Blown Slick Series #13 Part 14 (3/4)

“It is true, Marines will take a pounding until their own air gets established (about ten days or so), but they can dig in, hole up, and wait. Extra losses are a localized operation. This is balanced against a potential National tragedy. Loss of our fleet or one or more of these carriers is a real, worldwide tragedy.” Colonel Melvin J. Maas, USMC TF-61 Staff

TF-61 at Guadalcanal: three of the for carriers in the Pacific in August 1942 – Wasp, Saratoga, and Enterprise.

In a series on carrier operations at the beginning of WWII it would be remiss not to discuss the controversial decisions made by VADM Fletcher concerning withdrawing his TF-61 carriers from the immediate vicinity of the attack after the initial landings. The basic role of the carriers in the Watchtower landings was, of course, to provide air support, in particular fighter cover.

This piece is not intended to cover the events in detail but only to provide basic context in the early evolution of carriers in warfare. In hindsight it is useful to reflect on two items: 1) TF-61 was composed of three of only four US carriers in the Pacific and 2) it is well worth highlighting how much the rough parity of carrier forces of the two sides contributed to the protracted nature of the overall bloody struggle for the island.

Withdrawal of the Carriers

Early in the evening of August 8, in his flagship McCawley, Admiral Turner was wrestling with the frustrations, minding the possibility of further attacks on his transports, when Frank Jack Fletcher did what Turner had been dreading for two weeks. In a message to Admiral Ghormley, Fletcher was requesting permission to withdraw his three aircraft carriers, now serving as his Task Force 62’s umbrella and shield, from their supporting positions near Guadalcanal, so that both his carriers and supporting destroyers could refuel, but also to move the carriers to a position “unleashed” from the island environment itself.

Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, commander of Task Force 62 (left), and Major General A. A. Vandegrift, USMC, commander of the 1st Marine Division, working on the flag bridge of USS McCawley (AP-10), at the time of the Guadalcanal-Tulagi landings

Fletcher’s critics

To Fletcher’s legion of critics message 080707 of August 1942 defined his naval career. In 1943 Turner bitterly complained to Morison that Fletcher left him “bare-arse.” In 1945 he officially characterized the action as nothing less than “desertion,” undertaken for reasons “known only” to Fletcher. Vandegrift described Fletcher, “Running away twelve hours earlier than he had already threatened during our unpleasant meeting.”

Official judgments were equally unsparing. On 23 August 1942 Nimitz condemned the withdrawal as “most unfortunate,” a comment he repeated in The Great Sea War. In December Admiral Pye, president of the Naval War College, called the pullout “certainly regrettable,” which risked “the whole operation.” In 1943 Admiral Hepburn’s final Savo report labeled Fletcher’s action a “contributory cause of the disproportionate damage” incurred in that battle. The Cominch Secret Information Bulletin No. 2 gave short shrift to the reasons attributed to Fletcher’s decision, including needless worry about “bombing and torpedo planes.” The 1950 Naval War College analysis of Savo expanded on Pye’s original points and concluded, “Such a precipitous departure” would “seriously jeopardize the success of the entire operation” and “prevent the inauguration of Task Two.”

Historians accepted the official judgments without question. Morison wrote, “It must have seemed to [Turner] then, as it seems to us now, that Fletcher’s reasons for withdrawal were flimsy.” The carriers “could have remained in the area with no more severe consequences than sunburn.” Marine Brigadier General Griffith, historian as well as participant, completely concurred. He conceded, “Fletcher did have a point. We just couldn’t lose our carriers, but damn it, how the Marines suffered!” Vice Admiral Dyer did present Fletcher’s side, but his sympathies lay with Turner. The situation did not justify the carrier withdrawal. That was also the carefully considered judgment of Richard Frank, who concluded Fletcher, rightly or wrongly, placed the preservation of his carriers ahead of everything else. All other accounts derive from these key analyses.

Fletcher’s Dilemma

VADM Frank Jack Fletcher was the most battle-seasoned senior officer in Operation Watchtower. The experience of combat had taught him its costs. At both Coral Sea and Midway he had had a great carrier, the Lexington and then the Yorktown, sunk from under him. At a time when the Pacific carrier fleet numbered just four, three of which were assigned to Watchtower, he was fearful of further losses.

