Testimony of Pilot # 29

‘Dogfighting makes movies. Close air support wins wars,’

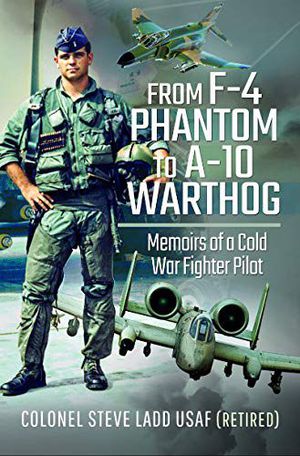

Colonel Steve Ladd (USAF, Ret) recently published From F-4 Phantom to A-10 Warthog; Memoirs of a Cold War Fighter Pilot, and has graciously provided RememberedSky with a key excerpt particularly pertinent to RS’s major thread of air-ground or attack missions recently catalogued and highlighted in the post Anthology – RememberedSky Vietnam Airwar ’72-73 Stories.

Note that definitive of US Air Force usage, despite half of Steve’s 4000+ hour career in the A-10 attack aircraft, he refers to himself as a fighter pilot, and indeed in both the F-4 and A-10 aircraft his squadrons were Tactical Fighter Squadrons.

Note that definitive of US Air Force usage, despite half of Steve’s 4000+ hour career in the A-10 attack aircraft, he refers to himself as a fighter pilot, and indeed in both the F-4 and A-10 aircraft his squadrons were Tactical Fighter Squadrons.

The Air Force and the aviation branch of the U.S. Navy have similar roles and missions but have distinct differences, mostly (but not all) of course driven and centered around the aircraft carrier.

Historically, through WWII navy squadron designation indicated their mission – VB, dive bombers, VT-torpedo bombers, VS, scouting and dive bombers, and VF, fighter or air-air. In the 50s the VB/VS/VT consolidated under the nomenclature “VA” for attack, air-ground missions. This remained until the replacement of both F-4s and A-7s by the F/A-18 Hornet with squadron designation becoming “VFA,” strike fighter squadrons, tasked to do both air-air and air-ground. From the Air Corps/Air Force perspective in the 30s the decision was made to not design, purchase, or designate “A” attack a/c. They did violate their rules with the A-1 Skyraider, A-7D, and the A-10, and thus they had Tactical Air Command fighters and Strategic Air Command bombers (strategic bombing tasking – B-17, B-29, B-52, etc).

And so, considering first the air-ground mission and then differences in the two services, and terminology, Col Ladd’s career experiences are of great interest in regard to the focus of RememberedSky and so…

OBTW, really well written and highly recommended!!!

