Professional history of war mostly addresses major battles, the dates, the generals, the admirals, tactics and technology, and then analysis of results, all for obvious reasons. But significant detail is invariably lost particularly when one event leads to a most significant occurrence -the end to the conflict. Almost without exception, this thread – the ending of Linebacker II with the agreement by the North Vietnamese to return to the negotiations in Paris on 2 January 1973, leading to President Nixon’s announcement on the 23rd and formal end of the Vietnam war on 27 January, and finally the return of our POWs – constitutes the concluding remarks of the written histories of the war in Vietnam.

(Indeed the almost universal connection with the Christmas bombings and the war’s end is why I continue to provide posts under “Christmas Stories.”)

Yet, air operations in Southeast Asia continued until 15 August 1973. Twenty-eight more airmen would be killed and 26 aircraft lost, the last not until June. The previous post, “A Gentlemen’s Gentleman,” told the story of one loss, that of VA-56 pilot John Lindahl. Below Dave Kelly picks up his story from Not on My Watch as USS Midway departs Singapore after Christmas R&R on the way back to the Gulf of Tonkin with the story of another of those post-Linebacker II losses – the shoot-down of VA-115 aircrew Mike McCormick and Arlo Clark.

Continuing excerpts from Not on My Watch (Chapter 42) by Dave ‘Snako’ Kelly

In January of 1973 after an abbreviated port call in Singapore, Mondo and I bid farewell to our wives, and MIDWAY headed back to the Line…

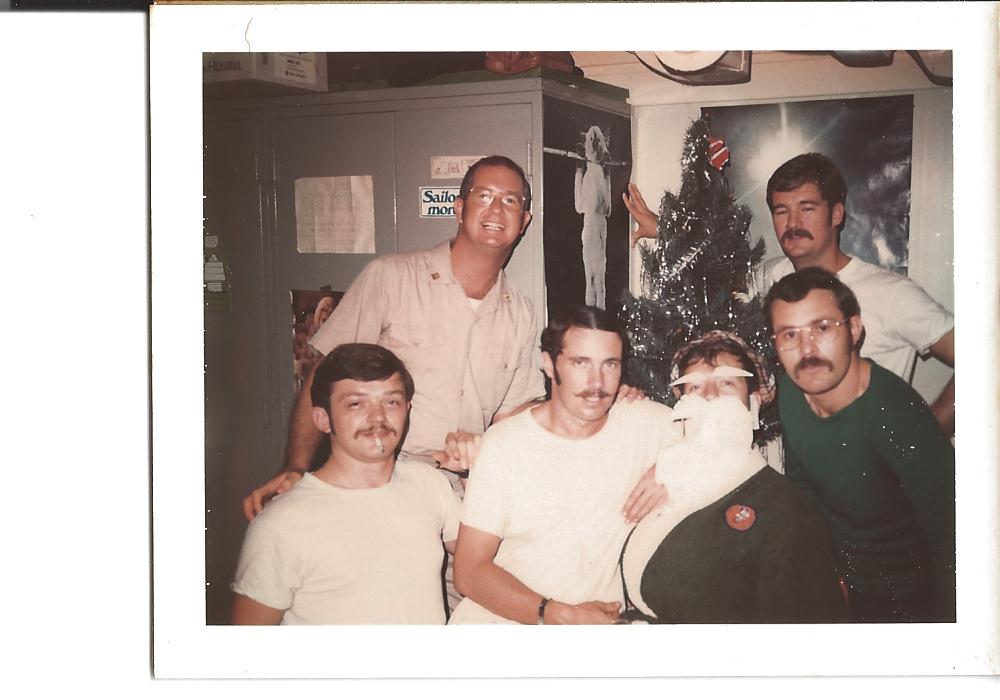

VA-115 parties with “Santa” on the way to Singapore. Mike McCormick is on Santa’s lap

We returned to the line via a short stop in Subic Bay. I think that visit was primarily for re-supply. During the December bombing we had expended a huge amount of ordnance, so I’m sure part of this visit was to re-stock the MIDWAY’s magazines. For me the visit to Cubi was an onboard affair. My failure to show up for the watch aboard ship in Singapore had caught up with me, and I was ‘invited’ to stand a few onboard watches for that in-port period.

