When Carole Hickerson’s husband was missing in action during the Vietnam War, she started a movement of families frustrated by a lack of information on their missing loved ones.

RememberSky Note: Carole and Jim Hickerson are great friends. Jim was Vice Commander at Pacific Missile Test Center when I was in flight test and Bill Thomas and I did a 2-plane A-7 Corair II fly-over/departing man for his retirement ceremony. He returned the favor being the speaker at my retirement. Jim was one of the first test pilots for the A-7 and unfortunately was the pilot of the first A-7 shot down over North Viet Nam, spending over 5 years in the Hanoi Hilton. This series on Operation Homecoming began with telling the story of Jim and myself talking to high schoolers at Rio Mesa and the “story of the ropes.”

Carole was married to a Marine CH-46 pilot shot down in South Viet Nam on 3 June 1967. She became one of the early fighters in “the war of the wives” back in the states to spread the word on the treatment and lack of knowledge about the POWs. In this capacity she designed a letterhead for the POW-MIA organization. She’s quick to point out and asked me to emphasize that she had nothing to do with designing the flag itself. Below is a story I found by Steve Murray published in Midweek in July 2010 prior to an award for Jim and Carole. I am most appreciative to Steve for allowing me to publish on Remembered Sky. It is my way of telling their story and recognizing the “above and beyond” efforts of the National League of Families of American Prisoners of War and Missing in Action in Southeast Asia.

Lady and the Flag

By Steve Murray

There are some people history just won’t let us forget – many of them more infamous than famous. Then there are the countless others who go unnoticed or disappear into everyday life to be unfairly forgotten once the mission to which they have dedicated their lives has finished.

Carole Hickerson is one of the latter. She didn’t write the horrifying novel that helped end deadly working conditions in early 20th century U.S. factories. She didn’t write the song that brought to light the economic and social disparity between white and black America six decades later.

What she and a dedicated group of other young women did in the late 1960s and early ‘70s was equally as important. They changed the way the nation looks at its servicemembers and veterans. Hickerson, for her part, helped create one of the most-recognizable symbols of anger, despair, admiration and support.

Hickerson married her college sweetheart, Steve Hansen, in 1962. As a boy, Hansen dreamed of flight while watching planes take off from California’s Oxnard Air Force Base. Hansen realized his dream in 1964 after he enlisted in the Marines. Two years later he was sent to Vietnam, leaving behind a young wife and a son he had never met. During his year-plus tour of duty, the CH-46 helicopter pilot was shot down three times. Once he found refuge in a cave. The second time safety came in a rice paddy.

Hickerson married her college sweetheart, Steve Hansen, in 1962. As a boy, Hansen dreamed of flight while watching planes take off from California’s Oxnard Air Force Base. Hansen realized his dream in 1964 after he enlisted in the Marines. Two years later he was sent to Vietnam, leaving behind a young wife and a son he had never met. During his year-plus tour of duty, the CH-46 helicopter pilot was shot down three times. Once he found refuge in a cave. The second time safety came in a rice paddy.

But on June 3, 1967, his luck ran out. Hansen was shot down in Laos and taken prisoner. He wouldn’t return home until 1999 when his remains – a single tooth – were recovered and sent to the Central Identification Laboratory, Hawaii. In 2000 he was then finally given a proper burial at Arlington National Cemetery. By then, his widow had remarried, adopted two children and helped change a nation. The homecoming was both welcome and difficult.

“Although it was hard to go through, it means a lot to have Steve buried in the country he so dearly loved,” says Hickerson.

Still a head-turner at 71, and with humor and optimism that radiates from her sparkling eyes and dazzling smile, Hickerson remains much the same person as the one who took on U.S. policy, the Cold War, disinterested enemy leaders and a country at war with itself.

Like most family members who lost loved ones during the Vietnam war, Hickerson bore her burden in silence. U.S. policy was to keep information secret regarding soldiers and airmen missing in action.

Like most family members who lost loved ones during the Vietnam war, Hickerson bore her burden in silence. U.S. policy was to keep information secret regarding soldiers and airmen missing in action.

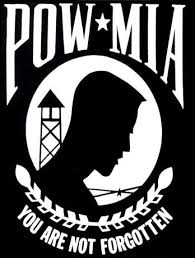

(Note: Steve’s profile became the center of the POW-MIA logo)

“That went on for so long. From ‘67 to the end of ‘68, that’s the policy I followed,” she says. “Very few people knew that Steve was listed as missing. It was going against government policy, especially when they said if you go public it could harm your husband, son or whoever.”

