Blown Slick Series #13 Part 9

On Land, on Sea, in the Air – Introduction

9 February, 1943

Major General Alexander Patch, USA, Commander, Guadalcanal to Vice Admiral William Halsey, Jr., USN, Commander, South Pacific Area,

TOTAL AND COMPLETE DEFEAT OF JAPANESE FORCES ON GUADALCANAL EFFECTED 1625 TODAY… AM HAPPY TO REPORT THIS KIND OF COMPLIANCE WITH YOUR ORDERS … ‘ TOKYO EXPRESS ’ NO LONGER HAS TERMINUS ON GUADALCANAL .

Under extreme secrecy, on the nights of 1, 4, and 7 February 1943, the Japanese had completely fooled the ground and sea commanders, pilots, ships and PT boats of the U.S. South Pacific Forces and evacuated the 10,652 remaining of 36,000 soldiers from Guadalcanal. Operation KE was indeed a Pacific Dunkirk. The Guadalcanal Campaign was over.

This series is about the introduction of the aircraft carrier into naval warfare in the four 1942 carrier vs. carrier battles. Two of those battles – The Battle of the Eastern Solomons and The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands – were part of the Guadalcanal campaign. Tactically similar in many ways to the Coral Sea and Midway battles, the multi-faceted warfare context (land, sea, and both sea and land-based air) created a much different dynamic than the earlier battles. While this discussion of the Guadalcanal battles will not go into any great detail on the land and sea contests, the story of the carriers cannot be told without the broader context.

The battle for Guadalcanal had been a very close run thing. Only on the morning of 8 Feb. 1943 did U.S. Army forces realize that the recent Tokyo Express runs were evacuation runs and not the next step in reinforcing Japanese troops for a next attempt to retake the airfield and island. Indeed the cruiser USS Chicago had been sunk on 30 Jan., the destroyer USS De Haven sunk on the first of Feb., along with three PT boats and eighteen Cactus Air Force planes lost over the next several days.