VADM Frank Jack Fletcher was the most battle-seasoned senior officer in Operation Watchtower. The experience of combat had taught him its costs. At both Coral Sea and Midway he had had a great carrier, the Lexington and then the Yorktown, sunk from under him. At a time when the Pacific carrier fleet numbered just four, three of which were assigned to Watchtower, he was fearful of further losses.

During the day, the Enterprise, Wasp, and Saratoga operated from a position about twenty-five miles south of the eastern end of Guadalcanal. From there, naval aircraft on patrol were but a quick few minutes from the beaches. Though Japanese planes from Rabaul six hundred miles away would have little capacity to strike them even if they could find them, the danger posed by the Japanese carriers (of uncertain location, Japan, Truk Rabul?) and submarines was considerable.

The critics ignore the possibility Fletcher might actually have learned something at Coral Sea and Midway, especially as he now found himself in the reverse role of his erstwhile opponents in supporting an amphibious thrust deep into enemy-controlled waters. Perhaps he really saw compelling reason to get the carriers clear of the invasion area and prepare for action. Just as he thought that with the marines ashore Turner’s immediate task neared its end, he understood the job of the carriers had only begun. In the short term they were the only shield against powerful naval and ground forces intent on destroying the marine lodgment. A large counter-landing would require strong carrier support to sweep away naval opposition before the actual landing force drew within range.

Fletcher envisioned another grim carrier battle soon. He must be ready for enemy carriers at any time, despite rosy intelligence estimates from Pearl—the most recent on the afternoon of 8 August—placing the Japanese carriers in home waters. Intelligence could be wrong, and the resulting surprise quite deadly, as the Japanese at Coral Sea and Midway could attest, not to mention Kimmel at Pearl Harbor. Hindsight has obliterated the validity of Fletcher’s prudence. The tactical necessity of protecting a fixed point put heavy demands on the defensive capabilities of Fletcher’s carriers. They were accustomed to strike swiftly and draw clear of retaliation. Now they were exposed not only to the threat of opposing carriers, but also subs (messages reported several en route) and the more vigorous than anticipated land-based air.

The sudden appearance of numerous medium bombers toting torpedoes, land-based air’s most effective antiship weapon, provided another strong reason for concern, especially given the combat air patrol’s questionable performance. Fletcher had not expected torpedo planes, certainly not ones augmented by fierce Zero escorts, could even reach him off distant Guadalcanal.

Twin-engine Mitsubishi G4M Navy Type 1 Attack Bomber, code named Betty by the Allies, launching a torpedo. It was built in greater numbers than any other Japanese bomber and it became the most famous Japanese bomber of World War II. The Betty would be a constant attacker during the Guadalcanal battles and specifically Henderson Field.

He queried Noyes whether the noon attackers “were actually carrying torpedoes,” and was assured they did. Maas wrote that night, “The use by Japs of long-range torpedo planes makes our present position untenable, dangerous, and foolhardy.” That was particularly true if the carriers could legitimately get clear without harming the overall mission.

The paramount question was whether the carriers were foremost in Fletcher’s mind, or the overall operation.

The bigger picture

Fletcher was said to be the only U.S. flag officer who understood that Watchtower would provoke the Japanese to a major naval counterattack. “His major job,” wrote author Richard B. Frank, “was to win the carrier fleet action that would decide the fate of the Marines.” If that was the case, it would have been reckless to risk his carriers before that threat actually appeared. He knew he would have to win that battle without ready reinforcement to make up his losses. No new carriers were due from the shipyards until late 1943.

There is little doubt Fletcher’s view of the situation off Guadalcanal took a serious accounting of the strategic significance of this scarcity of carrier power.

In January 1943 Rear Adm. George Murray independently confirmed Fletcher’s assessment. According to Murray, “The carrier task force problem, so far as refueling is concerned, hinges on destroyer consumption,” an “interesting sidelight [that] should be kept constantly in mind.” While “in an advanced area a task force cannot afford to approximate the low limit of fuel for the simple reason that it then is virtually immobilized for offensive operations involving 48 hours of high speed steaming.”