The U.S. was not acknowledging operations outside of Vietnam, and that made getting information about servicemembers lost beyond its borders nearly impossible. North Vietnam wouldn’t release a list of prisoners, and families didn’t know if their loved ones were alive or dead.

Eventually she grew tired of the silence and decided to speak up.

“I had a hard time even finding out where he went down,” she says. “It wasn’t until some of his squadron mates came back, and even then I remember one of them pulling out a big map and not even saying it out loud, not saying anything, just pointing to where he was shot down.”

Soon after she began a letter-writing campaign to every address she could find. She wrote to 350 newspapers asking readers to write their representatives and North Vietnamese communist leaders. She wrote to embassies and radio stations, religious groups and politicians. Some were helpful, others were not. Some returned checks she sent to pay for ads, running the ads for free. Others wrote back, saying her efforts were worthless since President Richard Nixon was doing everything he could for the missing or captured. Hickerson thought she was alone but quickly discovered there were thousands like her. She was flooded with letters from wives, mothers, sons and daughters. She joined with other women in California to help spread awareness.

A movement was born. Sybil Stockdale, wife of then-Cmdr. James Stockdale, who would become one of the most decorated servicemen in U.S. history and who famously beat himself in the face with a stool so his captors couldn’t use him for propaganda, came on board. Mrs. Stockdale enlisted a lawyer friend who helped the women establish the National League of Families of America’s Prisoners of War and Missing in Action in Southeast Asia. Using her Washington connections, Stockdale opened an office in the capital, donated by the American Legion.

Sponsored by a Catholic newspaper, she and three other wives went on an international tour trying to put pressure on North Vietnam. The Department of Defense advised them where to go. With pressure from families mounting, the suffer-in-silence policy was quietly repealed in 1970. They met with Pope Paul at the Vatican. They sat with Indira Gandhi. They flew to Laos trying to get to Hanoi, but weren’t allowed in. They went to England and France, Norway and Egypt, Italy and Germany and finally the Soviet Union, where they were apprehended and locked in an airport hotel until they were kicked out of the country.

Sponsored by a Catholic newspaper, she and three other wives went on an international tour trying to put pressure on North Vietnam. The Department of Defense advised them where to go. With pressure from families mounting, the suffer-in-silence policy was quietly repealed in 1970. They met with Pope Paul at the Vatican. They sat with Indira Gandhi. They flew to Laos trying to get to Hanoi, but weren’t allowed in. They went to England and France, Norway and Egypt, Italy and Germany and finally the Soviet Union, where they were apprehended and locked in an airport hotel until they were kicked out of the country.

Such adventure would have discouraged most activists. But these woman were motivated.

“I probably should have been (scared),” Hickerson says with a laugh. “I look back at it now and say, ‘Oh my gosh, what a dummy!’”

A second trip included stops at the Paris Peace Talks and at the North Vietnamese embassy in Laos, where they once again tried to get permission to fly to Hanoi. Once again they were denied and their request to forward mail was refused. Communist officials met with some of the wives, but not Hickerson. She was off limits; her husband had been shot down in Laos.

“You can’t imagine the cloak-and-dagger aspect of the whole thing. When they went in, and I got to sit on the side, the North Vietnamese representative met with the other three wives, and you could hear something going on behind a curtain. Everything was surreal.”

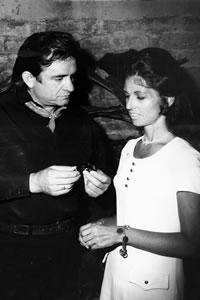

Back in the U.S., Hickerson recruited actors, musicians and politicians. California Gov. Ronald Reagan gave his support, as did Nixon’s staff. Peter Fonda spoke at rallies, Johnny Cash lent a hand and John Wayne wore Steve’s POW/MIA bracelet and sent gifts and letters to Hansen’s 8-year-old son Todd for years, often ending the notes: “Give ‘em hell.”

Ronald Reagan gave his support, as did Nixon’s staff. Peter Fonda spoke at rallies, Johnny Cash lent a hand and John Wayne wore Steve’s POW/MIA bracelet and sent gifts and letters to Hansen’s 8-year-old son Todd for years, often ending the notes: “Give ‘em hell.”

But Hickerson’s journey wasn’t always pleasant.

Invited to speak to numerous community organizations and at colleges across the land, she found the reception difficult at times.

