Testimony of Pilot# 11

An airplane is just a bunch of sticks and wires and cloth, a tool for learning about the sky and about what kind of person I am, when I fly. An airplane stands for freedom, for joy, for the power to understand, and to demonstrate that understanding. Those things aren’t destructible.

Nothing by Chance, Richard Bach

SPAD XIII cockpit (c. 1918) as flown by Eddie Rickenbacker in the 94th AERO Squadron and the F-35 Lightning Joint Strike Fighter “glass” cockpit (2018)

Once I determined to make Trap’s story of the F4U Corsair development and test the centerpiece of Chapter Two, it wasn’t hard to pick other aviators and their stories with similar experiences in the advancement of aviation – problem was who to leave out. Three in particular were difficult to exclude (Rickenbacker, Doolittle,Yeager).

But in the parsing of stories I found some intriguing pictures of the cockpits of the aircraft used to push the ole envelop. So here in keeping with Chapter One’s pictures as stories here is an offering of history via the cockpit. TINS:

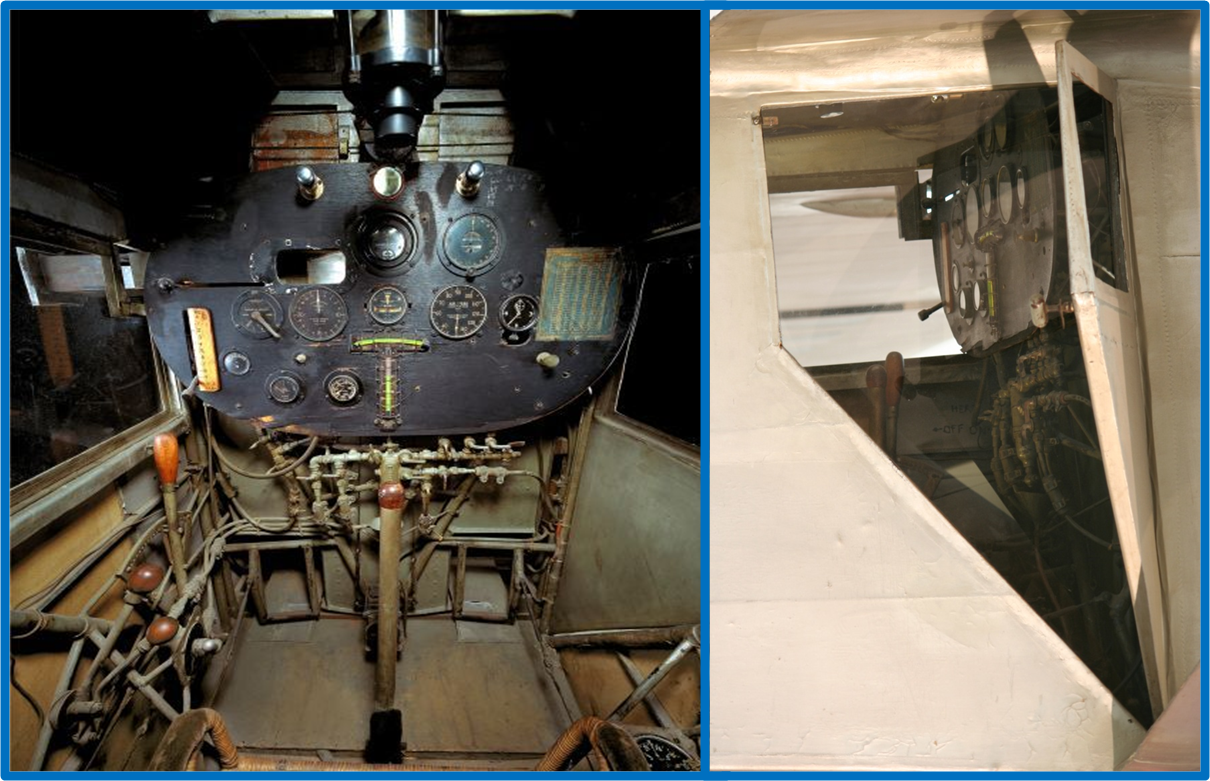

Lindbergh’s The Spirit of St. Louis

Lindbergh … declared before his famous Atlantic flight that “aviation will never amount to much until we learn to free ourselves from mist.”1 It was too true. Since the inception of flight, aviation had been used for war, to carry mail, and for barnstorming performances and sport racing. But for ordinary civilians airplanes remained, basically, a novelty. Even though airplane cockpits were beginning to be enclosed to make more comfortable cabins, mass transportation was left to ships, trains, and automobiles, because without the ability to fly in fog, blizzards, and other heavy weather—flying “blind” was the expression—airlines could guarantee no regular schedules, and without dependable schedules, as Lindbergh pointed out, they were not attractive for either freight or passengers.

