Blown Slick Series #13 Part 4

“Scratch One Flattop!”

The Battle of the Coral Sea, fought from 4 to 8 May 1942 is historically significant as the first action in which aircraft carriers engaged each other, as well as the first in which neither side’s ships sighted or fired directly upon the other. And of great importance, the battle marked the first time since the start of the war that a major Japanese advance had been checked by the Allies.

The Port Moresby Attack Plan, Operation ‘MO’

In an attempt to strengthen their defensive position in the South Pacific, plus provide the air support bases to threaten Australia, the Japanese decided to invade and occupy Port Moresby (in New Guinea) and Tulagi (in the southeastern Solomon Islands). Admiral Yamamoto reluctantly agreed to the plan but was concerned with the potential impact on his effort to lure U.S. Navy carriers into an engagement at Midway. In typically complex fashion, in early May, they deployed five naval forces, including a covering group with the light carrier Shoho and five escorts, and Vice Admiral Takeo Takagi’s striking arm: Carrier Division Five (CARDIV 5) with heavyweights Shokaku and Zuikaku screened by eight escorts. Combined Japanese air strength of the three carriers was 141.

Nimitz was knowledgeable of the Japanese plan because of the ongoing breaking of Japanese communication code. He could only commit the carriers Lexington and Yorktown (Task Force 11 (Lexington) and Task Force 17 (Yorktown) under overall command of Rear Admiral Frank “Jack” Fletcher) because Enterprise and Hornet were already committed to the Doolittle Raid and Saratoga was still in repair after being torpedoed by a submarine in January.

Initially, the Japanese sent a small force to capture Tulagi and Gavutu Islands to establish a seaplane reconnaissance base across the sound from Guadalcanal (a name which meant little to anyone at the time), and on 3–4 May, successfully invaded and occupied Tulagi.

The Americans waiting for the Japanese invasion force to commence operations against Port Moresby, decided to strike Tulagi before turning to face the carrier threat. Communications concerns prevented Yorktown’s Task Force Seventeen from coordinating with Lexington’s Task Force Eleven, but nevertheless, Fletcher proceeded to launch strikes against Tulagi on May 4. In three waves Yorktown’s air group swarmed the anchorage.

Yorktown attackers at Tulagi

The Japanese carriers operating in radio silence north of the Solomon Islands, were engaged in refueling and could not react fast enough to launch a counter-strike on Yorktown; they were, however now alerted to the presence of at least one U.S. carrier and aware of the presence of U.S. carriers in the area, the Japanese fleet carriers pushed towards the Coral Sea with the intention of locating and destroying Fletcher’s carrier forces.

The result of a significant expenditure of ordnance by Yorktown’s airwing was that one Japanese destroyer was damaged and later beached, three small minesweepers and four landing barges sunk, and probably most importantly, all five H6K4 Type 97 “Mavis” flying boats present were destroyed, which adversely affected Japanese future search capability. The U.S. cost was three aircraft with all four fliers rescued.

Of note was the continuation of a trend observed in earlier raids by both forces’ aviators of misinterpreting or overestimating the size, type, and number of opponents ships, as well as the number damaged and sunk, in this case claiming several cruisers sunk (no cruisers were present) and several destroyers (one was present). Situational awareness on both sides would continue to be a problem throughout the following days.

But at least for the moment, the Japanese were forced off-balance.

On the 5th and 6th of May, both carrier forces tried to locate each other without success. Expecting the Japanese carriers to be supporting the invasion force that would have to round the eastern tip of New Guinea, U.S. carrier aircraft concentrated searches to the northwest, to no avail, and unbeknownst, the Japanese carriers had rounded the eastern side of the Solomon Islands and entered the Coral Sea from the east. Japanese tactical communications security here was superb. However, Japanese commander Rear Admiral Takagi, believing he was in position to surprise and trap the Americans, opted not to use his own carrier aircraft initially for search so as not to give away his presence and decided to rely on long range land-based and flying boat reconnaissance, but much of which had been significantly depleted at Tulagi. Fletcher was not helped by inaccurate reports from General MacArthur’s aircraft flying out of Australia that reported multiple carriers in company with the invasion force (and a lot else that wasn’t there). Also, probably confusing matters was the brand-new Japanese small carrier Shoho (18 operational aircraft) being in the vicinity of the invasion force, The result was that both commanders had lost situational awareness by 7 May.