“I’ve spoken at colleges and had things thrown at me by the students and was booed, ‘Your husband got what he deserved, ‘that sort of thing. All of us did the things that we did just because we cared so much. It was just something I had to do at the time.”

deserved, ‘that sort of thing. All of us did the things that we did just because we cared so much. It was just something I had to do at the time.”

Hickerson’s efforts put pressure on both the U.S. and North Vietnam. Living conditions for the captives improved. She still knew almost nothing about her husband’s fate, but her support never wavered.

“I wrote to Steve every night. The letters I sent off would come back and packages that we sent through leftist organizations were returned after they had taken out the stuff they wanted. I guess I was just stubborn.”

That feeling changed in 1973 at a White House reception for POWs. There she met Sgt. Frank Cius, a crewmember aboard her husband’s helicopter. Cius told her Steve was injured in the crash, that he was involved in a firefight with enemy soldiers and that he doubted her husband could have survived.

“He was the first one who had given me definitive information that Steven had not made it,” she says.

Even with some closure, the next several months were tough. Almost nightly on TV she saw POWs returning to their families. Each time she cried, hoping to see Steve walk off the plane. Slowly she worked her way through the pain with the help of family and friends. A few months later, what she likes to call the second chapter of her life began at a POW event in the Cotton Bowl.

Ross Perot and some other Dallas businessmen put on a welcome home party that featured, among many others, Bob Hope and Tony Orlando and Dawn, whose hit Tie a Yellow Ribbon had become a symbol for the movement. Carole was invited. Sitting next to her was former POW Jim Hickerson.

“This was an emotional time for me,” Carole recalls. “I was coming to the realization that Steve wasn’t coming home, and Jim is realizing that what he thought was in fact was no more. (Hickerson’s wife had remarried while he was a POW). Tears are running down my cheeks and Jim, who is a very soft-hearted soul, leaned over and just gave me a little kiss on my cheek.”

From that simple gesture of support a friendship slowly evolved.

“He asked if he could call me and it was just to commiserate with each other. I was living in El Toro and he was stationed at Lemore, Calif. I would listen to his tale of sadness and he would listen to mine.”

Jim’s playful nature and his kindness toward Todd eventually won her heart. They were married in Orange Park, Fla., in 1974 after Steve’s status was officially changed to Killed in Action.

“I am so very fortunate to have had two wonderful husbands,” she says.

Carole retired from her up-front activism after the wedding. She felt she had done what she needed to do and it was now time to devote herself to her new husband.

Jim retired from the Navy in 1984 and took a job with defense contractor Antion. In 2000 they relocated to Hawaii after the company asked Jim to head up its new island office.

Little Jim, the boy they adopted and saved from abortion just 12 hours before the surgery was to take place, and Jenny, whom they adopted as a 5-year-old after she was abandoned in a South Korean bus station, had graduated high school, making the move easier.

Now it’s time to relax. Sort of. Jim is retired but is active in the Navy League, the Pacific Aviation Museum and is on the board of The Armed Forces Communications and Electronics Association. Carole also is involved in the Navy League, is an elder at First Presbyterian Church and a member of Promote Education Opportunities, which provides scholarships for women. One day she wants to write a book about her and Jim’s experiences, to leave the story to their three children.

But Carole Hickerson’s legacy is guaranteed. Even if few realize that the second-most recognizable flag in the U.S. came from her unintended design.

In 1971, the League of Families had a name, a mission and thousands of supporters. But it didn’t have a logo. Using her background in art, she created a simple design: the silhouette of a man’s head, barbed wire, a guard tower and a simple message, You Are Not Forgotten. The silhouette is of Steve.

“I do not take credit for the flag,” she says, admitting she doesn’t know who create it or when it happened, but is pleased the logo has grown to symbolize all people in uniform and not just those who are captured or killed.

Still, those veterans who served and didn’t get recognized hold a special place in her heart: “I feel for the Vietnam veterans who came home and didn’t get the attention the POWs got, and Jim will say that. All of the men and women who served should have gotten accolades too, yet veterans came home and were spat upon.”

Hickerson downplays her role in today’s appreciation of our armed forces. But long ago she forced us to take an honest look at the men and women in uniform. She let us know that while it is acceptable to criticize U.S. policy, those tasked with carrying out that policy deserve respect and honor. That is her place in history.

******************************

Jim and Carole Hickerson will be were honored for their service to the Navy League at the American Patriot Awards Dinner Aug. 7 (2010) at Hilton Hawaiian Village.