongo and Haruna) arrived off Guadalcanal, completely by surprise, and fired almost 1,000 14-inch shells into Henderson Field in the most devastating battleship bombardment experienced by any ground troops up to that point in history. Opposed by only four U.S. PT-boats (ineffectively) and concentrating their fire on the airfield, the battleships killed 41 Marines (many aviation and aircraft maintenance personnel).

Wreckage of a Dauntless after the bombardment

More than half the aircraft at Henderson Field were destroyed and many of the rest were damaged to various degrees, and most stores of aviation fuel were destroyed. Although 24 of 42 Wildcats were flyable, only 7 of 39 SBD dive bombers and none of the six TBF torpedo bombers were airworthy.

There were multiple ramifications to follow.

- “The Bombardment” is the real origin of the “Navy abandoning the Marines at Guadalcanal” narrative. The next day—as Brigadier General Roy Geiger, USMC, commander of U.S. aviation forces at Guadalcanal, was noted to exclaim, “I don’t think we have a g**damn navy!”— the destroyer USS Meredith (DD-434) and fleet tug Vireo (AT-144) were caught alone by 38 aircraft from the Japanese carrier Zuikaku while attempting to tow a barge with critical aviation fuel to Guadalcanal. Meredith knocked down three Japanese aircraft, but was hit by 14 bombs and at least three torpedoes, sinking in less than ten minutes; 237 U.S. Sailors from Meredith and Vireo lost their lives as they drifted three days in shark-infested waters before the approximately 100 survivors were rescued.

- Although there is little Vice Admiral Robert Ghormley, Commander of U.S. Forces in the South Pacific Area, could have done to stop the battleship bombardment, it effectively served as the last straw for both U.S. Pacific Fleet Commander Admiral Chester Nimitz, and CNO Admiral Ernest J. King. Both were profoundly dissatisfied by the overall lack of aggressive U.S. Navy action in challenging the frequent runs by the Japanese “Tokyo Express,” which were getting ever more troops and supplies (although not nearly enough of both) onto Guadalcanal, representing a growing threat to the U.S. Marines on the island.

- As a result, Vice Admiral William F. “Bill” Halsey, finally recovered from his bout of debilitating skin rash, arrived at Noumea on 18 October expecting to take over command of the carrier task force (TF-61), was instead handed a sealed envelope that ordered him to relieve Ghormely as Commander of the South Pacific Area. Halsey’s arrival was electrifying, and his aggressive fighting spirit was exactly what was needed at that time.

9. Battle for Henderson Field (23–26 October)

The Battle for Henderson Field, also known as the Battle of Lunga Point by the Japanese was the third of the three major land offensives conducted by the Japanese during the Guadalcanal campaign.

In the battle, U.S. Marine and Army forces, repulsed an attack by the Japanese 17th Army. The U.S. forces were defending the Lunga perimeter, which guarded Henderson Field. Japanese soldiers conducted numerous assaults over three days at various locations around the Lunga perimeter, all repulsed with heavy Japanese losses. At the same time, Allied aircraft operating from Henderson Field successfully defended U.S. positions on Guadalcanal from attacks by Japanese naval air and sea forces.

The battle was the last serious ground offensive conducted by Japanese forces on Guadalcanal. After an attempt to deliver further reinforcements failed during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal in November 1942, Japan conceded defeat in the struggle for the island and began in the utmost secrecy planning to evacuate its remaining forces by the first week of February 1943.

10. Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands (26 October)

(Note: subject of a separate post)

The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October, northeast of Guadalcanal, was the fourth carrier versus carrier battle of the war, and was a victory for the Japanese at an extremely high cost in planes and aviators. In exchange for sinking the carrier USS Hornet(CV-8) and seriously damaging USS Enterprise (CV-6) , the Japanese lost more aircrew than at Coral Sea, Midway, and Eastern Solomons combined. The losses were so severe, particularly amongst senior squadron commanders and flight leaders, that with the exception of the medium carrier Junyo, the Japanese carrier force did not choose to engage again for almost two more years, until June 1944.