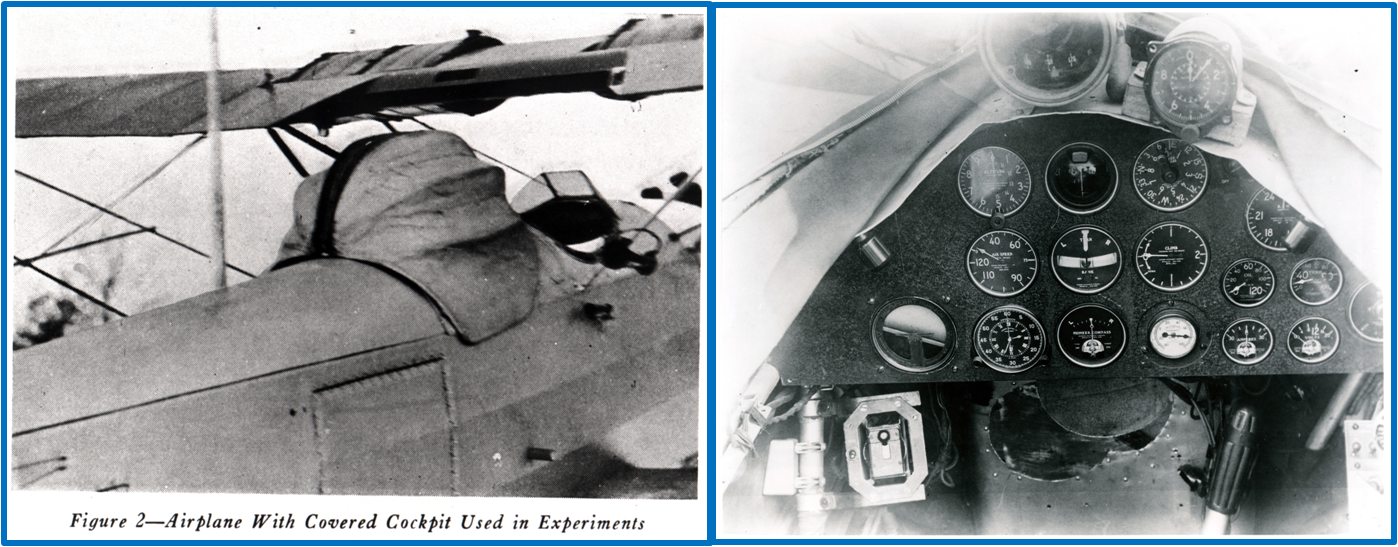

Doolittle’s NY-2 Husky blind flight cockpit set-up

It was decided that Jimmy Doolittle should do an “official” blind flight, meaning that everything, every move, would be thoroughly measured and recorded. On the test day the heaviest fog had begun to disperse but there was just enough left. With the hood over the cockpit “tightly closed,” Doolittle taxied out onto the grass runway and let the engine rev while he once more adjusted the directional gyroscope to the magnetic compass heading and set the altimeter at zero.

March 1929 …When he was satisfied he had full power on, Doolittle let go the brakes and roared off westward. (At Guggenheim’s insistence another pilot was put in the forward cockpit but he kept his hands off the controls the entire flight.) Leveling out at 1,000 feet, Doolittle flew five miles, then made a series of 90-degree left turns; the last put him in the landing pattern for the west runway. The two vibrating reeds were humming left and right in the cockpit, homing him in to the Mitchel Field beacon. Whenever he veered off course, the reed in that direction would vibrate more, telling him to steer the other way. If he kept the reeds vibrating at an equal rate he knew he was flying on a direct path to the runway. Slowly descending until his new altimeter registered precisely 400 feet, he leveled out and picked up the local runway beam that guided him down, 200 feet, 100 feet, until he crossed thirty feet above the fence at the end of the runway and then glided to a touchdown, rolled, settled back on the tail skid, and came to a stop. There was uproarious cheering and applause as everyone rushed to the plane. Guggenheim joyfully pulled back the hood, revealing Doolittle with a vexed expression because he thought he’d made a sloppy landing. “What happened to the fog?” he asked, looking around.

