Blown Slick Series #13 Part 16 (1/3)

Thus begins the day of 23 August, 1942 – Battle of the Eastern Solomons [24–25 August 1942]

At breakfast Fletcher read a special Cincpac Ultra message advising that the “Orange striking force” of two Shokaku-class carriers, two fast battleships, and four heavy cruisers was now “indicated” to be “in or near Truk area,” and thus not nearer to Cactus than one thousand miles. “In Truk-Rabaul area” was “Cinc Second Fleet” with “possibly” two fast battleships and “definitely” four heavy cruisers. This valuable intelligence, however, failed to answer the prime question of when the assault on Guadalcanal might come. With the Japanese carriers so distant, such a move now seemed unlikely for several days.

John B. Lundstrom, Black Shoe Carrier Admiral: Frank Jack Fletcher at Coral Sea, Midway & Guadalcanal . Naval Institute Press.

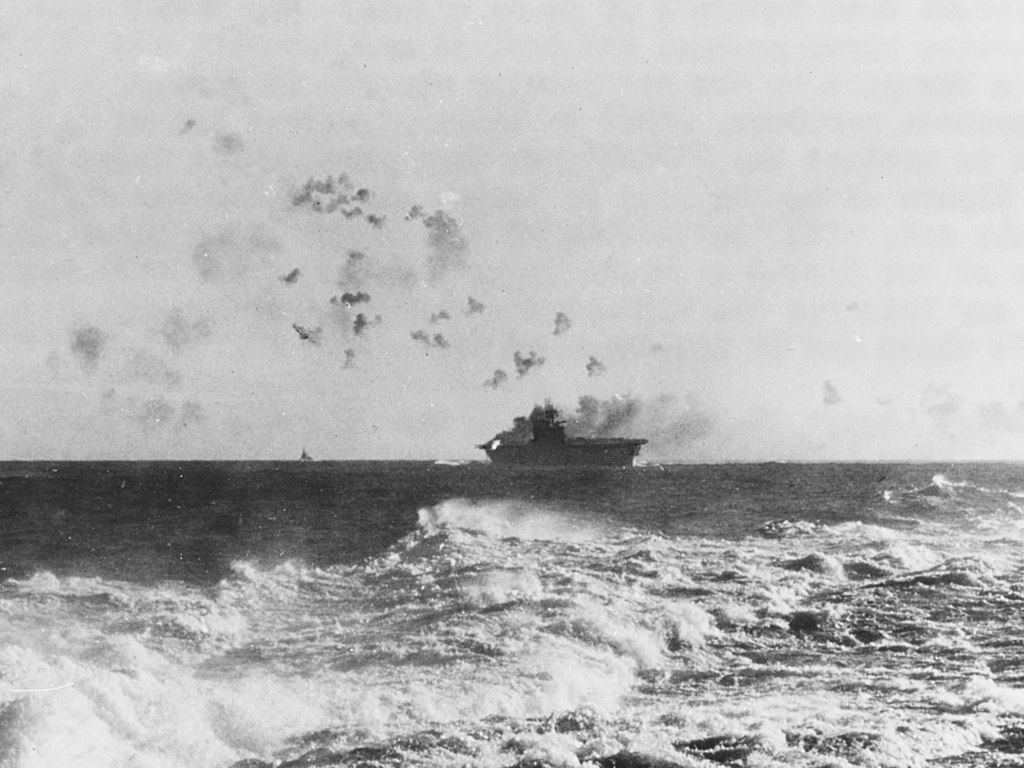

The Enterprise under attack around 4;30 in the afternoon of the 24th by the Japanese aircraft from carriers 1000 miles away AM of the 23rd?

Blindman’s Bluff

The battle of the Eastern Solomons (24-25 August 1942) was the second battle in the series of six naval actions linked to the fighting on Guadalcanal and the third of four carrier vs. carrier battles in 1942.

Remembered Sky introductory remarks

Providing this discussion of the third 1942 carrier battle has been more difficult than the stories for the rest of the series as follows:

- The battle in toto had numerous events occurring simultaneously at several locations making following the battle flow and relations of events very difficult.

