Testimony of Pilot #7

Aeroplane testing . . . demands for satisfactory results the highest training. It occupies no special place by virtue of this—it merely comes into line with the rest of engineering. Now, one can learn to fly in a month . . . but an engineer’s training requires years. It is evidently necessary, therefore, that engineers—men with scientific training and trained to observe accurately, to criticize fairly, to think logically—should become pilots, in order that the development of aeroplanes may proceed at the rate at which it must proceed if we are to hold that place in the air to which we lay claim—the highest.

CAPTAIN William S. Farren, British Royal Aircraft Factory, 1917

1) 1933, Trap in F9C Sparrowhawk testing the trapeze recovery system on the airship USS Macon; 2) jet testing; 3) book cover; 4) April 1943, first naval aviator to fly a jet – the Bell P-59A Airacomet at Muroc

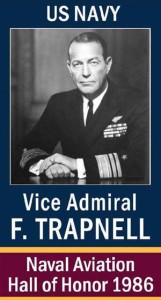

This second chapter takes its characterization as “harnessing the sky.” Below are excerpts from the book of that title telling the story of the test pilot who led naval aviation out of bi-planes to the airwings that won the war in the Pacific, and along the way became the US Navy’s first jet pilot, then founding the Navy Test Pilot School. With way too many critical stories for a complete picture of Trap, specific focus here is on his crucial role in the design and testing of the F4U Corsair of WWII and Korean War fame. TINS

Making the F4U Corsair a Combat Star

from

Harnessing the Sky:

Frederick “Trap” Trapnell, the U.S. Navy’s Aviation Pioneer, 1923-1952

by Frederic M. Trapnell Jr. and Dana Trapnell Tibbitts

Since when were Navy test pilots redesigning their aircraft?

Naval Air Station Anacostia, D.C., November 15, 1940

From his second-story office window, Lt. Cdr. Frederick “Trap” Trapnell, senior flight test officer for the U.S. Navy, surveyed the airfield, brooding. The Navy was being sucked into a war for which it was totally unprepared. American carriers harboring deck-loads of biplanes told the story: It would take years before the Navy could put fighters on its flight decks to match the Spitfires and Messerschmitts dueling over Great Britain. To make matters worse, planners now pegged September 1941—less than a year away—as the time by which U.S. military forces must be ready to go to war.

Sending young Americans out in obsolescent aircraft against the superbly equipped and battle-hardened Luftwaffe verged on criminal. Trapnell was resolute: It would not happen on his watch.

Parked outside on the apron was Vought’s XF4U-1 Corsair. Trap was to take it up this morning for an official speed test to demonstrate the prototype’s ability to achieve the magic four hundred miles per hour. While putting little stock in breaking speed records, he understood Rear Adm. John Towers’ ambition as chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics to set the world record with one of his Navy fighters. It would mean prestige for the service and perhaps additional funding from Congress.

As Trap stepped out of the hangar, the early morning light caught the sleek profile of the Corsair, glinting off the inverted gull wings and smooth, silver-skinned fuselage that wrapped the most powerful airplane engine anywhere in service. Indeed this was an elegant, racy machine. Airplanes that fly good usually look good, he told himself; too bad the reverse wasn’t true.

He zipped his flight suit against the crisp bite of the winter morning and strode out to begin his preflight check. Walking around the machine, he noted the temporary changes made in preparation for today’s speed run. The radio mast and antenna had been removed, and the hand-holds at the wingtips and gun ports in the leading edge of the wing were covered with tape, all to minimize drag.

… In September 1939, the president proclaimed the existence of a limited national emergency based on the escalating aggression of Nazi forces in Europe, and he directed measures for strengthening national defenses within the limits of peacetime authorizations.

… by mid-1940, with the storm clouds gathering across the Atlantic and the Japanese stirring unrest in East Asia, the U.S. Navy found itself saddled with inadequate fighter planes and no ready prospects for real improvement. … With the obsolescent Brewster Buffalo in limited operation, the Grumman Wildcat not yet operational, and far superior aircraft clashing in the skies over Europe and Britain, the U.S. Navy found itself in very deep water indeed.

… Even into early 1941, carrier squadrons continued to operate with biplane dive bombers and fighters;

… The next generation of Navy fighters would be bigger, heavier, and more complex than any airplane in the service pipeline for the foreseeable future. In light of this daunting array of requirements, the Navy’s current lineup of fighter prototypes—the Airabonita, Skyrocket, and Corsair—did not look all that promising. Worse, the standard procedures for testing and modifying to render any of these aircraft serviceable could well take three to four years.

