Testimony of Pilot #31

Once at a dinner party I was asked by a woman what on earth I had ever seen in military life. I couldn’t answer her, of course.

I couldn’t summon it all, the distant places, the comradeship, the idealism, the youth. I couldn’t tell about flying over the islands long ago, seeing them rise in the blue distance wreathed in legend, the ring of white surf around them… I couldn’t tell about Mahurin being shot down and not a soul seeing him go… I couldn’t tell her about brilliant group commanders or flying with men who later became famous, the days and days of boredom and moments of pure ecstasy, of walking out to the parked planes in the early morning or coming in at dusk when the wind had died to make the last landing of the day …

To fly with the thirty-year-old veterans and finally earn the right to lead yourself, flights, squadrons, a few times the entire group. The great days of youth when you are mispronouncing foreign words and trading dreams.

Money meant nothing and in a way neither did fame. I couldn’t tell any of that or of the roads along the sea in Honolulu, the dances, the last drinks at the bar, or who Harry Thyng was, or Kasler, or the captain’s wife. James Salter, Burning the Day

Collected years ago, probably from a Sunday Magazine …

Flight Into Remembered Sky

By Thomas French Norton

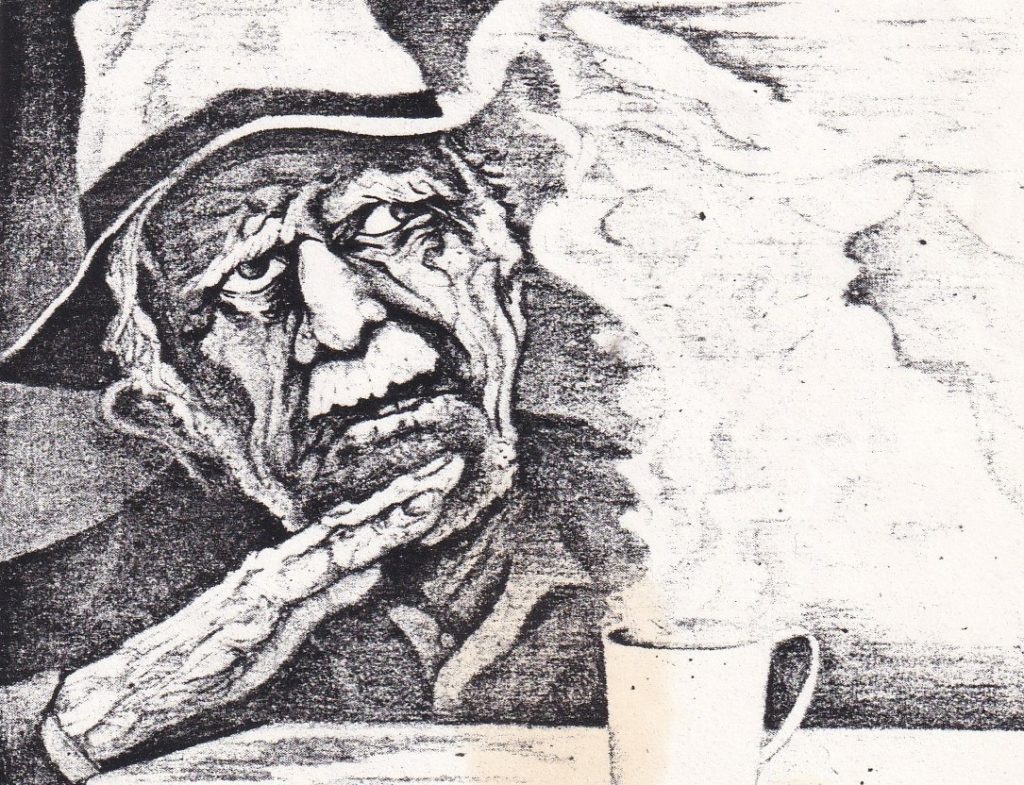

He didn’t look like the ordinary street bum.

He didn’t look like the ordinary street bum.

Perhaps it was his eyes, which were clear and blue and focused on some distant horizon. Or his stance. He carried his head up and his shoulders squared. He needed a shave, but he wore a white military mustache thar had seen recent trimming.

Our eyes met for a moment and some kind of recognition passed between us.”Could you spare something for an old B-24 pilot?” he asked.

He had been a tall skinny kid of 20 when he joined the Army Air Corps in 1943. He was sent to Texas, where he went through flight school. It was hard work, he said, but it was exciting and it gave his his first real purpose. He loved every minute in the air.

Graduation day came and he got his silver wings. He had never been prouder. He was assigned to fly B-24 bombers. In them he flew every day, hour after hour polishing his skills, learning evasive action, learning that you had to stay calm in the cockpit no matter what the instructor did to surprise you. Staying calm was important. If you stayed calm, you didn’t make dumb mistakes. You stayed in control. He liked that.