- This “messyness” and breadth of the battle has made the historical telling of the story (my resources) in any degree of completeness rather lengthy – books or at minimum multiple chapters. (Telling and then researching of the Battle of Midway was much more straight forward.)

- No senior commander/decision maker for either the U.S. or Japanese had more than minimal situational awareness (SA) of the battle.

The formal definition of SA is broken down into three segments: perception of the elements in the environment, comprehension of the situation, and projection of future status

Intelligence on the enemy was either non-existent or worse, very misleading (Note the opening quote). There was as much searching as fighting and communications back to decision makers was horrible. In short the discussion’s title – Blindman’s Bluff

Setting the Stage

Between 15 and 20 August, U.S. carriers covered the delivery of fighter and bomber aircraft to the newly opened Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. This small, hard-won airfield had become a critical point in the entire island chain, and both sides considered that control of the airbase offered control of the local airspace. In fact, the airfield and the aircraft based there would become the major limiting factor for the movement of Japanese forces in the Solomon Islands and in the attrition of Japanese air forces in the South Pacific Area. And thus, allied control of Henderson Field became the key factor in the entire battle for Guadalcanal.

Surprised by the Allied offensive in the Solomons, after their first small-scale counterattacks on Guadalcanal had failed the Japanese began to move reinforcements onto the island with a force of fast transports, cruisers and light cruisers under Rear-Admiral Raizo Tanaka. Tanaka’s force soon became known to the Americans as the ‘Tokyo Express’ and it would continue to operate for most of the Solomon Islands campaign. Tanaka’s first run was a success, and 815 men were landed on Guadalcanal on the night of 18-19 August but over aggressiveness of the Ichiki commanded troops caused their quick loss in battle.

When news of the Army’s failure reached Truk, it supposedly “shook Yamamoto.” He immediately began planning aboard the super battleship Yamato with task force commanders Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo and Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo, Yamamoto directed the Combined Fleet to gather its considerable assets and head south to confront what was now clearly understood as a significant commitment of American force. He drew up a complex and powerful order of battle. Down from Truk, into the seas east of the Solomons chain, would steam four separate combat task forces: 1) a Striking Force under Nagumo with the large carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku and their escorts; 2) Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe’s Vanguard Group, with the battleships Hiei and Kirishima, three heavy cruisers, a light cruiser, and six destroyers; 3) the Diversionary Group, consisting of the light carrier Ryujo, a cruiser, and two destroyers; and 4) the Support Group, with the old battleship Mutsu, a seaplane tender, and four destroyers. In addition, the 17th Army decided to send down the remaining fifteen hundred men of Ichiki’s regiment. An additional thousand Japanese marines—a Special Naval Landing Force—were embarked in three transports escorted by eight destroyers of Admiral Tanaka’s Destroyer Squadron 2. The Japanese carriers would operate east of the Slot, with intent to attack and destroy their American carrier counterparts, then turn in support of Tanaka’s landing force. This Japanese force nearly rivaled in combat power the group sent to seize Midway.

In summary, The counteroffensive, had the goal of driving the Allies out of Guadalcanal and Tulagi and the additional objective of destroying Allied warship forces in the South Pacific area, specifically the U.S. carriers.

On 16 August, a convoy of three slow transport ships loaded with 1,411 Japanese soldiers from the 28th “Ichiki” Infantry Regiment, as well as several hundred naval troops from the 5th Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF), departed the Japanese base at Truk Lagoon and headed towards Guadalcanal. On 21 August, the rest of the Japanese naval force departed Truk, heading for the southern Solomons. .

On 16 August, a convoy of three slow transport ships loaded with 1,411 Japanese soldiers from the 28th “Ichiki” Infantry Regiment, as well as several hundred naval troops from the 5th Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF), departed the Japanese base at Truk Lagoon and headed towards Guadalcanal. On 21 August, the rest of the Japanese naval force departed Truk, heading for the southern Solomons. .