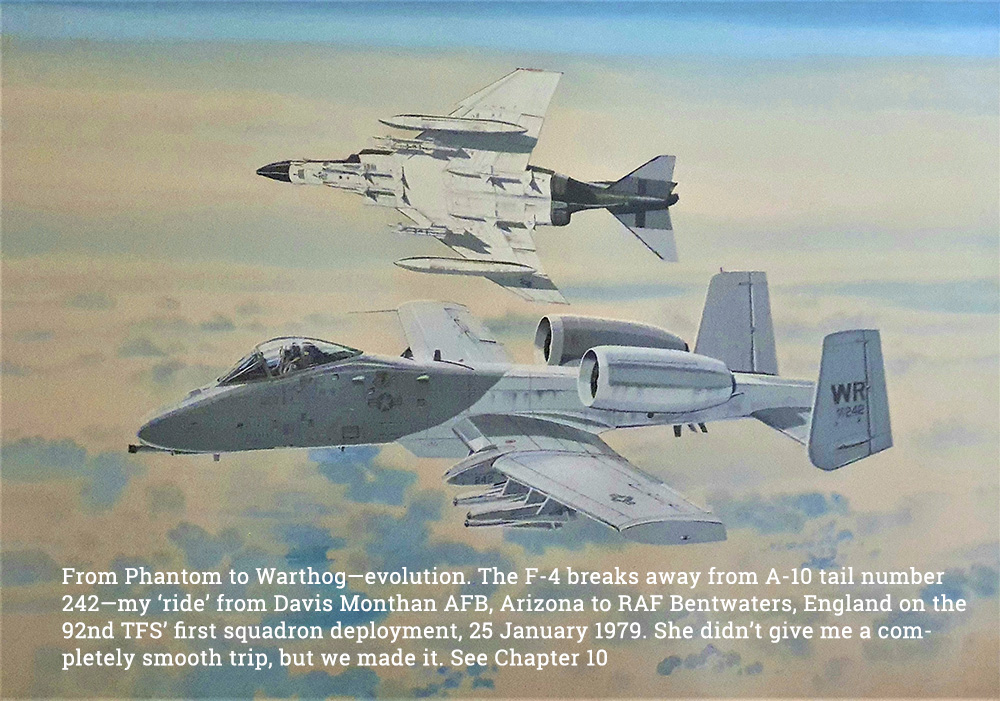

PHANTOM TO WARTHOG – The Transition

In 1978, the Air Force announced that 81st Tac Fighter Wing Phantoms would be relaced by the A-10. While I was merrily proceeding with my mental plan to follow the F-4 wherever she would take me, my former backseater at Torrejon dropped by for a visit. Ed Thomas had been an F-105 Electronic Warfare Officer (EWO) in the Wild Weasel program in South-East Asia. These guys went hunting for North Vietnamese surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and used sophisticated acquisition equipment and beam-riding missiles to locate and exterminate the SAMs. The mission was dangerous but rewarding and relied heavily on the technical skill of the EWOs (known universally as ‘Bears’) to achieve successful outcomes.

When Ed left South-East Asia, he transitioned to the F-4 back seat and ended up with me as a formed crew (bringing the ‘Bear’ nickname with him). We bonded immediately; he had my total respect as a professional and as a drinking buddy and confidant. As happens less often than it should have in the Air Force, the Bear’s talents were finally acknowledged, and he was selected to go to pilot training. He departed Spain shortly after we did and a couple years later was flying the single-seat LTV A-7 Corsair in the close air-support role. Therein lies the reason for including this anecdote.

I brought him out to the house on a Friday evening, where Elaine had prepared dinner and we all had a lively chat about old times with the ‘Spanish Flyers’ – parties, road trips, mutual friends and foes and flying.

– notably the time we (oh, all right, ‘I’) dropped a 600-gallon centerline fuel tank on a Spanish gunnery range instead of the intended 25lb smoke bomb.

The hour grew late, the single malt whisky appeared and Elaine decided we were becoming unintelligible and she would leave the boys to their own devices. The conversation moved entirely to aviation. I told the Bear about the impending transition and gave him all my logical, painstakingly reasoned and compelling arguments on why I would be snubbing the ’Hog in favor of a few more years of flying Phantoms. The ’Hog was slow, the ’Hog was terminally ugly, the ’Hog failed to support my enthusiastically-cultivated image as a dashing fighter pilot; I would be mortified to climb out of this ungainly beast at a strange airfield. Having run out of logical, painstakingly reasoned and compelling arguments and lubricated with another double shot of Glenlivet, I started the list all over again.

Although he, too, only had a basic working knowledge of the A-10, his argument was cleverly constructed around a number of factors near and dear to the heart of a fighter pilot and robustly supported by the magic of Glenlivet. Why, he asked, would I want to continue to fly in an airplane with a built-in backseat passenger when I could be master of all I surveyed in the single-seat ’Hog? Without directly referring to yours truly, his former FUF (Fuckhead Up Front) he lauded the delights he had discovered since earning his pilot’s wings and subsequently swapping me for a couple of hundred pounds of JP4 jet fuel to venture forth in the land of single seat flying.

>>> He then switched his argument to the mission: the F-4 had been the consummate Jack-of-all-trades and he, like me, enjoyed the variety that role provided. Since joining the single-mission close air-support world, however, he had found genuine satisfaction in specializing and becoming very, very good at a single, complex and demanding mission. Close support of troops on the ground brings with it a powerful element of responsibility: that of delivering lethal weapons in very close proximity to those friendlies you are supporting and the unparalleled sense of achievement that follows when you’ve whacked some bad guys and saved friendly lives.

>>> It’s not completely noble in nature, however. The Bear went on to remind me of the somewhat selfish benefits of getting close to your work in an attack aircraft and getting instant feedback on your performance. ‘Dogfighting makes movies. Close air support wins wars,’ he said, and I started to believe him, although I have no doubt that there is job satisfaction in hurling an air-to-air missile at an enemy which is visible only as a blip on the radar screen many miles distant, and even a bit more when that blip goes ‘poof ’ and disappears, alleging a kill.