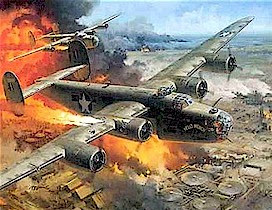

Eventually, the day came when the class of highly trained pilots and crews left Texas to fly across the Atlantic to Libya. They got a tough assignment. First, it was Italy, which the Krauts were defending with great fervor. Then it was the Romanian oil fields.

He flew 52 missions over Ploiesti and a lot less-publicized towns, blasting refineries and storage tanks and fields full of oil well pumps. You could just about walk on the flak, it was that thick. And Hitler needed that oil pretty badly, so he sent his best fighter to defend it. How many friends went down over Romania, to sit out the war in a prison camp if they were lucky, or to end their lives in a fiery crash if they weren’t? he couldn’t count them. He didn’t want to know.

There was never enough rest between missions, never enough time to think about it all and try to get it straight in his head. The days were filled with briefing and flying and praying your wasn’t on one of the German shells, and flying and sweating some more, and debriefing and grabbing a mealand sadly looking down the casualty list and going to bed for a few hours before it all started again the next day, long before dawn.

Eventually it came to an end. He came home to a hero’s welcome. He figured he had a future in aviation, since everyone was saying that flying had a great future. And that was all he wanted to do: to keep flying.

It wasn’t that easy. Tens of thousands of pilots were flooding the market. And peacetime flying was different. He took jobs all over the place; jobs instructing a lot of GI Bill ground-pounders who had looked up from the foxholes and thought flying was romantic; jobs flying freight, flying groups of sightseers, even flying big-city newspapers to outlying cities. He was flying, but there was no sense of mission. He went through a lot of these two-bit jobs, and he went through two marriages, as well.

He couldn’t make ends meet as a pilot, so he took other jobs, always telling himself that they were just to see him through until he could fly again. At first they were desk jobs and some of them paid fairly well, but a desk wasn’t an airplane cockpit and the jobs weren’t interesting and he found it harder and harder to concentrate on what he was being paid to do. He started drinking, which – unlike a lot of pilots he had never done while he was flying regularly.

The desk jobs gave way sales jobs and then to laboring jobs. He couldn’t understand what had happened. The ghosts of World War II haunted his head. It had been, he said, the one important thing he had ever done. It had been real. It had been man’s work, he said. Fighting for a good cause and for your own life, that was some kind of basic manly instinct and all the rest was just decoration.

We sat in a coffee shop and talked for an hour, maybe more. As he told me his story, his right hand would instinctively to a fistful of throttles and he would move them smoothly and professionally. Or he would punch an imaginary microphone button with a finger that still remembered how a B-24 wheel felt through a leather flying glove, and where the mike button was. Talking about losing an engine, he reached up and forward to where the feathering button dwelt in his memory.

He spoke of places and airplanes and companions, of battles and feelings, of people and events, as though they were yesterday’s memories and not half a lifetime away. It was all very real to him.

After all, it was the only important thing he ever did.

____________________________________________________________

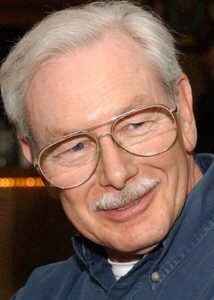

Tom Norton, former General Aviation News editor

Tom Norton, former General Aviation News editor

Feb. 23, 1934 -Dec. 2, 2011

Tom was well-known in aviation circles for his encyclopedic knowledge of aircraft.

He was a retired Naval Aviator, having spent 31 years flying A-4s in the Naval Reserves after serving in Vietnam. He was also an attack squadron commander and training officer, “turning nuggets into Naval Aviators,” he used to say.

He then worked for the American Film Institute at the Kennedy Center. Later in his career, he was the editor for the Skipper Magazine, the Southern Aviation News and finally for General Aviation News. “In the last year and a half Tom had been on the airport board at Easton/Newman Field Airport (ESN),” said Anna Norton. He had joined General Aviation News’ parent company Flyer Media in 2001 as editor of the now-defunct The Southern Aviator and writer for General Aviation News. he was a mainstay at air shows and fly-ins like Sun ’n Fun and Oshkosh.

Tom was born into an aviation family. His mother, Catherine Medary, and her three sisters, Mary Lou, Patti and Juliet, were among the first women in the United States to earn their private pilot’s licenses. All four earned their tickets Oct. 4, 1929. They were known as the Flying Sisters of Philadelphia. Tom used to tell that his family always had airplanes, and used them like most people use their cars.

Tom took his first flight with his mother in 1939 when he was 5 years old. “She had a prewar Luscombe, a Model 8 Silvaire, and she took me everywhere in it,” he said. “That was the first airplane that I controlled myself at the age of 11.”

Tom earned his private pilot’s license in 1950. Ironically, the first time he took his mother for a ride, they ran into trouble. “We were in a Piper Tri-Pacer and when we were on downwind the damn thing swallowed a valve,” he said. “We were able to land safely, but it was embarrassing. Mother was very calm, much more so than I.”