During this visit to Cubi we also had to pick up new aircrews that were joining the squadrons of CAG5. The cruise was entering its 9th month of a planned 7-month cruise, and some of the pilots and crew members were scheduled to rotate to their next assignments. As we headed back to Yankee Station they reformulated several of the pilot-BN teams.

LT Koch and I had flown together for nine months. We had been everywhere in the country by that time; and we knew it rather intimately. Each of us attributed the other one for keeping us on the right side of the grass. Despite some protesting we knew that breaking us up was the right thing to do. Since the new guys would be seeing this type of combat for the first time, there needed to be some experience in each cockpit. Shylock was assigned to fly with a new pilot, so I went back into combat without an assigned BN.

We arrived back on the line on the 4th of January. The primary combat missions for the A-6s were night SAM suppression strikes. These missions were carried out just prior to B-52 bombing runs in the central part of North Vietnam, RPs II, III, and IV.

Unlike RP VI which is pretty wide and level, this area in the southern part of the country is the skinny part of North Vietnam extending south along the coast. The area by the coast is typically flat, but as you move inland the hills rise up to the Laotian Border. And north of Vinh these hills extend almost to the Tonkin Gulf.

These hills aren’t particularly high, maybe 1000 to 2000 feet, but they are scattered rather than being a ridgeline. You couldn’t treat this region the way you could the heartland of RP VI with its big wide flat plain, which at low altitude gave you a lot of lateral maneuverability.

At this point in this seemingly endless cruise, I considered this ‘SAM suppression’ a ridiculous mission. They didn’t know where the SAM sites were, because these were mobile SA-2s. These sites could be broken down and moved to a new location in a matter of hours. The bad guys knew what we were doing, so they wouldn’t leave these sites in the same place too long. So all we could do was to bomb a set of coordinates that were ‘suspected’ as a SAM location.

As a result it was doubtful that we did anything other than give the air defenses a bunch of targets to try and engage, and thereby give the BUFFs a little cover in the confusion. (I think this was probably a tactic sponsored by the same Air Force Senior Leadership who had their B-52s flying into Hanoi using WWII formation tactics.)

There was also nothing of high value in this area for the B-52s to strike. These missions were just marking time and keeping some semblance of pressure on the North Vietnamese. I think the strategy was that this pressure would motivate the Paris peace negotiations, which had been re-started following the December bombing. It may have been that our mission was just to allow the Navy to continue to ‘play a part’ in the war effort. (I had lost all semblance of idealistic goals at this point. All I wanted was to not be killed on the last day of the war and to get home safely.)

The weather in Vietnam had changed in the two weeks we were off the line. Instead of broken clouds at 1500-2000 feet, there was a solid overcast with the tops at about 4000 feet. Above the clouds it was perfectly clear, and below the clouds it was completely socked in solid down to 500 or 1000 feet above the deck. At night you had a brightly moon-light expanse of cloud tops which looked like whipped cream had been poured over the country. Occasionally this was punctuated by a hilltop sticking out of the soft, white cloud texture.

When we arrived at Yankee Station, I flew several daylight missions and tanker hops. On January 7th I flew a daylight mission with CJ Witkowski, and on the 8th CJ and I flew one of the night SAM suppression missions.

At the pre-flight briefing we talked over our strategy. We figured we had two choices, run our attacks at low altitude in the clouds in this medium threat area, or run the attack at 6000’, about 2000’ above the cloud tops. Running the attack lower would typically assure more accuracy hitting a target. But . . . we didn’t really have a well-defined target, just a set of coordinates. Furthermore, the standard procedure for operating in a SAM environment was to not get into instrument conditions (flying in clouds).

This was ‘sage’ advice based on the fact that it would be impossible to out-maneuver a radar guided SA-2 Guideline Missile traveling at ~2000 Mph, if you couldn’t see it. 2000’ above the overcast would supposedly give you enough time to make visual contact with the SAM, determine the geometry, and initiate an escape maneuver.

CJ had been flying with LCDR Craig, so he had seen his share of SAMs at night. We mutually decided that going high would be a far better plan. A few of the experienced crews in the squadron evidently decided to fly these missions low, the same way we had been flying at night in Haiphong.