>>> That admittedly lofty level of video game feedback cannot compare with the air-punching elation that comes with rolling in on an armored column. You ignore the incoming tracers whizzing past in your peripheral vision, put the gun cross on an advancing tank a mile or so distant, squeeze off a few rounds and watch said tank explode as a combat mix of armor-piercing and high-explosive incendiary 30-millimeter rounds drives home and detonates. That, ladies and gentlemen, is feedback at its very best and this was the prospect the Bear laid out before me as night transitioned into dawn.

I was a beaten man. My old friend the Bear had left my feeble line of reasoning in tatters and by the time I had recovered from my raging hangover, my chosen career path had been irreversibly altered and resolved. ‘We’ came to a splendid decision that night. Thanks again, Bear; I owe you another one.

Firmly persuaded, I strolled into our Base Personnel Office on the Monday and signed over my hard-earned entitlement to awesome power, blazing speed and the admiration of fast jet aficionados the world over in exchange for a 350-knot airplane that sounded like a huge ceiling fan and looked very much like a slug with wings.

It would be quite a while before I appreciated exactly what I gained when I signed that upgrade (downgrade?) request.

As there were no A-10s based in Europe when we transitioned from the F-4, our first glimpse of the ’Hog came when we arrived in Tucson for training. We were taken aback by the size of the airplane, not necessarily because of sheer length, width or girth; more in terms of how conspicuous a target we were going to be lumbering slowly around the sky in this behemoth.

Virtually all Air Force flying training courses follow a similar profile. There’s always a certain amount of ground-based academic training required before they let you anywhere near an airplane and the A-10 course was no exception. We were quite amazed at the simplicity of the Warthog. Having flown a fighter developed in the ’60s for many years, we were acquainted with outdated technology but at least there was some technology to be acquainted with. The A-10 in most respects appeared to be a Second World War machine, tarted up with two fanjet engines. These didn’t seem to have much effect on the speed of the bird, but at least no one had to prime propellers to get it started.

The good news here was that pre-flying academics were relatively benign. The airplane was simple, operating systems and limitations were straightforward and, compared to learning the idiosyncrasies of the Phantom, getting ready to climb aboard the ’Hog was a piece of cake. What gnawed at us all a bit (although none of us would ever own up to it) was a slight twinge of apprehension about the crew configuration on the first hop. There were no two-seat training versions of the A-10 with space for a guardian angel to ride along. As much as we were exhilarated by the prospect of flying a single-seat fighter, none of us had ever taken a first flight in an Air Force aircraft without an instructor pilot in a second seat, just in case. This applied to all three pilot training birds and every aircraft thereafter. As motivated, confident and yes, arrogant as we all were, there was a small seed of ‘What if ?’ lurking inside us. While the instructor didn’t exactly just ‘plug in a microphone and run along outside’, he’d be chasing us in another aircraft and therefore unable to provide much more than verbal technical (and moral) support.

While we were busy getting accustomed to this kind of Second World War-era technology, another subtle and insidious event was taking place. We began to learn a bit more about the Ugly Duckling we were inheriting, and what was at first a slightly grudging acceptance of some of the less glamorous features of the aircraft began to grow into something much more substantial.

The folks that designed the ’Hog were well aware, as we all were, that an aircraft that big and that slow was going to take hits in a combat environment. It began to dawn on us that our little tantrums regarding the appearance of our new steed were a bit unfair and maybe, just maybe, there were some very positive features we were ignoring while focusing on the aesthetics, or lack thereof.

For example, the two enormous fanjet engines apparently added as an awkward afterthought to either side of the aft fuselage had one or two redeeming features: these were relatively quiet and bad guys with AK- 47s were unlikely to hear us coming until it was too late to react. They burned much cooler than conventional turbines and were therefore far less susceptible to ground-launched heat-seeking missiles. Indeed, the awkward positioning of the engines just forward of the twin vertical tailplanes meant that the reduced heat signature was actually shielded by these appendages, further reducing our heat ‘signature’ and lessening the risk of being tracked by a heat-seeker. Finally, unlike other jet’s engines snugly enclosed in the airplane’s fuselage, they could be readily swapped right to left or vice versa if damaged. This capability to ‘switch hit’ also applied to the main landing gear, primary aircraft flight controls – ailerons, rudders and elevators – and many external aircraft panels. This unique versatility proved invaluable in later years when aircraft parts were commonly switched back and forth to repair battle-damaged birds in the Gulf War and subsequent mêlées.