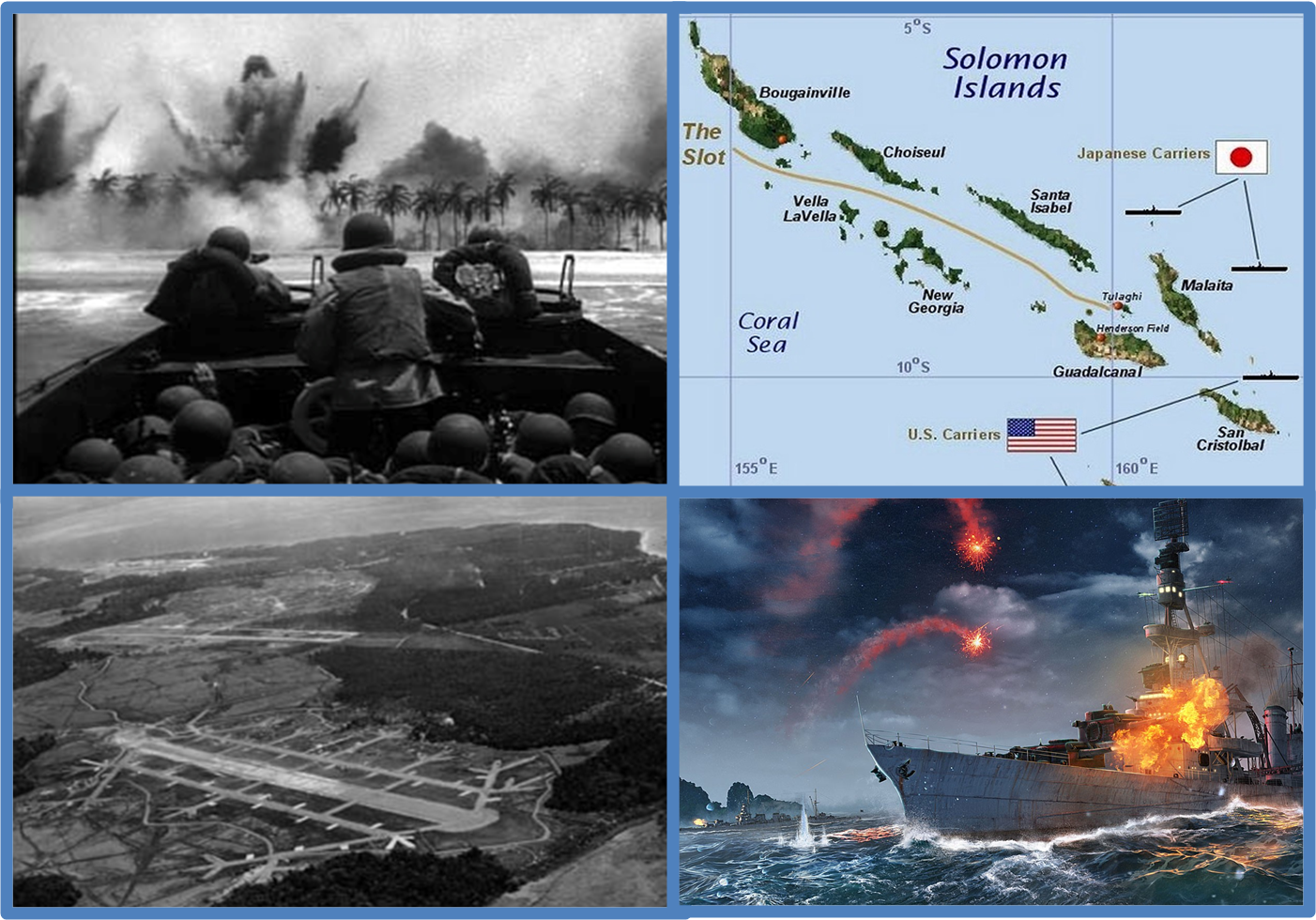

The Guadalcanal Campaign or Operation Watchtower had begun six months earlier on 7 August 1942 with an amphibious assault on the island and across the sound at the Tulagi anchorage. With minimal initial opposition the Japanese immediately began the effort to retake the island and its airfield (to be named Henderson Field in honor of a Marine aviator killed in defense of Midway).

Given the golden opportunity of Midway, Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) Admiral Ernest King, had directed Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet (CinCPac) Chester Nimitz to begin preparation to go on to the attack. The haste in putting Operation Watchtower together would prove problematic on many levels not the least of which was that this tasking was completely new – none of the commanders knew how to put it all together, from logistics, to air support of ground forces with long term land, sea, and air opposition, to night battles at sea.

Known certainly for the effort and courage of the marines and soldiers under General Archer Vandergrift in the extremely difficult island jungle conditions, the Guadalcanal Campaign encompassed not only three major land battles, but also seven large naval battles (five night-time surface actions and two carrier battles), with almost daily aerial battles including both Japanese and U.S. land and sea-based air. Henderson Field was under daily air attacks and nightly bombardment from the sea by Japanese destroyers. Indeed it was not until the decisive Naval Battle of Guadalcanal in mid November that the last Japanese attempt to bombard Henderson Field from the sea and to land with enough troops to retake it was turned back that U.S. victory was other than tenuous.

From Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal by James D Hornfischer