With the loss of Hornet and damage to the Enterprise, the U.S. had no operational fleet carriers left in the Pacific. This set the stage for a series of the most brutal and costly surface actions in U.S. naval history.

11. Naval Battle of Guadalcanal (12–15 November)

The decisive engagement in the series of naval battles during the months-long Guadalcanal Campaign was the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, sometimes referred to as the Third and Fourth Battles of Savo Island, the Battle of the Solomons, the Battle of Friday the 13th, or, in Japanese sources, the Third Battle of the Solomon Sea. The action consisted of combined air and sea engagements over four days, most near Guadalcanal and all related to a Japanese effort to reinforce land forces on the island. The only two U.S. Navy admirals to be killed in a surface engagement in the war were lost in this battle.

– Battle of “Friday the 13th” (13 October)

Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan, the commander of a force of five cruisers and eight destroyers (Task Group 67.4) was assigned the mission to interdict a Japanese task group and prevent a second devastating battleship bombardment of Henderson Field and U.S. Marine positions on Guadalcanal. Neither Callaghan, nor Rear Admiral Norman Scott, nor a total of 1,439 American Sailors would survive the incredibly vicious, chaotic, no-quarter, close-quarters nighttime melee with two Japanese battleships, a light cruiser, and 11 destroyers.

By the time the battle was over, of the 13 U.S. ships engaged, two anti-aircraft cruisers (Atlanta (CL-51) and Juneau (CL-52)) and four destroyers (Cushing (DD-376), Laffey (DD-459)(picture), Barton (DD-599), and Monssen (DD-436)) would be sunk. Two heavy cruisers (San Francisco and Portland (CA-33)) and two destroyers (Sterret (DD-407) and Aaron Ward(DD-483)) were seriously damaged. Only the light cruiser Helena (CL-50) and destroyers O’Bannon (DD-450) and Fletcher (DD-445) survived the deluge of battleship shells and “Long Lance” torpedoes with minimal damage or no casualties.

The Japanese lost only two destroyers, but Hiei, one of the two battleships, was so badly battered that she could not steer or clear the battle area, and was sunk the next day by U.S. Navy and Marine aircraft, flying from Henderson Field and USS Enterprise. Most important, Callaghan’s force accomplished its mission and thus keeping Henderson Field operational and maintaining its pivotal role:

- prevented another bombardment

- prevented about 5,000 Japanese reinforcements from reaching the island

- sunk almost all the supplies and ammunition of the 2,000 who did reach

The appalling cost of the battle caused many navy leaders at the time – and many historians since then – to question Admiral Callaghan’s tactical judgement, particularly his integration (or lack thereof) of newer radar on some of his ships. Callaghan’s ships were never designed or intended to duke it out with battleships, nor could the technology of radar be a panacea for decades of avoidance of realistic nighttime training (which would be disastrously demonstrated again at the Battle of Tassafaronga just two weeks later).

Callaghan’s only hope of success was to get as close to the battleships as quickly as possible before opening fire. Whether this was his concept is unknown, because he left no written plan and those who might have known were dead too, but that is indeed what happened. Opening fire sooner only would have given the Japanese battleships more time to find the range before the much lighter U.S. weapons could inflict any serious damage on the more heavily armored battleships. Given the force disparity, there is no realistic outcome in which this battle would have turned out any better for the U.S. with or without more effective use of radar. (For more of the Battle of Friday the 13th, please see attachment H-012-1.)

– Battleship Versus Battleship – 14–15 November

In conjunction with the battle of the night of the 13th, yet another brutal night battle during the following night of 14/15 November turned the final tide of the campaign for Guadalcanal in favor of the United States. In the near-run battle the difference was made by one new American battleship, USS Washington (BB-56).