On May 6 Rear Admiral Fletcher merged Task Force Seventeen with Fitch’s unit and Task Force Forty-Four, a surface force of U.S. and Australian warships. His combined strength was two carriers, eight cruisers, and thirteen destroyers, plus two vital fleet oilers. In addition to some 130 carrier planes, he benefited from long-range patrol bombers in Australia.

7 May -The clash of the carriers begins

Beginning on the 7th and continuing over two days the carrier forces engaged in the historic first carrier vs. carrier airstrikes .

Early on the morning of 7 May Fletcher detached TG-17.3, with the mission to move toward New Guinea and block the Japanese invasion force, which was covered by four heavy cruisers and other escorting cruisers and destroyers. The heavy cruisers and nine destroyers remained with TF 17. This action removed about a third of TF-17’s escorts and a third of its AAA defenses. Without air cover, TG-17.3 was potentially vulnerable to the 40 or so Japanese land-based bombers operating out of Rabaul.

[Interestingly it is believed that Fletcher based his decision on pre-war exercise experience, during which opposing carrier forces usually neutralized each other very early in the “battle” leaving surface ships to accomplish the mission, in this case, preventing the invasion of Port Moresby.]

In fact, the force was attacked later in the afternoon by two waves of about 30 land-based twin-engine “Nell” bombers. The first wave attempted a torpedo attack; five were shot down and no torpedoes hit. The second wave contented itself with a high altitude level bombing attack, with the usual results for that kind of attack, nothing. Displaying even worse ship recognition skills than U.S. pilots, the Japanese claimed to have sunk a California-class battleship, an Augusta-class cruiser, and damaged a Warspite (British)-class battleship, none of which were even remotely present. They were then attacked by three U.S. Army Air Force B-26 bombers from Australia; fortunately their bombing proficiency was even worse than the Japanese

Neither the carrier force knew where the other was, and both were searching in the wrong directions (in effect, both forces had gotten “behind” the other). Giving upon reliance of the land-based reconnaissance, the Japanese launched its carrier aircraft for search. At the same time U.S. carrier forces lofted their scout planes.

One Shokaku searcher nearly two hundred miles south of Takagi’s position misidentified the oiler USS Neosho and the USS Sims (DD-402), both operating well behind the U.S. carriers as a carrier and her escort. Shokaku and Zuikaku immediately launched seventy-eight planes (18 fighters, 24 torpedo bombers, and 36 dive bombers) – a full strike from both carriers.

[Not standard Japanese doctrine of launching half from each carrier, with the second half from each carrier for reserve/contingency.]

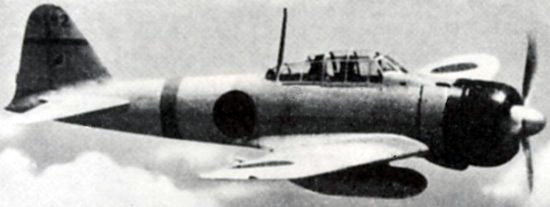

A6M ‘Zero’

At that point the situation became clouded in the inevitable fog of war. As the strike rolled in on the luckless Neosho and Sims, the Japanese strike commander did recognize the error and diverted his torpedo bombers onto a further search which proved fruitless . Four Val dive bombers hit Sims with three bombs, which sank quickly with high loss of life; the rest pummeled Neosho with seven hits and 15 near misses. Neither ship was able to radio a distress signal, so Fletcher remained clueless to the real location of the Japanese carriers.

