As I write this post, it is fast approaching 0659 30 December 2012 in Hanoi – 40 years exactly from the end to Linebacker II. President Nixon’s decision – the Linebacker II campaign – in the face of world wide denunciation and in opposition to many in his own cabinet has left NVN militarily “Winchester” – without the SAMs. Indeed Snako noted in Not on My Watch that in his memoirs published in 2007, General Giap, the highly respected leader of the NVA and victor at Dien Bien Phu, included the following quote:

“What we still don’t understand is why you Americans stopped the bombing of Hanoi. You had us on the ropes. If you had pressed us a little harder, just for another day or two, we were ready to surrender! . . . . . . . . “We knew it, and we thought you knew it. But we were elated to notice your media was helping us. They were causing more disruption in America than we could in the battlefields. We were ready to surrender. You had won!”

But they were coming back to the Paris peace negotiations and on the night of 23 January 1973 the President will announce the final aspects of the accords to be signed 27 January. Still combat missions will continue and losses are yet to come. But a huge issue for all of us as we head back for our eighth line period …. the POWs are coming home.

As far as I know the Champs of VA-56 were the only Air Force or Navy squadron to paint POW names under pilot names under the canopy rail as shown here.

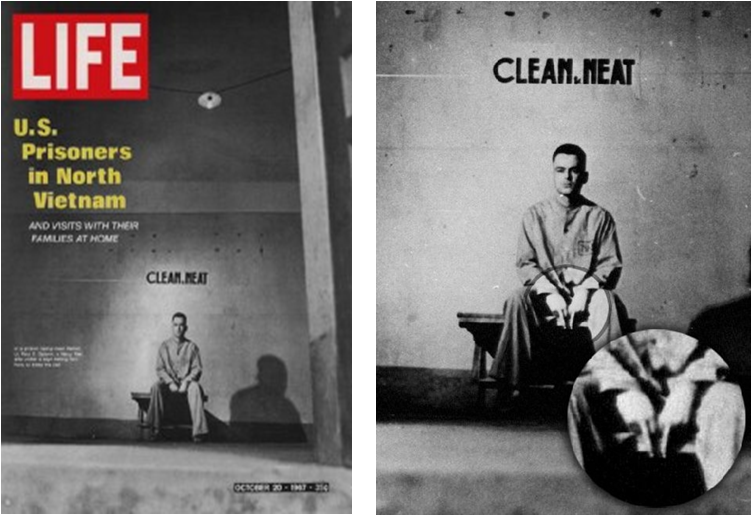

Paul Galanti was one of our squadron CO’s best friends and so his name was beneath Skipper Lew’s on NF 401. No one will ever forget Paul’s picture on the cover of Life Magazine – he was indeed THE MAN. But the Champs were also thinking about our own- Al Nichols and Mike Penn – plus- the other CAG 5 POWs.

We discussed previously the apparent differences and knowledge of Linebacker II based on whether being out on Yankee Station or at one of the multiple airfields the Air Force used in Thailand, but there was another perspective – what if you were at the Hilton? What did the Fourth Allied P.O.W. Wing know? What were they thinking? As preparations began for that very first night of LB II, the thoughts of Ed Rasimus from his book Palace Cobra are telling.

Palace Cobra Chapter 10 -Christmas Cards to Jane and Ho

Palace Cobra Chapter 10 -Christmas Cards to Jane and Ho

by Ed Rasimus

Jack Van Loan (Maj. Jack Van Loan was shot down on 20 May 1967, flying the wing of Col Robin Olds in an epic air battle near Kep airfield in which six MiGs were downed. He returned 4 March 1973) had been in jail since 1967, and it was now 1972. Recently I asked him about the view from his cell; he related this tale:

It was a quiet afternoon without too much going on when here comes a raid of some kind which everyone in the room was ignoring. We had about 35– 40 cons in the room and down at one end playing bridge was Jim Young, an F-101 Recce driver and three other guys. The raid went on and finally it became apparent when the guns stopped and the SAMs stopped that the MiGs and the F-4s were dogfighting right over the top of the prison. One of the tricks used by both our guys and the bad guys was when you got an adversary trapped at dead six, drop down to tree top level and haul ass right over the center of the city. That got everyone with an AK shooting straight up and guess who got shot?? Of course, the number two guy— the chaser.

Well anyway, I am sitting there when all of a sudden there is a brief whistling noise and then this F-4 goes by going super plus and there is an enormous clap of noise with stuff lifting off the ground, including me, and over where Jim and his guys are playing bridge this huge piece of plaster about the size of a blanket breaks loose and down it comes right over Jim. He doesn’t even look startled but has blood running down his face from some cuts on his head. Without skipping a beat or even acknowledging the boom, the blood or the blasted plaster, he leans forward and with no emotion says, “four hearts.” That’s when I realized we had been there too long!!

It’s impossible to comprehend, no matter how many times you sit and listen to the stories, the perspective of the war for the POWs. They were captured in late 1964, and ’65 and ’66. They came from F-100s and -105s, F-4s and A-4s, F-8s and (A-7s), A-6s, from the Air Force and the Navy and the Marines. They went to war when patriotism was a virtue and courage expected. They did what was asked of them without for a moment questioning whether their country would come to get them when things went awry. They were tortured and paraded, beaten and interrogated, but most of all they were disappointed.

and courage expected. They did what was asked of them without for a moment questioning whether their country would come to get them when things went awry. They were tortured and paraded, beaten and interrogated, but most of all they were disappointed.