Japanese A6M Zero and Trap’s USN/USMC F4U Corsair

With first flight in April 1939 the Zero or Zeke is considered to have been the most capable carrier-based fighter in the world when it was introduced early in World War II. The Corsair was designed and operated as a carrier-based aircraft, and entered service in large numbers with the U.S. Navy in late 1944 and early 1945. It quickly became one of the most capable carrier-based fighter-bombers of World War II. Naval aviators achieved an 11:1 kill ratio and some Japanese pilots regarded it as the most formidable American fighter of World War II. Notice the more populated cockpit and note that later jet a/c would still be similar.

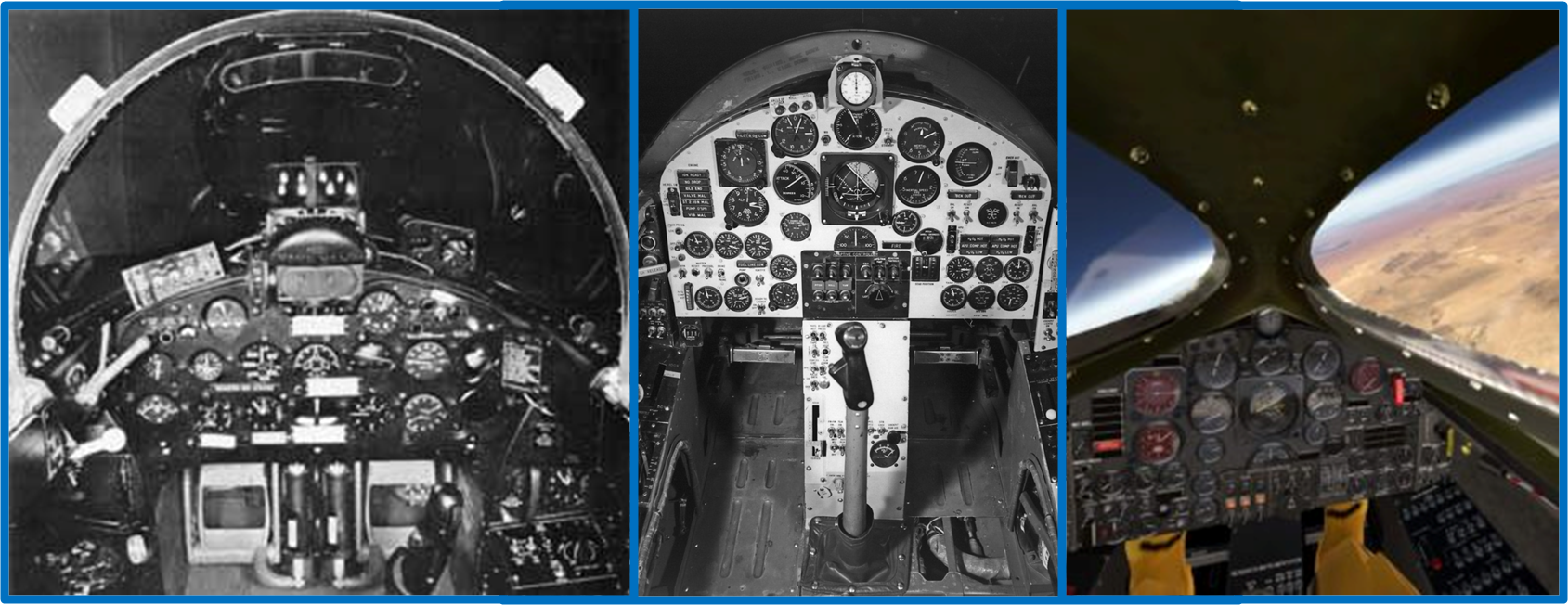

Yeager’s Bell X-1

Conceived during 1944 and designed and built in 1945, it achieved a speed of nearly 1,000 miles per hour (1,600 km/h; 870 kn) in 1948. The X-1, piloted by Chuck Yeager, was the first manned airplane to exceed the speed of sound in level flight and was the first of the X-planes, a series of American experimental rocket planes (and non-rocket planes) designed for testing new technologies.