As he clambered down from the cockpit, a colleague ran from the hangar to tell him the news: Final numbers on his speed test were in. He had done it, 402 miles per hour! This made the Corsair the fastest fighter in the world, a record for the Navy and for the nation. And Rear Admiral Towers sent his congratulations. Trap smiled and then headed back to his office, troubled by broader considerations.

The performance of the Vought XF4U-1 Corsair pushed it to the top of the Navy’s list of not-very-promising prototypes. Trap’s speed runs in the airplane prompted the Navy to issue a rare press release. The resulting Washington Daily News article of December 20, 1940, described Trap’s flight of “400 odd m-p-h” in an airplane “known technically as the F-4-U, officially the ‘fastest airplane in the United States today.’

Indeed the XF4U-1 Corsair demonstrated many of the flight characteristics the Navy wanted most: speed, rate of climb, high altitude performance, stability throughout its speed range, and a rugged airframe.

Nevertheless, the design had serious flaws that rendered it unacceptable.

Trap later summed up the Corsair’s main challenges this way. “The F4U showed very superior performance, but no aileron control, a vicious stall, and terrible vision.”

(1) The preliminary flight test report highlighted the difficulty of rolling the airplane, poor pilot visibility from the cockpit, and a sudden power-on stall. As a Corsair slowed to stalling speed in landing configuration, the left wing stalled first, dropping abruptly without warning and throwing the airplane into a spin that would spell disaster if it occurred on landing approach.

(2) In addition, the roll control was highly nonlinear in the left-to-right direction, resulting in what Trap’s flight test report describes as a “kick” when the control stick was deflected sharply.

(3) Another disturbing finding was poor visibility from the cockpit, which was “restricted by the large fuselage and wing root cord and hampered by the window arrangement.” And visibility was further impaired by the low position of the pilot under the shallow canopy.

(4) These early problems were only precursors to issues that surfaced as Navy testing progressed. Perhaps the worst of these was that the airplane could not be made to roll fast enough, especially at high speed.

(5) Another deficiency was made irrefutably evident in the Battle of Britain: to be effective, fighters had to deliver a knockout punch in a single short burst of gunfire.18 The prototype Corsair had one .30-caliber and one .50-caliber machine gun mounted in the upper engine cowling and one .50-caliber gun in each wing, far less than European fighters.

(6) Finally, insufficient fuel capacity had serious implications. The Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engine was demonstrating higher fuel consumption than anyone had expected, … nearly three times the Wildcat burn rate! In addition, it was becoming clear that the Navy needed fighters with more range than previously thought. This meant that the 273-gallon fuel capacity of the Corsair was not nearly enough. The airplane simply could not range far enough from its carrier to meet the Navy’s needs.

Trap wrote of this period: “I was Flight Test Officer during the era . . . and deeply concerned with the three new prototypes the Navy was evaluating” … In a rather desperate gamble,” he wrote, “we chose [the Corsair] in the expectation of correcting its defects.” Doubtless they felt this airplane was their best bet because of its intrinsic performance. Now the question before them: How to fix it?

REINVENTING THE CORSAIR

In early 1941, with the United States projected to be at war within the year, the pressure to get a new fighter into the fleet was palpable. The BuAer team evaluated further test results of the Corsair in light of the combat environment they now faced. In so many ways they liked this airplane, but it remained saddled with problems for which there was no simple fix: … The team agreed: no matter how long and how difficult it proved, these problems would have to be solved. Vought was not going to like their verdict. A few days later, the BuAer team sat down with Vought engineering executives to present their critique, with Trap leading the discussion for the Navy… The meeting ground to its grim conclusion when Trap rendered the team’s final verdict: either Vought would fix these problems or the Navy would be forced to scrap the Corsair and struggle along with the Wildcat.

… The next day, Trap called together some of his pilots and a few engineers. … He laid out a blueprint of the Corsair on the conference room table to illustrate his ideas. Determined to salvage this fighter even if it meant radical modification and major surgery to the original design, they set to work on a series of major alterations to correct the airplane’s troubles.

Step one, move the fuel carried in wing tanks into the fuselage instead. To do this, the cockpit had to be moved aft, say thirty inches, to make room for a big fuel cell in the fuselage in front of the pilot, directly over the wing, where fuel state would not significantly affect the center of gravity and longitudinal trim.

Since this cockpit location would impair the already questionable visibility over the nose, the pilot position should be raised six to eight inches, which would provide even better visibility than the current prototype afforded. Trap suggested a blown bubble canopy like that of the Spitfire, which would provide better headroom for the pilot and improved rearward visibility.