Continuing the ongoing mis-identification problems which plagued both forces, an SBD on a scout mission from Yorktown erroneously reported two carriers operating in the vicinity of the Japanese invasion force. Based on that incorrect report, the U.S. launched a full strike from each carrier (93 aircraft total…50 from Lexington and 43 from Yorktown.) Fletcher learned of the error after the launch, and opted not to attempt a recall (something that hadn’t really been done before anyway) figuring that there were enough ships in the vicinity of the Japanese invasion force that there had to be something worth sinking, and still expecting to find the Japanese carriers there anyway. About that time, B-17s did find the invasion force including the small carrier Shoho. Fletcher radioed his strike leaders to proceed to the position plotted by the Army aircrews and at about 1040, Lexington’s air group found and attacked the Shoho.

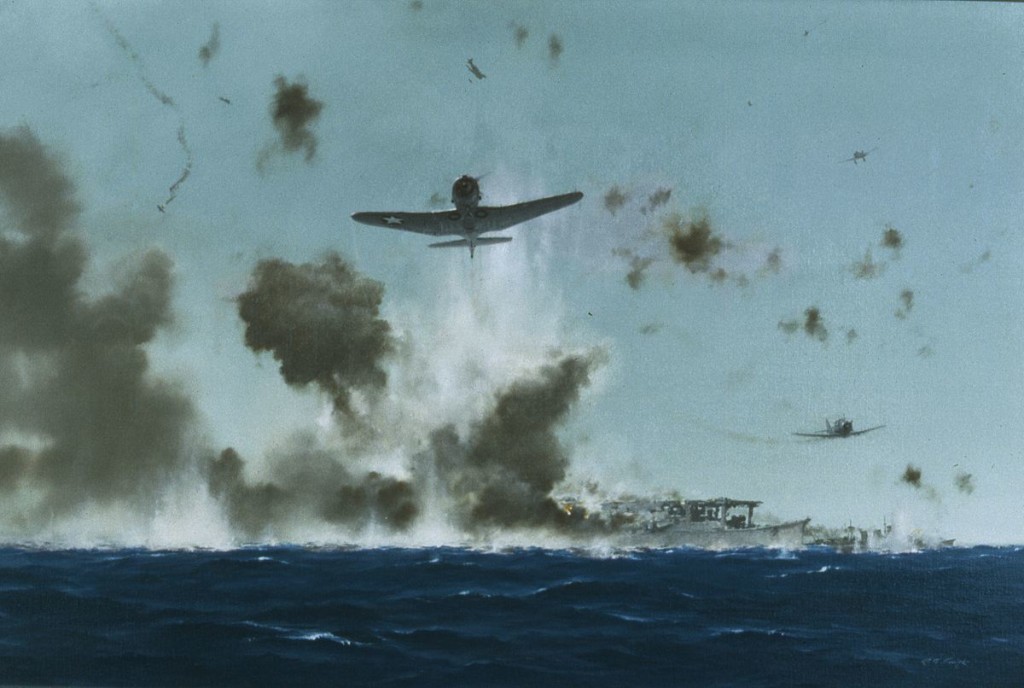

Fifty Lexington aircraft executed a coordinated attack as Shoho was attempting to launch a strike with her limited assets against TF-17. In the preferred sequence (as contrasted with operations at Midway) the dive bombers rolled in just ahead of the torpedo planes so that the dive bombers would draw fighters away from the more vulnerable torpedo planes and the bombs would disrupt Japanese AAA. Shoho’s combat air patrol (one Zero and two older A5M “Claude” fighters) gamely tried to disrupt the attack, succeeding in shooting down only one SDB after bomb release. Nevertheless, despite her limited defensive capability, Shoho managed to dodge the first 13 bombs dropped. Two bombs then hit and ignited massive fires. Lexington’s torpedo planes then executed a near perfect “anvil” attack (from port and starboard bow, so that no matter which way the target turns, a beam aspect is presented to one of the attacking sections). Five torpedo hits were fatal. At about 1125, Yorktown’s air group arrived and pounded the already burning stem-to-stern, listing, dead-in-the-water, and sinking Shoho with another 19 or so bombs, and somewhere between two and ten more torpedoes. Not surprisingly, Shoho sank quickly with heavy loss of (only 203 of 834 crew survived). Reportedly Lieutenant Commander Robert Dixon, heading Lexington’s scouts, radioed, the famous “Scratch one flattop!”

