I attended the Celebration of Life for Dave Snako Kelly on Saturday 3 May on-board USS Midway.Hot afternoon but not nearly as hot and humid as it was 42 years ago in the Gulf of Tonkin. Dave and all the rest of us were about to learn about real air war over North Vietnam. We were about to become “these good men.”

Dave and all the rest of us were about to learn about real air war over North Vietnam. We were about to become “these good men.”

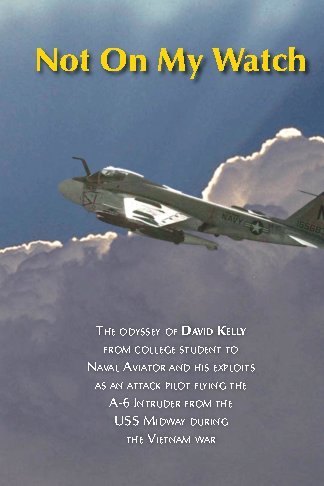

Dave was a great friend, superb Naval Aviator, member of VA-115 flying the A-6 Intruder off of Midway on the ’72 war cruise. He is also the author of the recently published story of his flying years Not On MY Watch.

For anyone who has followed Remembered Sky, you are aware that several chapters of his book have been posted here beginning with the Prologue. Snako was co-“owner” for Remembered Sky. Below is the Epilogue to Not on My Watch.

Epilogue

I started thinking about writing this memoir about 15 years ago, and I was amazed at how well I remembered some of the events that had taken place. I guess life-threatening events get burned pretty deeply into your brain.

I also found the writing to be therapeutic. It had taken me about 35 years and a trip to North Vietnam to get over being pissed-off about the War. It was an ugly mess of political failure and misplaced ideals. However, many of the participants were very sincere for their support of their flag, their country, and above all their fellow soldiers/sailors/fliers.

I walked away from the Vietnam War pretty confused and angry by the experience. After the first few burials at sea, I became numb. I’m sure that ‘survivors guilt’ coupled with, “Why him and not me?”, contributed to this feeling.

The aviators who were lost were my contemporaries and equals. For some reason their luck had run out, and the same thing could be my fate on my next flight. But you took that next flight, pushed any anxiety out of your mind, and did your best to fly your mission and return to the ship.

The emotions I felt after doing this for eleven months were too complex and difficult for me to deal with, and I knew that my life was going to change dramatically. Dianne was pregnant; and I had long since decided to leave the Navy. I needed to finda job, and we planned to move back to Southern California.

There just wasn’t time for me to try and sort out my emotions,so I packed them up and buried them with many of my memories from those chapters of my life. This approach worked and with time, I was able to put some of the more disturbing parts of that period behind me. It didn’t, however, eliminate the underlying issues.

For years following the war I had been fighting a personal problem of conscience. Whenever I spent any time thinking about it, I felt terribly guilty for probably killing innocent civilians. (When bombs fall from planes, there is always a possibility of them doing that.)

I tried to justify my actions logically based on arguments like: 1) I was carrying out the wishes of my government, 2) people were trying to kill me and I was just defending myself, and 3) my actions had helped ‘liberate’ the POW’s and bring an end to the war. This, however, doesn’t really address the issue of whether it was ‘right’ to have done this. And there were quotes from people like Albert Einstein who said, “It is my conviction that killing under the cloak of war is nothing but an act of murder.”

There was no way I could resolve these philosophical arguments, I just shoved them into the background. It wasn’t difficult to keep them buried during the period that I was trying to keep food on the table, earning a PhD in engineering, being a Navy Reservist, and helping to raise our three boys.

They say,’ time heals all,’ but that didn’t happen for me. I think the healing process requires you to accept historical reality, let your memories fade, and somehow come to grips with your transgressions. I was working in aerospace and contributing to warfare in general. As time went by I became acutely aware that for most of my adult life I had either dropped bombs or had made ‘bombs’ (weapons).

In 1997 I left Hughes Aircraft Company and moved to Hughes Space and Communications doing satellite communications. I was finally out of the ‘bomb business.’