As I mentioned earlier, the aircraft was fitted with wheels which protruded slightly beneath their housings rendering them aesthetically repugnant and therefore of no real value. Au contraire! I was forced to recant when I learned they were designed that way to lessen aircraft damage from a wheels-up landing necessitated by battle damage or hydraulic catastrophe. If that wasn’t impressive enough, the quirky landing gear retracts forward. Why? Without hydraulic pressure, you can unlock the gear and the combination of gravity and your headwind will help them fall into place and lock down. Oh, me of little faith!

We made more significant discoveries while we were checking out in the airplane. We were, for example, riding around on 1,200lb of molded titanium known as the bathtub. This handy bit of kit was inserted there to protect vulnerable flight control cables, fuel hydraulic and electrical lines and other components from ground fire. The most vital of those components, in my book, is my chubby pink ass and the reduced probability of being disemboweled by some Jihadi’s AK-47 round clearly trumped the flak we often caught from F-16 and F-15 drivers: ‘Going out to take another bath today, Steve?’ It was best to ignore the taunts; mincing ballerinas, all of them.

The fighter pilot’s worst nightmare, other than a fire in the cockpit, was that ‘golden BB’ (lucky shot) that penetrates the main hydraulic lines and freezes up all your flight controls with only a ‘step over the side’ option remaining. The ’Hog was designed with numerous features, not one of which improved its appearance (I keep coming back to this; what a pompous bastard I was) but instead were installed to bring us back alive from a thoroughly unpleasant outing in some Cold War or Middle Eastern shooting gallery. A few of them are outlined below.

Fighter aircraft have had dual flight control systems for a long time, but prior to the A-10 they were designed to compensate for system failure and consequently weren’t physically separated. The engineers who designed the ’Hog thought to themselves: ‘Man, the bad guys are going to beat this big, slow airplane like a red-headed stepchild; how can we get it home in one piece?’ so they set about fitting separate and distinct flight control channels on opposite sides of the aircraft which couldn’t both be taken out by the golden BB. Control inputs are transmitted to the flight controls by cables rather than the traditional rods. They are less likely to be taken out by a single bullet or jammed by structural damage. As noted above, the dual control systems are physically separated to further lessen the likelihood of catastrophic failure due to ground fire. Either system can be locked out from the cockpit, enabling degraded but controllable flight. If the proverbial shit really hits the fan, the last port of call is the manual reversion system, which provides limited control inputs to small trim tabs on the flight controls in the case of no hydraulic boost whatsoever.

Similar survival-oriented thinking went into the fuel system. Except for benign ferry missions, all fuel is carried internally. Fuel lines are protected by running them through the tanks and those tanks are lovingly cared for: they are tear-resistant, self-sealing and fitted with folded flame- resistant foam panels which expand when the tank is breached to limit fuel spillage and airflow to the damaged tank.

All the while we were learning about the survivability features the ’Hog afforded, we were undergoing a subtle but undeniable mental metamorphosis. Our going-in position of ‘I don’t want to be seen anywhere near this dreadful collection of bumps, lumps, angular irregularities and grotesque features’ was gradually being replaced with the steady emergence of an entirely different attitude. There was no denying it, flying this airplane was kicks and the more we sampled the instantaneous control responses, spectacular roll and turning capability, magnificent external visibility and efficient radio communications equipment, the more we began to appreciate the ’Hog (or, dare I say it, be seduced by her). Our training, as always, was a stair-stepped approach and, although it was sandwiched into a short period of time, the basic simplicity of flying the bird allowed relatively rapid progression. It wasn’t long before we had all mastered the nuts and bolts of getting it into the air and getting it back down again, at which time we were able to work on the fun stuff in between those two important events: employing the Warthog tactically. This involved another progression, first involving missions to the Air Force’s gunnery ranges to explore and then perfect our weapons delivery skills. In almost all respects, this phase of training was very similar to weapons programs in any other tactical fighter capable of delivering air-to- ground weapons. We carried weapons dispensers, each with six cute little 25lb blue bombs fitted with charges which discharged equally adorable little puffs of white smoke on impact. These puffs could be plotted on the target we were aiming at on the ground and a score provided; instant feedback (and something we could bet on within the flight – big stakes, normally – a quarter a bomb).

Note I said that the training was comparable to any other weapons programs in almost all respects. There was one significant difference. Shoehorned under our titanium bathtubs and occupying most of the fuselage real estate between nose and trailing edges of the wings is the most fearsome forward-firing weapon ever mounted in an aircraft. It was officially designated the Gun, Aircraft Unit (GAU) 8 Avenger. We just called it…

>>> The GUN! <<<

I’m not going to reel off dozens of technical specifications; Google ‘GAU-8’ if that’s what you’re looking for. No, I want to tell you what it does, how well it does it and how it makes us feel to pull that trigger.