It must have been a support for their hardships as each day they heard the sound of freedom overhead, jets attacking the critical targets in the North Vietnamese homeland. They got reinforcement to face their captors by seeing airplanes and listening to the bombs and the defensive reactions. They got occasional news through the tapping on their cell walls as they resisted with every fiber of their being their torturers’ demand not to communicate with each other.

Then, in the late summer of 1968, it got quiet. This had to be crushing to morale. What had happened? Why wasn’t the war going on anymore? Was anyone thinking of them or trying to gain their freedom? Were they abandoned? They had faith and confidence, but there had to be doubt and discouragement.

Three and a half years— years!— later, there were airplanes overhead again. There was jet noise again, and bomb blasts and SAM launches and flak barrages. There were new arrivals with news of America. In April and May of ’72, it must have seemed that at last there might be hope of freedom. For six months they were hopeful once more. Pressure was being placed on the North Vietnamese, and maybe victory would come soon.

Then, in late October, it stopped again. What now? Is it more cruel to dangle freedom and withdraw it without explanation than simply to never offer the slightest hope?

…. The second night of the campaign, the B-52s returned with three more waves of bombers. 3 Recce photos showed both the damage and the precision of the campaign. Bomb strings from the huge aircraft walked across the targets and carefully seemed to sidestep residential areas or designated off-limits compounds. Intelligence information on probable POW compounds was put to good use, and while we may have joked about dropping one on Jane Fonda, we were well aware that a lot of our friends had front-row seats for the battle that was going on.

Jack Van Loan and many of his friends had been moved out of Hanoi early during the Linebacker campaign. They had been transported out of the city in mid-May to a new camp they dubbed Dogpatch, near the Chinese border. Some said it was an attempt to break up the cadre of senior resistance leaders among the POWs. Guys like Jack Van Loan, Robbie Risner, Paul Galanti, Larry Guarino, and others had been well organized, and with the commencement of Linebacker, they were working hard to integrate the new arrivals to the POW camps into their organizations. Maybe it was breaking up the leadership, or maybe it was a way of protecting the North Vietnamese bargaining chips at the peace talks. Either way, they were going to miss the show.

Dave Mott, on the other hand, was still in the center of town. 4 He had been at the Hoa Lo prison, the infamous Hanoi Hilton, from shortly after his capture until early December. Then he was moved, in apparent anticipation of a possible rescue effort similar to the 1970 Son Tay raid, from Hoa Lo to the smaller Plantation in the northeast section of Hanoi. With rudimentary hand tools, they were ordered to dig bomb shelter trenches in their cells under their rough board beds, large enough to crawl into in the event of attack. The similarity in size between a sheltering trench and a man-size grave was not lost on the prisoners.

With the first strikes, it quickly became apparent to POWs in the capital that things were coming to a conclusion. The bombing intensity, the night defensive reactions, even the flaming wreckage of the big bombers that had been hit overhead, all served to let them know that someone at last was getting serious about ending the war. The bombs were close, but everyone in the prison compounds knew the business. They knew that we knew they were there, and they knew the difficulty of hitting targets when the defenses were up. Photos of suspected POW camps were posted in intel, and several of us took coordinates on missions and made attempts to overfly the camps and maybe get the message through that we knew where they were and wouldn’t hit them.

From the Plantation, Mott could only see outside by standing on the boards of his rough bunk and straining to reach a corner of the high, small window. From there he could see the flashes of the airbursting flak and the bright fire trails of the SAMs. From there he could catch the tumbling fireballs of the B-52s that were hit, and see the flames’ reflections in the chutes of descending crewmembers who were able to eject. There would be company in camp in a day or two.

Ted Sienicki was at Hoa Lo when Linebacker II kicked off. It didn’t take long before the camp’s propaganda operatives were broadcasting statements from Americans over the radio, complaining about the “nearness and intensity of the bombing.” The prisoners couldn’t tell the source of the statements, whether they came from the few collaborators among the otherwise tight-knit POW community, or maybe from an American politician or antiwar activist, but the reaction was immediate. It couldn’t possibly be close enough or intense enough.

Our dream was to someday soon hear silence, peer over the glass-embedded, stone-capped high walls, and see the Gulf of Tonkin, ’cause the city was fucking bombed away. We laughed at that statement for the rest of our tour, and it became the phrase of choice to indicate when somebody was whining or being a baby, poor sport, whatever. Oh, dear, the bomb is too near and too intense. One day, a bomb exploded closer than ever. We weren’t hurried in from outside, as we usually were; the raid was a surprise with little warning. A softball-sized jagged piece of shrapnel flew by me at great speed, and bounced along the cobblestone and slate floor. Impressive. It was nice to finally feel like a ground troop.

Sienicki’s reaction wasn’t fear, but hope and enthusiasm. “I never worried about bombs being too close. Neither did anybody I knew. But one guy, upon learning from a B-52 crewmember who arrived in camp that SAC was using the Hilton as an offset aim point, wondered aloud how many times he or others simply forgot to press the offset button!”