“Scratch One Flattop” by R.G. Smith

Given the number of U.S. carrier aircraft that attacked the Shoho, Rear Admiral Takagi was able to deduce that two U.S. carriers were involved as well as their approximate location. But identification and communications complications arose again as Japanese searchers confused and reported a surface ship task force as the U.S. carriers. In a gamble, Takagi ordered a dusk attack on the American carriers, knowing that it would require night recovery in deteriorating weather, something that neither navy rarely did on purpose. The mission consisted of volunteers from among the very best Japanese pilots in 15 torpedo bombers and 12 dive bombers from Shokaku and Zuikaku. The strike overflew the U.S. carriers, hidden below the clouds, and American radar proved a huge advantage, plotting the inbound raiders, launching a combat air patrol (CAP) which pounced on the searching Japanese with lethal results. Nine bombers went down, as did three U.S. Wildcat fighters. This loss of the torpedo bombers would prove critical the next day.

The remainder of the Japanese flight in returning, arrived over the U.S. carriers in darkness, mistook them for their own carriers, and attempted to recover on the Yorktown. One was shot down on approach and the remaining Japanese bombers escaped and then navigated 120 miles to their own decks and recovered. At the end of a long, confusing day, the U.S. and Japanese carriers were now only about 40–60 miles apart. The Japanese invasion force, deprived of air cover, reversed helm to await events.

At sunset on May 7, 1942, for the first time in millennia of naval combat, a fleet engagement had been fought beyond range of sailors’ vision.

8 May – The continuing battle creates consequences

The 8th of May, played out just like numerous pre-war fleet exercises in both navies. Both sides’ airborne scouts found each other about the same time, both sides attacked each other about the same time, and both sides effectively neutralized each other’s carriers about the same time. Unlike the pre-war exercises, however, there was no Battle Fleet to clean up afterwards (neither side had any battleships ).

TF17, Lexington and Yorktown, with 117 operational aircraft (31 fighters, 65 dive bombers, and 21 torpedo bombers) began the face off against the Shokaku and Zuikaku, with 96 operational aircraft (38 fighters, 33 dive bombers, and 25 torpedo bombers). Although the U.S. had numerical superiority, the weather favored the Japanese, as a front moved over the Japanese carriers hiding them under clouds, while the U.S. carriers were under mostly clear skies.

As before, American carriers and Japanese carrier and land-based aircraft began the day by seeking out the other. Within minutes of 8:20 both sides learned the other’s location, nearly 250 statute miles apart. Though the Japanese planes outranged the Americans’, both forces turned to engage. It was a close race as both sides launched within ten minutes of each other.

Japanese bomber prepare to launch

The U.S. launched first at 0900, with 39 Yorktown aircraft (six fighters, 24 dive bombers and nine torpedo bombers). At 0907, Lexington began launching 36 aircraft (nine fighters, 15 dive bombers, and 12 torpedo bombers). The two air-groups proceeded independently to the target. Shortly after, at 0930 Shokaku and Zuikaku launched a 69-plane strike (18 fighters, 33 dive bombers, and 18 torpedo bombers) in a single integrated strike package. At 1100, Yorktown dive bombers commenced their attack on the Shokaku. Zuikaku ducked under clouds and was not seen by any attacking aircraft. Lexington’s aircraft arrived at the target about 30 minutes later. At about 1115, the Japanese strike commenced its attack on both Yorktown and Lexington simultaneously.

All seven VS-5 (Yorktown) SBD Dauntless dive bombers attacking the Shokaku; harassed by Japanese fighters missed due to fogged windscreens and bombsights. At 1103, 17 VB-5 SBD’s attacked the Shokaku with multiple misses again due to the fogging problem, but one bomb hit almost at the bow and started a fire. A second bomb, dropped by Lieutenant John Powers, at the cost of his own and his gunner’s lives, hit near the island and started severe fires on the flight deck and in the hanger deck. With this hit Shokaku was rendered unable to operate aircraft for the remainder of the battle. As VB-5 concluded its attack, the nine TBD torpedo bombers of VT-5 commenced their attack. Fighter escort kept the Zeros off the TBD’s, but Shokaku, despite burning furiously, was able to avoid or outrun all the torpedoes.