CJ and I flew our first night SAM suppression mission successfully at 6000’ above the ground on January 9th. The target was somewhere north of Vinh, so we ran the target from the south to north paralleling the coast. This kept us in a low threat area for most of the attack.

I don’t think we saw/heard any activity on the ECM gear until we were very close to the release point. Once we dumped the ordnance we immediately headed east toward the water and chalked up another ‘mission completed’, i.e., the bombs had successfully hit the ground in North Vietnam near the coordinates we had been assigned.

For the midnight (first launch) on January 10th Mondo and Arlo the consummate professionals must have chosen to fly a SAM suppression mission at low altitude.

I was flying a tanker that night with LTJG Watson. We were part of the second launch and took off just before 2:00 AM. Our mission was to tank the BARCAP fighters.

We climbed to altitude, rendezvoused with the F-4s, and topped them off on their way to their BARCAP station. The ship was operating at South Yankee Station, so it wasn’t too far off the coast. The BARCAP station had now moved off of RP IV. Once we complete our primary mission we set up a race track pattern off the coast to conserve fuel for the end of the cycle. A little after 4:00 AM we would support the recovery.

We were flying along ‘fat, dumb, and happy’ at 20,000 feet conserving fuel and dealing with the boredom of a night tanker mission when we heard the ominous radio transmission on the Guard Channel, “A-rab Beeper, come-up voice.”

The ‘beeper’ being referred to was the device in the ejection seat of most military aircraft. This device is activated during an ejection or other crash which results in the separation of the ejection seat from the aircraft. The beeper indicates that an ejection seat had left an aircraft.

When a beeper was heard, the response required by any aircraft hearing the transmission is to make the request, “Beeper, beeper, come up voice.” There was always an attempt to establish communications with any crew members who had survived the crash. (These transmissions are made on the Guard Frequency, which is monitored by all aircraft and is used by the survival radios carried by crew members.)

The transmission we had heard, however, was more than a general request. By asking ‘A-rab Beeper’ someone had already determined that the plane associated with the beeper was an A-6 from VA-115.

In our cockpit this hit us like a hammer. In nine months of combat flying into the most heavily defended area of North Vietnam we had never heard a transmission like that. We had heard transmissions for “Raven Beeper”, “Champ Beeper”, “Switchbox Beeper”, and “Rock River Beeper”, the other combat squadrons in CAG5, but never an “A-rab Beeper”.

VA-115 had planes coming back shot up, but we had never lost an aircraft in combat. We lost three aircraft around the ship. Fast Eddie and LT Houser had ejected from a tanker which had caught on fire during the first line period. Curley had also stepped out of a tanker, and Claw had lost a wheel during a night landing with hung ordnance onboard his aircraft a few line periods later. The aircraft had careened up the flight deck and into the parked aircraft on the bow of the ship. Bix, his BN, had ejected unsuccessfully into the South China Sea. (Claw had stayed in the aircraft, and walked away from the crash unscratched.) LT Donnelly, Mondo’s BN, had been the only VA-115 crew member killed in combat.

“A-rab Beeper” meant that an A-6 had crashed, and this was most likely a combat loss. And the fact that the same transmission was being repeated meant that the aircraft making the call was not getting a response from the crew.

At that point we didn’t know which crew had been lost. All we knew was that there had been two VA-115 strike missions launched on the first go, and one of them had probably been bagged. We proceeded to go through what we knew relative to the flight schedule. Neither of us had been in Ready Room Five for the first launch, so we didn’t know who was flying. Through a process of elimination we narrowed it down to Mondo and Arlo or Skipper and Karcewski. We didn’t learn who it was until we landed on the ship on the second recovery.

We landed, debriefed the aircraft with maintenance, and dropped our flight gear off at the locker. As a tanker we were at the tail-end of the second recovery, so most of the enlisted crew members were unaware that the Squadron had lost a plane. When I entered the Ready Room, I heard the voice of the Skipper.

While it was devastating to lose anyone, I was overwhelmed, when I realized it was Mondo. As roommates Mondo and I had been ‘brothers in arms’. We had the same general philosophy of the war, and we respect each other’s flying abilities and head work. We had both ‘dodged bullets’ so many times; we just didn’t acknowledge the fact that we were still vulnerable.