With the battleship South Dakota (BB-57) on fire and out of action, and the four screening destroyers sunk or crippled, Washington was the only ship left of Rear Admiral Willis “Ching” Lee’s Task Force 64, which entered Iron Bottom Sound the evening of 14 November in a last-ditch effort by Vice Admiral William F. Halsey to halt yet another major attempt by the Japanese to bombard Henderson Field and land more reinforcements on Guadalcanal (it was a last-ditch effort for the Japanese, too).

Lee was the Navy’s foremost flag-level expert on the integration and use of radar, and that knowledge and technology provided the critical edge in turning what could have been a disaster into a decisive victory.

Washington single-handedly took on a Japanese force of one battleship (Kirishima, a survivor of the 13 November battle), two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and nine destroyers. In a matter of minutes, with accurate radar-directed fire, Washington pummeled the Kirishima with between nine and 20 hits (probably 20) by 16-inch shells and over 40 hits by 5-inch shells, which caused Kirishima to sink after midnight.

Washington also hit other Japanese ships with her secondary armament, probably including the destroyer Preston (DD-379). Washington then maneuvered to avoid multiple torpedo attacks. The loss of the Kirishima caused the rest of the Japanese force to withdraw, with the exception of one sinking destroyer.

Disillusioned by the Japanese army’s inability to make any progress against the U.S. Marines and stunned by the loss of two battleships, the Japanese navy decided to limit further action to making “Tokyo Express” supply runs using destroyers. It would never again commit cruisers or battleships (or aircraft carriers) to the waters around Guadalcanal.

The action between Washington and Kirishima was the only one-on-one battleship action in the Pacific War, and the first of only two battleship-versus-battleship actions in the Pacific (the other was at the Battle of Surigao Strait in October 1944).

After the battle, Washington’s skipper, Captain Glenn Davis, made a profound observation: “Radar has forced the Captain or OTC to base a greater part of his actions on what he is told rather than what he can see.” Naval warfare had just been revolutionized. (For more on the Battle of 14-15 Nov, please see attachment H-012-4.)

12. Battle of Tassafaronga (Night of the Long Lances) (30 November)

On the night of 30 November/1 December 1942, a U.S. force of five cruisers and six destroyers (Task Force 67) under the command of Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright, ambushed a Japanese “Tokyo Express” run consisting of eight destroyers (six of which were encumbered by hundreds of supply barrels) under the command of Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka. Although the U.S. was armed with intelligence that the Japanese were coming, made excellent use of the new SG radar technology aboard U.S. flagships that detected the Japanese first (at 23,000 yards), had carefully absorbed and incorporated numerous lessons from the previous night battles in Iron Bottom Sound, possessed overwhelming advantage in firepower, and opened fire first, the result was still one of the worst debacles in the history of the United States Navy.

At Tassafaronga, for the loss of one destroyer, the Japanese sank the heavy cruiser USS Northampton (CA-26) and grievously damaged the heavy cruisers Minneapolis (CA-36), New Orleans (CA-32), and Pensacola (CA-24). The three cruisers were saved only by extraordinarily heroic and determined damage-control actions by their crews and by the fact that six of the Japanese destroyers did not have their torpedo reloads aboard, preventing them from picking off the U.S. cripples. All three damaged cruisers would be out of action for over a year. U.S. casualties included 395 Sailors killed and 153 wounded. The result was arguably the most successful surface torpedo attack in history.

Extensive recriminations occurred following this battle. Rear Admiral Wright’s career as a combat commander was over within days. Nevertheless, the one lesson that U.S. Navy leaders stubbornly refused to learn was that the Japanese Type 93 Oxygen Torpedo (“Long Lance”) was significantly superior, despite the pre-war intelligence (which had been ignored), and despite the late Rear Admiral Norman Scott’s report following the Battle of Cape Esperance. More U.S. ships would fall to the Long Lance in battles in the Central Solomon Islands in 1943 and 1944 as a result of this U.S. failure to understand the enemy. For more on the Battle of Tassafaronga, please see attachment H-013-1.