Finally, a force of about 100 IJN land-based bombers, fighters, and reconnaissance aircraft at Rabaul and nearby islands were positioned for operational support. Nagumo’s main body positioned itself behind the “vanguard” and “advanced” forces in an attempt to more easily remain hidden from U.S. reconnaissance aircraft.

The plan dictated that once U.S. carriers were located, either by Japanese scout aircraft or an attack on one of the Japanese surface forces, Nagumo’s carriers would immediately launch a strike force to destroy the U.S. carriers. With the carriers destroyed or disabled, Abe’s “vanguard” and Kondo’s “advanced” forces would close with and destroy the remaining Allied naval forces in a warship surface action. This would then allow Japanese naval forces the freedom to neutralize Henderson Field through bombardment while covering the landing of the Japanese army troops to retake Guadalcanal and Tulagi.

Both Allied and Japanese naval forces continued to converge on 22 August and both sides conducted intense aircraft scouting efforts, however neither side spotted its adversary. But the disappearance of at least one of their scouting aircraft (shot down by aircraft from Enterprise before it could send a radio report), caused the Japanese to strongly suspect that U.S. carriers were in the immediate area. The U.S., however, was unaware of the disposition and strength of approaching Japanese surface warship forces. The Japanese had finally changed communications codes and the radio intelligence so important at Coral Sea and Midway was not helping VADM Fletcher.

Neither side had a firm idea where the other’s carriers were. Fletcher and his flattops were steaming about 250 miles southeast of Guadalcanal, staying beyond range of enemy air attack, where they could refuel when necessary and send air search patrols over the Slot to supplement the work of the longer-range PBYs and B-17s. Scout pilots flying from Henderson Field faced maddening technical difficulties. One day their radio communications were in perfect tune two hundred miles out from base; the next day they were utterly garbled or silent within twenty miles.

Effectively, two parallel but separate naval campaigns were developing. The seas immediately around Guadalcanal would be the setting for a campaign of surface fights between light forces for control of the seas. Farther out to sea, generally to the north and east of the Solomons, a less geographically constrained campaign would be fought as the roaming aircraft carrier forces made themselves selectively available to duel, striking with their planes but never coming within sight of each other.

At 09:50 on 23 August, a U.S. PBY Catalina flying boat initially sighted Tanaka’s convoy. However, Tanaka, knowing that an attack would be forthcoming following the PBY sighting, reversed course and eluded the strike aircraft. After Tanaka reported to his superiors his loss of time by turning north to avoid the expected Allied airstrike, the landings of his troops on Guadalcanal was pushed back to 25 August.

By late afternoon, with no further sightings of Japanese ships, and not knowing that Tanaka’s convoy had turned north, Fletcher launched a Saratoga strike group and a strike force from Henderson Field’s Cactus Air Force.

The strike should have reached the target around 1630. Nothing was forthcoming from other commands, notably McCain’s Airsopac.

As Fletcher waited for strike results, he pondered the latest hot intelligence from Pearl – the Cincpac daily bulletin unequivocally placed the Shokaku and Zuikaku “enroute Japan to Truk,” while a heavy cruiser and “possibly” two fast battleships were in the Truk “area” or “vicinity.” Thus Cincpac amended his earlier announcement that morning of two Shokaku-class carriers “in or near Truk.” The term “in or near” is not the same as “enroute to,” although Nimitz seemed not to have noticed the difference. Even so, Fletcher now had good reason to believe the nearest carriers were still north of Truk, itself more than eleven hundred miles distant from his present position. In fact, Nagumo cruised only three hundred miles northwest of TF-61, and Kond?’s Advance Force drew even closer. The reason for this was the colossal failure by the same radio intelligence network that forecast the Coral Sea and Midway battles. Its immediate effect was to delude Fletcher into believing it was safe to detach his task forces one at a time to fuel.