Finally, to improve the roll rate, Trap wanted longer-span ailerons and shorter-length flaps. The proposition seemed logical, but Vought was going to balk at such drastic changes. There was general agreement: these alterations were a neat solution to the problem, but the Vought people had better be sitting down when they heard this.

At the subsequent meeting with Vought brass, Trap explained the proposal, laying out his sketches and talking them through the changes. The Vought people listened in stunned silence. When he finished, they were visibly chagrined. This was a complete redo.

Since when were Navy test pilots redesigning their aircraft?

[RS aside: Trap finally flew the Grumman XF5F-1 Skyrocket in March 1941, … Skyrocket was not going to cut it. Back on the ground, he once again spoke privately with Roy Grumman to spell out the airplane’s shortcomings. …

Trap looked his friend coolly in the eye and told him that if Grumman didn’t stop fooling around with this twin-engine dodo bird and put their engineering talent to work on a decent single-engine fighter using one of the new big engines, the Navy would not buy any more of their fighters. Furthermore, he added, BuAer had decided to proceed with the Corsair rather than the Skyrocket.

Roy (Grumman) allowed that his people had already started on a new single-engine fighter design that he thought would interest Trap. The prototype could be ready for testing as early as mid-1942. Trap appreciated Roy’s accommodation but remained apprehensive. Mid-1942 might be too late.]

The result would be the F6F Hellcat. Trap would play a major part in getting the Hellcat to the fleet but that’s another story.

This redesign removed the fundamental stumbling block for the Corsair. Many years later, Adm. Charles D. Griffin commented in his oral history on the impact that Trap and Flight Test had had on the Corsair and other designs: “We redesigned some aircraft to a large degree right there at Anacostia. Of course, Trapnell was the expert in this. . . . No [we did not merely test airplanes], we actually redesigned some of them right there. . . . This ability on the part of the test pilots was greatly sought after and much appreciated by the contractors, by the design engineers, and so forth.”

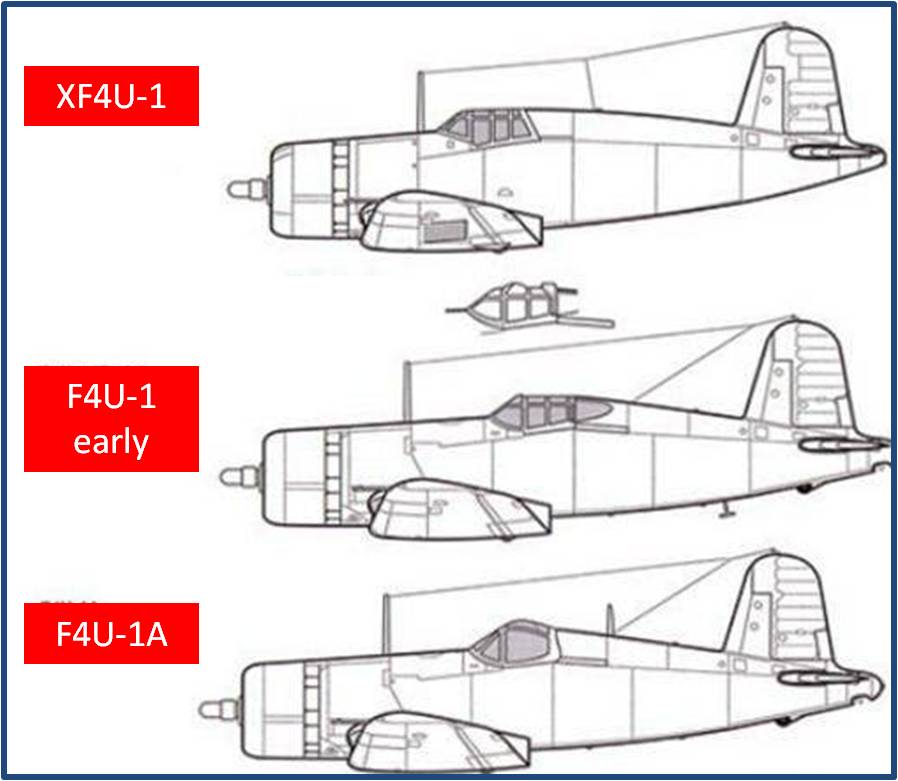

XF4U-1 and the combat F4U Corsair

The airplane’s sluggish roll remained a liability, and Vought had yet to correct the problem. Indeed, the flaw highlighted two closely related problems. First, improving the rate of roll required bigger, more effective ailerons. Second, heavy stick loads meant the pilot still had to use all his strength to make the airplane roll at any reasonable rate….