13. Battle of Mount Austen, the Galloping Horse, and the Sea Horse, (Battle of the Gifu) (15 December 1942 – 23 January 1943)

The Battle of Mount Austen, the Galloping Horse, and the Sea Horse, part of which is sometimes called the Battle of the Gifu, was primarily an engagement between United States and Imperial Japanese forces in the hills near the Matanikau River. The U.S. forces were now under the overall command of U.S. Army general Alexander Patch.

In the battle, U.S. soldiers and Marines, assisted by native Solomon Islanders, attacked Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) forces defending well-fortified and entrenched positions on several hills and ridges. The most prominent hills were called Mount Austen, the Galloping Horse, and the Sea Horse by the Americans. The U.S. was attempting to destroy the Japanese forces on Guadalcanal and the Japanese were trying to hold their defensive positions until reinforcements could arrive.

Both sides experienced extreme difficulties in fighting in the thick jungles and tropical environment that existed in the battle area. Many of the American troops were also involved in their first combat operations. The Japanese were mostly cut off from resupply and suffered greatly from malnourishment and lack of medical care. After some difficulty, the U.S. succeeded in taking Mount Austen, in the process reducing a strongly defended position called the Gifu, as well as the Galloping Horse and the Sea Horse. In the meantime, the Japanese decided to abandon Guadalcanal and withdrew to the west coast of the island. From that location most of the surviving Japanese troops were successfully evacuated during the first week of February 1943.

14. Operation Ke and the Battle of Rennell Island – Jan -Feb 1943

With the loss of a heavy cruiser and three more heavy cruisers put out of action for months at Tassafaronga, the U.S. stopped sending large ships into Ironbottom Sound, leaving the PT-boat squadrons (Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla One) based at Tulagi to oppose further efforts by the Japanese “Tokyo Express” to get supplies to their troops on Guadalcanal. On the next Tokyo Express run after Tassafaronga, on 3 December, the U.S. PT-boats accomplished the same thing as the U.S. cruisers had (preventing the resupply effort) at far less cost. The Japanese only attempted one more supply run, this one more successful, on 11 December.

In January, U.S. surface ships began to venture for the first time up “The Slot” toward the central Solomon Islands to bombard a Japanese airfield being constructed (and soon abandoned) on Munda.

At end of January, the Japanese got in two more severe blows on the U.S. Navy. The Japanese deployed two elite squadrons of G4M Betty bombers that had been extensively trained to conduct night torpedo attacks, and on the night of 29 January, the Bettys hit the heavy cruiser USS Chicago (CA-29)—survivor of the Battle of Savo Island—with two torpedoes near Rennell Island, southwest of Guadalcanal. Despite heavy losses, Japanese bombers hit the cruiser with four more torpedoes, sending her to the bottom, and also damaged the destroyer La Vallette (DD-448) with a torpedo. On 1 February, Japanese dive bombers caught the destroyer De Haven (DD-469) off the north shore of Guadalcanal, hitting her in the forward magazine and causing a massive explosion that sent her to the depths of Ironbottom Sound with most of her crew, including her skipper, Commander Charles Tolman.

By late January 1943, all the intelligence indicators strongly pointed to another major Japanese effort to retake Guadalcanal similar to the pushes in September, October, and November that had all resulted in horrific battles ashore, at sea, and in the air. In response to the Japanese build-up at Truk and Rabaul, Admiral Nimitz committed virtually the entire operational U.S. Pacific Fleet to Vice Admiral Halsey’s South Pacific Force. Both operational carriers (the repaired USS Enterprise and USS Saratoga, three modern battleships, additional cruisers (including three new-construction Cleveland-class light cruisers) waited south of Guadalcanal to counter, or preferably ambush, the reconstituted Japanese carrier force when it came.

Three times in the first week of February 1943, a force of over 20 Japanese destroyers (the “Reinforcement Group”) steamed to Guadalcanal, fighting off long-range U.S. air attacks at dusk, and on the first night, engaging in a vicious fight with U.S. PT-boats that resulted in the loss of three PT-boats and one Japanese destroyer. Intelligence suggested the Japanese had landed at least a regiment of troops on the island (which wasn’t much compared to U.S. troop strength that would soon reach 50,000).