Armstrong’s F9F-5 Panther and X-15

Notice that the instrumentation of the Panther that Neil Armstrong flew in Korea seems more complex than that of the X-15 experimental rocket plane. Despite designed and designated a fighter, the straight wing F9F-5 was no match for the swept wing North Korean MiG 15. Yet on November 18, 1952 Lt.. Royce Williams, in an exhausting 35 minute dogfight against 7 Soviet MiGs, became the only American Aviator to single-handedly shoot down 4 Russian MiGs in a single sortie.For the first time in history, Soviet pilots secretly flew against NATO and U.S. forces. His heroic actions were kept classified for nearly fifty years. Post- Cold War, the Russian government confirmed the loss of the 4 MiG-15s and disclosed the names of the four pilots he shot down.

With minor modifications other than adding swept wings this is the Navy advanced training aircraft – now named the Cougar – myself and many others flew to advance to being designated Naval Aviators.

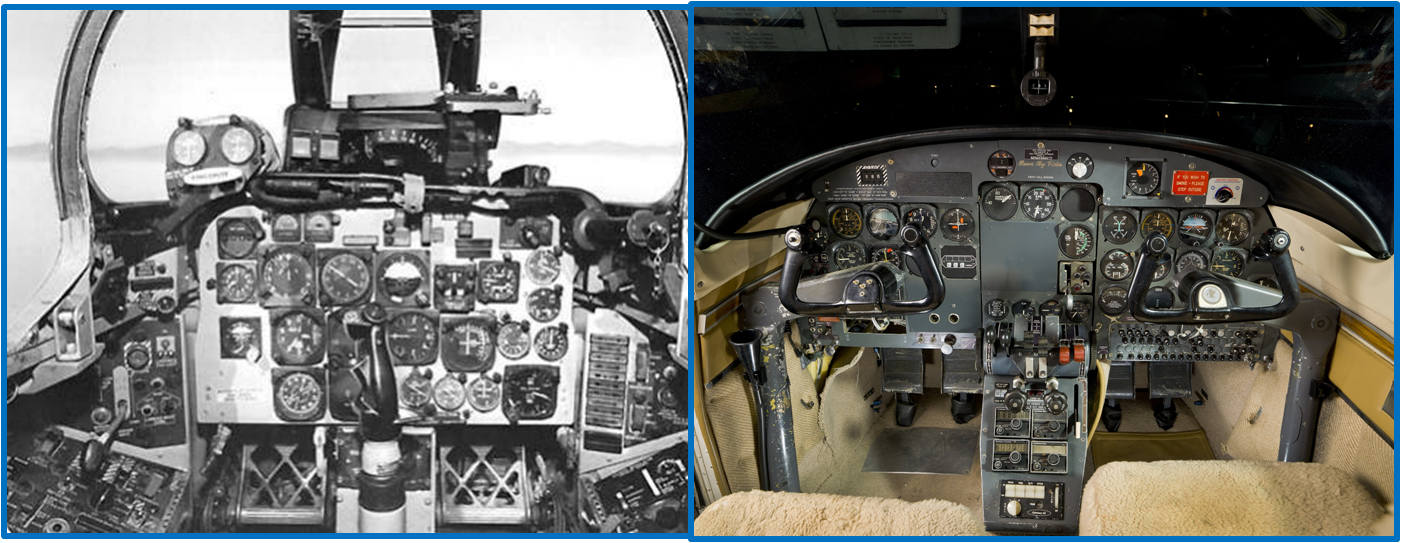

Hoover’s F-100 Super Sabre and Shrike Commander

After a demonstration of aerobatic capability by Bob Hoover, the Air Force selected the F-100 for the Thunderbird Flight Demonstration team. Note the differences between the cockpit of the Aero Shrike Commander, one model of light twin piston-engined and turboprop business aircraft originally built in the late 1940s. The Shrike was structurally limited to 4G’s yet Hoover performed similar aerobatic routines in both aircraft.