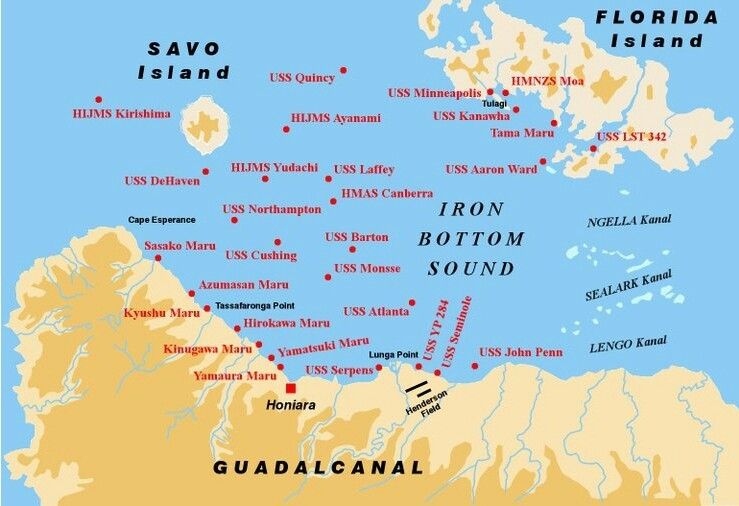

“The American landings on Guadalcanal developed into the most sustained and vicious fight of the Pacific war … the nickname the Americans coined for the waters that hosted most of the carnage, Ironbottom Sound, suited the startling scale of destruction: The U.S. Navy lost twenty-four major warships; the Japanese lost twenty-four. Aircraft losses too, were nearly equal: America lost 436, Japan 440 . The human toll was horrific. Ashore, U.S. Marine and Army killed in action were 1,592 (out of 60,000 landed ). The number of Americans killed at sea topped five thousand . Japanese deaths set the bloody pace for the rest of the war, with 20,800 soldiers lost on the island and probably 4,000 sailors at sea…

As its principal players would admit afterward, the puzzle of victory was solved on the fly and on the cheap, in terms of resources if not lives. The campaign featured tight interdependence among warriors of the air, land, and sea. For the infantry to seize and hold the island, ships had to control the sea. For a fleet to control the sea, the pilots had to fly from the island’s airfield. For the pilots to fly from the airfield, the infantry had to hold the island.

That tripod stood only by the strength of all three legs. In the end, though, it was principally a navy’s battle to win. And despite the ostensible lesson of the Battle of Midway, which had supposedly crowned the aircraft carrier as queen of the seas, the combat sailors of America’s surface fleet had a more than incidental voice in who would prevail. For most of the campaign, Guadalcanal was a contest of equals, perhaps the only major battle in the Pacific where the United States and Japan fought from positions of parity. Its outcome was often in doubt.”

There are a multitude of reasons for the great historical interest in the Guadalcanal campaign:

- the combination of air, land, and sea operations in the face of significant deficiencies in intelligence, doctrine, and materiel

- the relative overall equality of the forces (after the carrier Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands both sides were forced to retrench – the U.S. because of the loss of carriers, the Japanese through loss of aircraft and pilots)

- the unusually large number (for World War I or II) of surface-to-surface naval battles. (although many think of Guadalcanal in terms of the land battles, there were more naval battles fought off the island in six months than the British Royal Navy fought in all of World War I)

- the heightened manifestation of “fog of war” on both sides due to lack of meaningful intelligence, uncertain reconnaissance, bad weather, and the night operations of the Tokyo Express, all coupled with horrible communications

- the sharp contrast between day and night operations, particularly in light of Japanese training for night surface operations

- the value and dynamics of land-based air on both sides

- the learning necessary for both land and sea-based air in support of amphibious operations and their sustainment (bomber pilots were trained to attack ships not for close air support of ground troops in contact with the enemy)

- the first use coupled with miss-use by the U.S. with seaborne radar

- the negative dynamics created by the need felt to protect the carriers compared with the protection of the Marine ground forces exacerbated further by the Japanese air and night sea bombardment of Henderson Field and the Marine “sense of abandonment by the Navy.” Note: There were 5,041 U.S. Navy sailors killed in action in the campaign, compared to 1,592 U.S. Marines and soldiers which increases the unfairness at the relative historical and popular treatment of the two sides of this particular story.

- and then finally – just how hard this all turned out to be for both sides. The most striking thing about this is the virtual equality of the results — 24 ships on each side, with comparable tonnage. However, the meaning of this was very different for each side.

As the series continues with discussion of the Guadalcanal campaign and the last carrier battles before the final CV battle – the Marianas Turkey Shoot at the Philippine Sea in 1944 – it is worth highlighting how much the rough parity of carrier forces of the two sides contributed to the protracted nature of the overall bloody struggle for the island. The next post will provide short summaries of the major battles for context as we proceed.