At 1130 part of Lexington’s air group arrived over the Shokaku, four of Lexington’s command group dive bombers scored one hit on Shokaku. Eleven Lexington (VT-2) torpedo planes attacked Shokaku but no torpedoes hit. Two Lexington Wildcats were shot down while successfully protecting the torpedo bombers from Japanese fighters. The final tally: Shokaku was hit by three bombs, and unable to operate aircraft but still able to make 30 Kts on her own. The cost to the U.S. was two SBD Dauntless and three Wildcats. An additional Wildcat and two SBD’s (including the Lexington air group commander, Commander William Ault) disappeared returning to the carrier.

Even before the last American planes departed the area, their own ships were dodging bombs and torpedoes. Fully expecting to be attacked, TF-17 had launched a heavy CAP of 8 Wildcats and 18 SBDs (in an anti-torpedo plane role). At 11:00 Lex’s radar “painted” hostile aircraft inbound from the north, distance seventy-five miles— good performance for the equipment giving the defenders twenty-five minutes to react – and launched nine more Wildcats and five more SBDs. It did little good, despite radar fighter direction.

The Japanese targeted both carriers, about a mile and a half apart. As the U.S. fighters approached, the Japanese torpedo bombers escaped into the clouds, and the dive bombers were not intercepted until they began commencing dives. Yorktown evaded the torpedoes aimed at her, but Lexington, bigger and less agile, took two torpedo hits. Shipboard gunners downed four attackers before additional damage could be inflicted.

However, with only three of 18 Kate torpedo bombers shot down, nine attacked the Lexington and four went after the Yorktown (this is where the loss of torpedo bombers the previous night would prove crucial). The four that attacked the Yorktown all missed and two were shot down. The nine other torpedo bombers executed a doctrinal anvil attack on Lexington, which avoided the first five torpedoes but could not avoid the four coming from a different direction; two went under without exploding and two hit. The first torpedo hit was fatal, although it would take several hours before that would become apparent – among the overall damage, the port aviation fuel tank was cracked, and volatile gasoline vapors began to seep throughout the ship.

Nineteen Val dive bombers then attacked Lexington and 14 attacked Yorktown. Zeros successfully defended their dive bombers, so all 33 dropped on target. Two bombs hit Lexington, which caused minimal damage. One bomb hit Yorktown, which penetrated deep in the ship, causing significant damage, but Yorktown was quickly able to resume flight operations this damage was repaired* in time for Yorktown to participate in the battle at Midway; of note, had she been hit by a torpedo, that probably would not have been the case.

Japanese Torpedo Bomber attack amidst significant AAA

The Japanese lost five dive bombers and eight torpedo planes in the attack on the Lexington and Yorktown; however, battle damage was extensive to the survivors forcing seven more to ditch on the way back to the Zuikaku, and another 12 had to be pushed over the side due to severe damage as Zuikaku struggled to take aboard the remains of both Zuikaku and Shokaku’s air groups. Yorktown fighters, returning from the strike on Shokaku, shot down two more Japanese aircraft returning from the strike on the U.S. carriers; one was the Shokaku’s air group commander. The U.S. lost three Wildcats and five SBD’s defending the carriers.

Initially, it appeared that the U.S. carriers had gotten off surprisingly light from the Japanese air attack. However, at 1247, the gasoline vapors seeping through Lexington were ignited when they reached motor generators, resulting in a massive explosion. The fires quickly got out of control as numerous lesser and two more major explosions devastated the ship throughout the afternoon. At 1707 Captain Frederick “Ted” Sherman gave the order to abandon ship, and in what was arguably the most orderly and successful abandon ship in the history of the U.S. Navy, all personnel who were not killed in the air attack or the subsequent explosions were safely rescued.

The USS Lexington burning

At the end of the day, Yorktown had only 12 SBD dive bombers and eight TBD torpedo bombers still operational, and only seven torpedoes left. The battle of the Coral Sea cost the U.S. Navy 611 men from ships companies and thirty-five aircrew including 81 aircraft (35 went down with the Lexington) and 543 dead aboard Lexington, Neosho and Sims.