In 2004 remnants of Mike and Al were returned to Arlington National Cemetery for burial. A few members of the squadron were initially notified of their internment, and that was enough to light the spark. Several hundred phone calls and emails later a majority of the squadron converge on Washington to attend the ceremony.

People who had not seen each other for thirty years, but who had shared the same traumatic experiences, were able to almost pick up from when they had last seen each other. Despite the underlying grief, this first reunion of the squadron reminded all of us of how lucky we were, and how much wehad counted on each other. These special relationships had been forged in fire, when we lived it on the ragged edge. We had all been switches which could be ‘on’ or ‘off’ in an instant.

The reunion rekindled my desire to tell the story of ‘My Watch’ (Our Watch). Telling this story, however, made me once again face the fact that I had probably taken some civilian lives during my more than 200 combat missions.

Going into the Navy as opposed to being drafted hadn’t really been much of a choice in the ’65 to ’68 time frame. But I had ‘chosen’ to go into aviation, I had ‘chosen’ to fly jets, and when the time came to selecting an aircraft I had ‘chosen’ the A-6, a bomber. So I had really chosen to put myself in the position of a warrior who dropped bombs on people.

As a result of being so complicit in getting into that position, I felt that I was accountable for my actions. Unlike my Catholic squadron mates, who could seek absolution, my view of the world was that ‘a card laid’ is ‘a card played.’ Hence, I was forever responsible for my actions.

In 2008 Dianne and I visited North Vietnam for about a week. I had a lot of trepidation about the trip, but since we were using Dianne’s United Airlines (flight attendant) benefits, this wasn’t going to be a costly affair. I also knew that I would never pay to travel to that country.

We arrived in Hanoi and found a good hotel with a very gracious staff. We walked to the Hanoi Hilton, the prison where a number of the POW’s had been held. There were pictures of the POW’s, and there were pictures of the destruction which had been wrought on Hanoi during the December ‘72 bombing. I returned to my hotel feeling more guilty than ever and considered just bailing out and heading home.

The next day we took a bus to Ha Long Bay for a short cruise in the islands at the northern end of the Tonkin Gulf, an area with which I was very familiar. The bus trip took the main highway heading east out of the capital. It went through towns like Bac Gang and Hai Doung, then skirted Haiphong passing the Uong Bi Power Plant. These had all been targets I had struck these places at night in ’72. They were bustling with people. Had this been the way they were when we were bombing?

When we returned to Hanoi following the cruise, we took a guided tour of the city. Our guide was a 35-ish very entrepreneurial Vietnamese man who was dedicated to his family and his fledgling travel business.

After we had visited some of the noteworthy sites of the city and Ho Chi Minh’s tomb, our guide commented about the ‘War with America.’ I asked him when that had occurred. He said that was between 1973 and 1975. This astonished me, so I asked what the war prior to that had been. He responded that it had been the ‘Civil War between North and South Vietnam.’ That blew me away.

I realized two things at that point. If the ‘Yankee Air Pirates’ had not bombed the two industrial cities, Hanoi and Haiphong, then regardless of how they had gotten there, the POWs would never have been released. And secondly, when we thought the war was over, the North Vietnamese really considered it had just started.

After the trip to North Vietnam I decided I was not going to beat myself up over my involvement in Vietnam. Something far bigger than me had kept me alive, so I could raise a family. And all I can do is keep living my life in an honorable way, and see to the best of my ability that my children, grandchildren, and all that follow have my perspectives and personal misgivings about this period of history.

Writing these memoirs has helped tremendously in the healing process.

The End

David Martin Kelly, age 68, a longtime resident of Westlake Village, California, died peacefully at home on March 16, 2014, with his family at his side. He is survived by his wife of 44 years, Dianne Kelly, his three sons, Christopher, Peter and Bryan, their wives and eight grandchildren.

My friends… we have not just dreamed… we have done… all this and more.

A friend is gone, he will not be forgotten. Here’s a nickel in the grass.