The rest of the flights in the early morning hours kept transmitting the “A-rab Beeper” query. No responses were received. I had a strike flight in the late morning near the end of the day’s flight schedule. I requested to fly it with Shylock and LCDR Craig agreed.

There was still a solid overcast over North Vietnam, but it was daylight, so we punched through the clouds. This put us about 1000 feet above the ground under a 1500 foot overcast. As a pretty good-sized target against a white cloud background this was a somewhat precarious position for combat flying. The key was to keep your speed up and keep the aircraft jinking.

We flew in the general area where we thought Mondo and Arlo had gone down. In visual conditions you could avoid the hilltops, but in the low light conditions under the cloud deck all that was visible was a sea of green jungle. We didn’t see any AAA, but we were getting ‘pinged’ by some fire control radars. The SAMs left us alone.

We were able to loiter in the area for about a half hour. Several other A-6 crews flew in this same area during the last three daylight launches on the 10th. No one saw a sign of the downed A-rabs.

The loss of Mondo and Arlo hit our Squadron very hard and the whole CAG5 air wing mourned their loss. Mondo was one of the strongest JO pilots in the squadron, and he had seen a lot of combat ops. He was known and respect by both junior and senior officers throughout CAG5. Arlo was very junior, but he was recognized as a ‘tiger’ by the fighter and attack squadrons.

Mondo had more than his share of night SAM engagements. He and Arlo had been flying together for the last half of ’72 following Donnelley’s death, and they were considered by all to be a very solid crew. The sickest part of their loss was the ‘cheap’ target for which they had been wasted; a God damned set of coordinates in the coastal jungle of North Vietnam. It turned out that they would be the last A-6 crew lost in Vietnam.

Mondo had more than his share of night SAM engagements. He and Arlo had been flying together for the last half of ’72 following Donnelley’s death, and they were considered by all to be a very solid crew. The sickest part of their loss was the ‘cheap’ target for which they had been wasted; a God damned set of coordinates in the coastal jungle of North Vietnam. It turned out that they would be the last A-6 crew lost in Vietnam.

I think most of the flight crews aboard MIDWAY felt that we had survived the war at this point. It didn’t look like we were going to be doing any of the really scary missions in RP VI for the duration. All we were doing now was ‘marking time’ and waiting for the cruise to end.

On the January 14th, four days after Mondo and Arlo were lost, a VF-161 F-4 was shot down during a daylight mission in the area of Thanh Hoa. The crew LT Kovaleski and ENS Plautz were hit by AAA and were forced to eject. Two days before LT Kovaleski had downed the last MIG in the Air War in North Vietnam. Fortunately, they were rescued following their ejection and didn’t add to the loss board for CAG5.

MIDWAY left Yankee Station on February 8th and headed toward Subic Bay. We were in the Cubi Point Officers Club, when the first POWs arrived at Clark Air Force Base on the 14th of February. As far as I was concerned, this was the ‘End of Our Watch’, and we had accomplished what we had set out to do. The war with North Vietnam was over, and the POWs had been set free.

We had paid a price for this. MIDWAY had lost 30 flight crew members during the cruise. This included both shipboard operations losses and combat losses. Fortunately, six flight crew members from CAG5 were returned as POWs. So the total losses for the ship were around 24 out of approximately 180 flight crew members. The A-rabs had only lost four crew members. I think we had the lowest losses of the other four major squadrons on the ship.

CAG 5, however, had lost a lot of aircraft. Both the Switchboxes and the Rock Rivers (F-4s) had lost a number of aircraft, and at least one of the F-8s was bagged. The A-7 squadrons, who had originally brought 16 aircraft to CAG5, ended up with nearly all new aircraft (replaced) by the end of the cruise. The VA-93 Ravens had all new aircraft, and the VA-56 Champs only had three of their original brood. This is close to 30 A-7s that were lost during the cruise. The A-rabs had only lost 6 or 7 A-6s during the 11-month ordeal.

Post Script: Arlo Clark’s son went on to join the Air Force and become a Thunderbird pilot. An A-6 on the deck of USS Midway in San Diego Harbor is dedicated to Mondo and Arlo.