The situation was even worse on the Zuikaku; of 46 aircraft recovered on board, only nine were operational. Since 6 May, the Japanese had lost about 69 aircraft from Shokaku and Zuikaku, along with Shoho’s entire complement of 18 aircraft. Over 1,000 Japanese had been killed, most on Shoho.

Both Fletcher and Takagi decided that the best course of action was to clear out as fast as possible. Takagi was blasted by Yamamoto for his decision and returned to the battle area (by then most of his embarked aircraft were repaired and operational) in a vain search. Nimitz had not second-guessed Fletcher, and TF17 was long gone.

Some key points

- The Battle of the Coral Sea underscored that carrier warfare imposed a high price. Each side lost a flattop. The U.S. Navy lost sixty-seven planes, and Japan lost at least sixty-nine as well as some patrol planes.

- Thus, the first carrier battle indicated that either side could expect to lose about half its embarked aircraft to combat, accidents, and wastage.

- Ships were simply “hard to hit!” Difficulty arose from multiple factors: outside visibility and humidity problems in the cockpit, AAA and fighter defense capabilities, and ship’s maneuverability, not to mention lack of targeting technology.

- Events continually highlighted the problems of gaining and keeping situational awareness in war-at-sea in the face of difficulty in accurately identifying ships and planes given basic fog of war, pilot experience, expanse of the battlespace, and weather obscurations.

Tactically the Japanese won, as Lexington was far more valuable than Shoho, but strategically the battle was a victory for the Allies on multiple levels:

- The battle marked the first time since the start of the war that a major Japanese advance had been checked by the Allies.

- The Japanese attempt to invade Port Moresby was “postponed,” never to be attempted again, at least by sea.

- Badly damaged, Shokaku was forced out of the area, en route to repair in Japan. Zuikaku sustained no material damage, but her air group had been depleted, effectively removing Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s CarDiv Five from any near term operation ensuring a rough parity in aircraft between the two adversaries at Midway and thus contributing significantly to the U.S. victory in that battle.

- Yorktown was repairable and was a key at the Battle of Midway. As will be seen at Midway U.S. Navy damage control design and operations was significantly better than that of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

- The ninety prewar aircrew who died at the Battle of the Coral Sea began a slow hemorrhaging for the Japanese that would never be staunched.

* Epilogue

As noted Yorktown’s being repairable and then engaged at the Battle of Midway while Yamamoto’s CARDIV FIVE carriers were not was undoubtedly a huge game changer. One bomb that penetrated several decks on Yorktown started fires that could have been devastating, and if not causing complete loss, certainly worsening the damage to the extent that she would not have been at Midway.

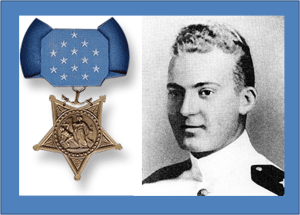

The Medal of Honor was awarded 464 times during WW II, 266 of them posthumously. Four were due to bravery at Coral Sea. Considering the above, the award of the Medal to Lt. Milton Ernest Rickets (USNA class of 1935), USS Yorktown officer-in-charge of the Engineering Repair Party deserves considerable reflection.

The Citation:

For extraordinary and distinguished gallantry above and beyond the call of duty as officer-in-charge of the Engineering Repair Party of the U.S.S. Yorktown in action against enemy Japanese forces in the Battle of the Coral Sea on 8 May 1942. During the severe bombing of the Yorktown by enemy Japanese forces, an aerial bomb passed through and exploded directly beneath the compartment in which Lt. Ricketts’ battle station was located, killing, wounding, or stunning all of his men and mortally wounding him. Despite his ebbing strength, Lt. Ricketts promptly opened the valve of a near-by fireplug, partially led out the firehose, and directed a heavy stream of water into the fire before dropping dead beside the hose. His courageous action, which undoubtedly prevented the rapid spread of fire to serious proportions, and his unflinching devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.

And now on to the Battle of Midway. See Part 5