When we were introducing the ’Hog to Europe, we often briefed NATO Military and European political leaders and we never failed to impress with a comparison photo involving a Volkswagen Beetle. This was a graphic demonstration of the dimensions of the Gun. The large cylindrical drum at the rear holds 1,170+ linkless rounds, which are cycled into the firing mechanism: a seven-barreled Gatling gun arrangement. After firing, the empty casings continue the cycle back into the drum so spent rounds are not ejected from the aircraft.

In my day, the GAU-8 was optimized to fire 4,200 rounds per minute (that’s 70 per second for those of you who are math dunces; don’t get upset at the label as I am among you). It has since been limited to 3,900 rpm, but let’s discuss the Gun at its peak.

The ultra-clever among you will have already noted the disparity between rounds carried (1,170) and 4,200 rpm. You are correct, but when you’re hurling seventy 30mm projectiles weighing just over a pound per second at a hapless enemy tank, size matters more than numbers, hence my comment above about the lack of necessity for prolonged bursts. Tests indicate the GAU-8 will routinely put around forty of those seventy rounds smack dab in the middle of a vehicle, unquestionably ruining a tank crew’s day in less than the blink of an eye.

These projectiles aren’t just long-neck beer-bottle-sized hunks of metal either. Going to war in the ’Hog means saddling up on a combat mix load of five armor-piercing incendiary (API) rounds to one high- explosive incendiary (HEI) projectile. The API rounds are the much- maligned depleted uranium rounds which are actually less radioactive than the average shovel full of earth from your garden, but have received lots of bad press simply because no one thought to call them something else.

The API rounds are designed to punch large holes through the substantial armor of a tank, followed in very close proximity by HEI.

This does an excellent job of ricocheting around the interior of a tank, causing the crew, in their very last thoughts, to wish they had become insurance salesmen.

The Gun is optimized to fire most accurately at around 4,000 ft from the target. This range is less important than it is for many guns because the extremely high velocity of the GAU-8 round when it leaves the barrel and the weight of the round mean they don’t decelerate rapidly. This results in a flat trajectory and an exceptionally accurate firing solution well beyond the optimum 4,000 ft.

At the same time we were integrating the airplane into the European Theater of Operations, the charisma of the ’Hog had begun to proliferate in bigger ways. Army commanders, witnessing the airplane’s performance in gunnery demonstrations and live fire displays could be heard extolling the virtues of the A-10 as a troop support weapons system. She had the ability to keep pressure on an enemy through lengthy loiter time, pinpoint weapons delivery accuracy and an impressive array of munitions, not the least of which was that crowd-pleasing Gatling gun. The grunts who would benefit most from the A-10’s act began to appreciate what we could do for them during various exercises which combined infantry and armored operations with close air support. Their enthusiasm would later reach a crescendo during the Gulf War (DESERT STORM) and subsequent skirmishes but getting used to the ’Hog took some time, for them as well as us.

>>> I was to spend the next 9 years flying the A-10 and I’ve never looked back The F-4 was magnificent and will always be a very slight favorite in my book, but the A-10 is only inches behind. The attack role is beyond a doubt the most challenging of all and the Close Air Support element provides the ultimate in testing the pilot’s skill and flexibility and providing job satisfaction.

To think I almost turned it down!

Colonel Steve Ladd, DFC, MSc, BSc was a career USAF officer, fighter pilot and commander for 28 years. During his career, he amassed over 4400 hours’ flying time, equally split between the F-4 Phantom and the A-10 Warthog. His Phantom credential includes over 400 hours (204 missions) of combat experience over North and South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

Colonel Steve Ladd, DFC, MSc, BSc was a career USAF officer, fighter pilot and commander for 28 years. During his career, he amassed over 4400 hours’ flying time, equally split between the F-4 Phantom and the A-10 Warthog. His Phantom credential includes over 400 hours (204 missions) of combat experience over North and South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

Since retirement from the USAF he has been employed as a CAA Aerodrome inspector, Operations Director of Cardiff International Airport, Fast Jet Curriculum Development Lead for Ascent Flight Training, Ltd., and adjunct Professor of Aviation Science and Management at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. Colonel Ladd and his wife of 47 years live in Bristol, England.