From 9 to 23 August, Japan only managed, using swift destroyers and stealth, to land one thousand lightly equipped infantrymen, whom Vandegrift’s dug-in marines outnumbered ten to one. A few destroyer-loads of infantry could not overrun the First Marine Division. That required artillery and other heavy weapons, plus many more men and supplies that only transports could bring. First, the Japanese must destroy or neutralize Fletcher’s carriers.

A severe defeat at that juncture would have cost Guadalcanal.

A well-situated referee to the controversy over Fletcher’s decision making was Marine colonel Melvin J. Maas. If his position on Fletcher’s staff makes his sympathy for his boss unsurprising, his status as a leatherneck inclined him to balanced perspective. He believed the only way the Japanese could retake Guadalcanal was through a major amphibious counteroffensive. Maas wrote:

“Marines cannot be dislodged by bombers. Because he saw the carriers as the key to preventing an enemy landing, he favored a withdrawal of the carriers, even at the expense of his brothers.

“To be able to intercept and defeat [Japanese troop landings], our carrier task forces must be fueled and away so as not to be trapped here.… By withdrawing to Nouméa or Tongatabu, we can be in a position to intercept and pull a second Midway on their carriers. If, however, we stay on here and then, getting very low on fuel, withdraw to meet our tankers, and if they should be torpedoed, our whole fleet would be caught helpless and would be cold meat for the Japs, with a resultant loss of our fleet, 2/3 of our carriers, and we would lose Tulagi as well, with all the Marines there and perhaps all the transports.

“It is true, Marines will take a pounding until their own air gets established (about ten days or so), but they can dig in, hole up, and wait. Extra losses are a localized operation. This is balanced against a potential National tragedy. Loss of our fleet or one or more of these carriers is a real, worldwide tragedy.”

Former marine staff officer and historian Herbert Christian Merillat, certainly no admirer of Fletcher, recognized in his postlanding strategy the “classic role of a ‘fleet in being.’” The U.S. carriers kept “their enemy counterpart at a cautious distance from the embattled island until one side or the other should find an occasion propitious for forcing the other into a ‘decisive battle.’” Although “few marines were aware of it,” Merillat thought, “they had reason to be grateful to the American carriers’ distant prowling.” Those flattops, “so long as they lasted,” provided “distant cover for the movement of supplies and reinforcements to Cactus.”

At that point in the Guadalcanal campaign, Fletcher’s ostensible “inaction” served the Allied cause far better than the alternative.

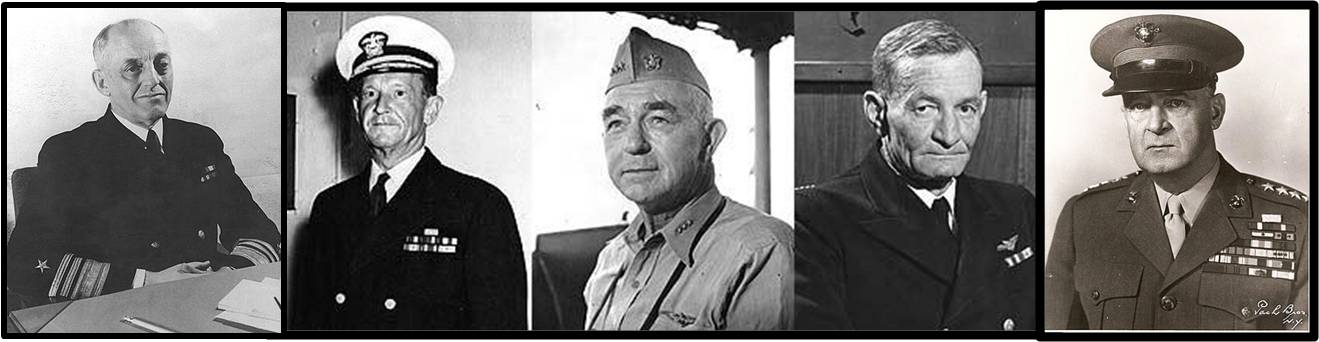

Leadership for the invasion of Guadalcanal: Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley – Commander, South Pacific Area; Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher – Commander Task Force 61; Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner – Commander, amphibious forces, Task Force 62; Rear Admiral John Sidney McCain – Commander, Aircraft, South Pacific; Maj. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift – 1st Marine Division

Next the Cactus Air Force