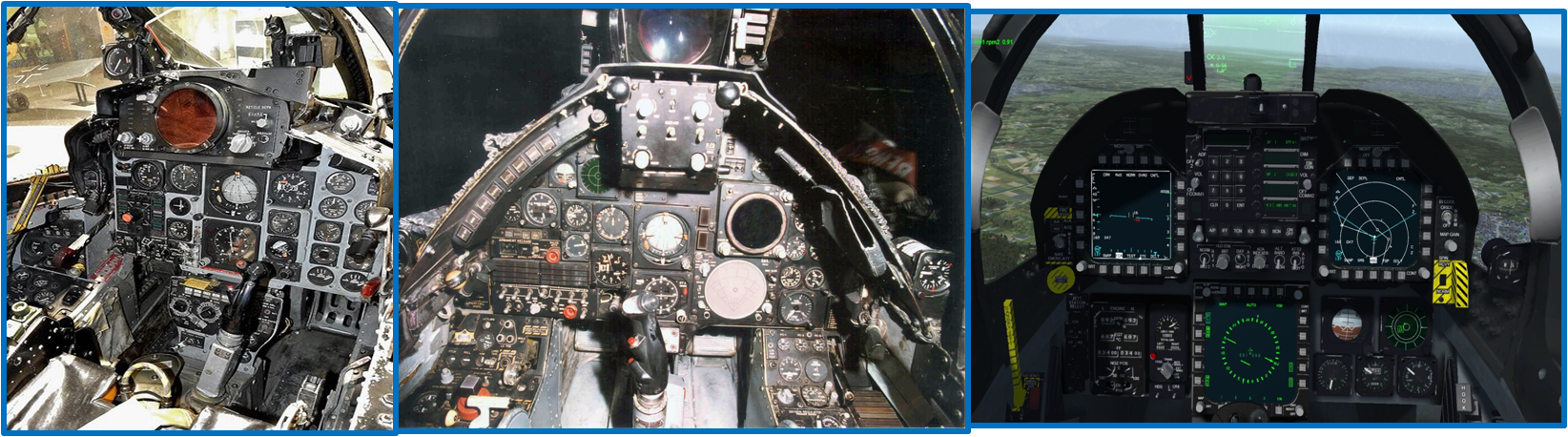

F-4 Phantom, A-7 Corsair II, and F/A-18 Hornet

For the Vietnam war, the F-4 Phantom was a work horse for the Navy, Marines and Air Force while the A-7A/B/C/E Corsair II replaced the A-4 Skyhawk as the Navy’s primary carrier light attack aircraft, and the A-7D was adopted as the “Sandy” replacement for pilot rescue missions by the Air Force. The FA-18 Hornet was selected as a multi-mission aircraft to replace both the F-4 and A-7. Along with the Hornet, the a/c that followed after Vietnam – F-15, F-16, FA-18 – brought many new technological aspects, one most noticeable, the “glass” cockpit and digital vs. analog instrumentation.

Eileen Collins Space Shuttle Discovery

The orbiter crew cabin consisted of three levels: the flight deck, the mid-deck, and the utility area. The uppermost of these was the flight deck, in which sat the Space Shuttle’s commander and pilot, with up to two mission specialists seated behind them. The mid-deck, which was below the flight deck, had three more seats for the rest of the crew members.

The Space Shuttle orbiter resembled an airplane in its design, with a standard-looking fuselage and two double delta wings, both swept wings at an angle of 81 degrees at their inner leading edges and 45 degrees at their outer leading edges. A combination rudder and speed brake was attached at the trailing edge of the vertical stabilizer. There were four elevons mounted at the trailing edges of the delta wings and these, along with a movable body flap located underneath the main engines, controlled the orbiter during later stages of descent through the atmosphere and landing. Overall, the Space Shuttle orbiter was roughly the same size as a McDonnell Douglas DC-9 airliner.

Entering the Arena -1918 – > 2018

Closing Note: Seat of the pants flying incorporates use of the eyes, ears, maybe your stomach, how your rear feels in the seat during maneuvers, and invariably relies incorrectly on the inputs of your inner ear. As Lindbergh, Doolittle and Rickenbacker understood, the inability to fly in any conditions but clear air mass was a severe limiter on aviation progress. The instruments, both for the monitoring of the “flying” aspects and the engine performance, were crucial for both military and commercial use.

While they might not have been able to quite visualize the SR-71 or space shuttle, those early pilots and engineers moved the ball well down the road in a time and process that may never be duplicated.

Yet, as instructive as the evolution of the cockpit is as a metric of advancement in the air, it is doubtful they could have foreseen one of the most telling characteristics in the 100 years represented by the opening picture of the sparce SPAD XIII cockpit and the F-35 glass cockpit – the transition from a leather helmet and goggles to the $400k helmet and visor system of the Joint Strike Fighter linked with a/c sensors and the cockpit displays.

transition from a leather helmet and goggles to the $400k helmet and visor system of the Joint Strike Fighter linked with a/c sensors and the cockpit displays.

Eddie Rickenbacker had no heads up display (HUD), but then neither does the JSF pilot – its all on his visor.

And so this post closes with the headgear of the day matching the opening picture. TINS.