By 18:23 on 23 August, with no Japanese carriers sighted and no new intelligence reporting of their presence in the area, Fletcher detached Wasp (which was getting low on fuel) and the rest of TF 18 for the two-day trip south toward Efate Island to refuel. Thus, Wasp and her escorting warships missed the upcoming battle.

Initial Carrier action on 24 August

At 01:45 on 24 August 1942, Nagumo ordered Rear Admiral Chuichi Hara(with the light carrier Ryujo, the heavy cruiser Tone and destroyers Amatsukaze and Tokitsukaze) to proceed ahead of the main Japanese force and send an aircraft attack force against Henderson Field at daybreak.

At 09:35, a Catalina made the first sighting of the Ryujo force. Later that morning, there were several more sightings of Ryujo and ships of Kondo’s and Mikawa’s forces by carrier and other U.S. reconnaissance aircraft. Throughout the morning and early afternoon, U.S. aircraft also sighted several Japanese scout aircraft and submarines, leading Fletcher to believe that the Japanese knew where his carriers were – which actually was not yet the case.

Fletcher hesitated to order a strike against the Ryujo group until he was sure there were no other Japanese carriers in the area. Finally, with no firm word on the presence or location of other Japanese carriers, at 13:40 Fletcher launched a strike of 38 aircraft from Saratoga to attack Ryujo. However, he kept aircraft in reserve from both U.S. carriers potentially ready should any Japanese fleet carriers be sighted

Meanwhile, at 12:20, Ryujo launched six Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” bombers and 15 A6M3 Zero fighters to attack Henderson Field in conjunction with an attack by 24 Mitsubishi G4M2 “Betty” bombers and 14 Zeros from Rabaul. However, unknown to the Ryujo aircraft, the Rabaul aircraft had encountered severe weather and returned to their base earlier at 11:30. The Ryujo aircraft were detected on radar by Saratoga as they flew toward Guadalcanal, further fixing the location of their ship for the impending U.S. attack. The Ryujo aircraft arrived over Henderson Field at 14:23, and tangled with Henderson’s Cactus Air Force while bombing the airfield. In the resulting engagement, three “Kates”, three Zeros, and three U.S. fighters were shot down, with no significant damage done to Henderson Field.

Almost simultaneously, at 14:25 a Japanese scout aircraft from the cruiser Chikuma sighted the U.S. carriers. Although the aircraft was shot down, its report was transmitted in time, and Nagumo immediately ordered his strike force launched from Shokaku and Zuikaku. The first wave of aircraft (27 Aichi D3A2 “Val” dive bombers and 15 Zeros) was off by 14:50 and on its way toward Enterprise and Saratoga.

Japanese Aichi D3A1 Navy Type 99 Carrier bomber (Val), taking off from the aircraft carrier Shokaku.

After a morning of fruitless searching, about this same time, two U.S. scout aircraft finally sighted the main Japanese force. However, due to recurring communication problems, these sighting reports never reached Fletcher. Before leaving the area, the two U.S. scout aircraft attacked Shokaku, causing negligible damage, but forcing five of the first wave Zeros to give chase, thus aborting their mission.

About 1600, the Saratoga strike force (having returned from Henderson after the fruitless strike on the afternoon of the 23rd) arrived and then also attacked Ryujo, hitting and heavily damaging her with three to five bombs and perhaps one torpedo, and killing 120 of her crew. Also during this time, several U.S. B-17 heavy bombers attacked the crippled carrier but caused no additional damage. The crew abandoned the heavily damaged Japanese carrier at nightfall and she sank soon after.

At 1602 with a another TF-61 strike still under deliberation, both carrier radars registered a large group of bogeys one hundred miles northwest. The first strike of thirty-seven planes was coming straight in. At that same moment, 225 miles NNW of TF-61, the Shokaku and Zuikaku dispatched Takahashi’s nearly identical second wave of 27 Vals and nine Zeros. Abe’s vanguard force surged ahead planning to finish off the U.S. carrier force in night surface combat.

Time indeed expired for Fletcher, for TF-61 was about to suffer the feared air attack from an unlocated force.

Next: Part 13-2 “In coming”