It wasn’t until 7 February that advancing U.S. Army troops realized that they were only being opposed by Japanese troops who couldn’t walk, armed only with a rifle, poison pills, and orders to do what they could to slow down the U.S. troops. Only then did the Americans realize they’d been had by one of the most effective deception operations by any side in the war – Operation Ke, in effect the Japanese Dunkirk, was an evacuation, not a reinforcement. The Japanese successfully withdrew over 10,000 troops without significant loss from the island, albeit leaving behind over 20,000 dead and a handful of dying (and another 10,000 who had been previously lost at sea, including about 3,800 Japanese Imperial Navy sailors.)

For more on the end of the Guadalcanal campaign, please see attachment H-015-2

Conclusion

With the Battle of Rennell Island and the end of Operation Ke, the Guadalcanal campaign was effectively over (although the last Japanese holdout on the island didn’t surrender until October 1947). After six months of some of most vicious combat in the history of naval warfare, the increasingly strong U.S. Navy was in possession of the waters around the eastern Solomons.

The cost to both sides had been extremely heavy, and at sea and in the air roughly even. On land, Japanese army casualties greatly exceeded those of the U.S. Marines and U.S. Army. The Battle of Midway stopped the Japanese advance, but the Guadalcanal Campaign was the true turning point of the war in the Pacific. The cost to the U.S. Navy included two aircraft carriers, five heavy cruisers (plus one Australian heavy cruiser), two light cruisers, 15 destroyers, three destroyer-transports, and one transport, plus about 615 aircraft (of all services, including 90 carrier-based) and just under 5,000 Sailors killed (including 130 naval aviators and air crew, plus 92 Australian and New Zealand naval personnel, but not including 49 Marines embarked aboard ship). Almost three times as many American Sailors died at sea defending Guadalcanal as American Marines and Army personnel died on it. During the brutal six-month campaign, the U.S. Navy “abandoned” the U.S. Marines for a grand total of four days, yet that myth lives on.

Post Script

There were twenty awards of the Medal of Honor resulting from the Guadalcanal campaign including one Marine general and two Navy admirals, and the only award in history to a member of the Coast Guard.

The record of valor displayed by the U.S. Navy in the Battle of Friday the 13th was astounding. Rear Admirals Callaghan and Scott were both awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor (Scott was actually killed by “friendly” fire). Three Medals of Honor were awarded to crew on San Francisco, who fought on after the most senior officers were all killed: Lieutenant Commander Herbert Schonland, Lieutenant Commander Bruce McCandless, and (posthumously) Boatswain’s Mate First Class Reinhardt Keppler. San Francisco received a Presidential Unit Citation, as did Laffey, Sterett, and O’Bannon.

The crew of San Francisco alone accounted for 32 Navy Crosses (22 posthumous) and 21 Silver Stars, and there were more on other ships. The commanding officers of all 13 ships in the battle were awarded a Navy Cross, four posthumously. At least 28 U.S. Navy destroyers and destroyer-escorts were named in honor of those brave Sailors who fell in this most epochal battle in U.S. Navy history (one of these, USS Harmon (DE-678) – was the first warship named in honor of an African-American, Mess Attendant First Class Leonard Roy Harmon, killed on San Francisco). USS The Sullivans (DD-537 and DDG-68) were named after the five Sullivan brothers, all lost aboard Juneau.

As in the Battle of Friday the 13th, the ferocity of the 14-15 November engagement was such that every commanding officer of the six U.S. ships involved was awarded a Navy Cross, two posthumously. Total U.S. personnel losses in the battle were 242 killed in action and 142 wounded.

A note on sources

There are multiple books, studies and websites devoted to the Guadalcanal Campaign. This piece was based on finding the best overall summaries and then shortening them even further. Some combining was necessary so as to insure that the inter-dependency of land, sea and air operations stood out. Much use was made of Naval History and Heritage Command and the H-Grams.