And so in the spring and summer of 1941, Vought engineers and test pilots resignedly undertook a crash program to lighten the control forces of the prototype ailerons, trying various control linkage arrangements…

Trap also took the prototype up periodically for check flights to monitor progress and was pleased by the diligence with which Vought pursued the goals he had set.

Later in the war, the Corsair’s maneuvering performance would receive the highest praise from fighter pilots who had their lives on the line. Its fast rate of roll, especially at extremely high speeds, was to become legendary.

The first Corsair off the production line flew in June 1942…. By early 1943, the Navy would finally have an alternative fighter (Grumman F6F Hellcat) that was more stable and pilot-friendly, so the Corsair did not deploy on carriers until 1944, after its two major flaws had been corrected. Until then, it went into land-based Marine and Navy squadrons, operating in the Solomon Island campaign starting in February 1943. While not easy to land on board ship, its troubles caused little difficulty in land-based operation, and the airplane proved to be exactly the fighter these island-based flyers wanted….

In mid-1944, the Corsair was integrated into both Navy and Marine shipboard squadrons, and their pilots came to love the airplane, which became one of the outstanding fighter planes of World War II, achieving an eleven-to-one kill ratio.

The U-Bird, or as the Japanese called it Whistling Death, remained in production through successive model changes for eleven years and four wars, the longest production run of any U.S. fighter. And its remarkable rate of roll at any speed, the quickest of any contemporary American fighter, was one of the many characteristics praised by the pilots who flew it.

Trap had been a commander for a little less than a year when he was promoted to captain in May 1943; at the same time, he received orders transferring him out of Flight Test to a new post on the West Coast. He had guided the Flight Test Section through a highly stressful period, meeting the charge to outfit the U.S. Navy for air war. The airplanes they had tested, evaluated, redesigned, refined, and approved went on to win every key air battle in the Pacific. The challenge had been both exhilarating and treacherous; two of his pilots had been killed in the line of flight test duty.

(including flying the recovered and repaired Japanese Zero and evaluating it against both the Wildcat and Corsair and then developing the lessons for combat aviators)

It was now Trap’s turn to go to war.

Adm. Charles D. Griffin, Trap’s good friend and number two at Anacostia, spoke of this time and place in his oral history:

The Flight Test officer was Fred Trapnell, who in my opinion was probably the greatest test pilot the world ever saw. He was absolutely terrific. He had no advanced degrees, largely through choice, but he could take an aircraft up, find out what was wrong with it, bring it back down, and not only tell the engineers what was wrong with it but the most probable way for them to proceed to cure the problem. He was absolutely brilliant in his field and was recognized as such I think by the entire aviation industry. I was his number two and felt it was really an honor and a pleasure to work with him.

As chief of Flight Test for the Navy, Trap led Navy Flight Test into early testing of prototypes to shorten test-and-development cycles, thereby reducing the time from conception to deployment of new airplanes. Furthermore, he had pursued getting better fighter planes with diligence and determination, putting on a fast track the development and delivery of not one but two superb fighter types for the operational Navy: the Corsair and the Hellcat, shipboard fighters that would have been prized in the inventory of any air force in the world.

These airplanes swept Japanese aviation out of the skies, saving the United States immeasurable blood and treasure while accelerating the victorious conclusion of World War II. Trap’s achievement—though not made in combat conditions for which so many of his colleagues received decorations—stands among the most important contributions made by an officer of his rank to the American war effort.

(After several commands) At the request of Rear Adm. Arthur Radford, who would later become commander in chief of the United States Pacific Command and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Trap left command of the carrier Breton …to join the battle fleet itself as Radford’s Chief of Staff … Task Force 38 was the operating name for the U.S. Navy’s battle fleet and main strike force in the Western Pacific.

(In late Dec. 1944 the influx of new carriers brought Marine Corsair squadrons on board the CV’s.)

They amply and decisively demonstrated what the Marines had long asserted: the Corsair had come into its own as a superb carrier fighter. “Any kid who can ride a tricycle can learn to fly a Hellcat,” the Marines said. “Flying a Corsair is a bit more challenging, which was not a problem for Marines. And a Corsair could wax a Hellcat any time at any altitude.” On hearing this, Trap chuckled contentedly in the quiet satisfaction of seeing the aircraft lineup he and his Anacostia team had so rigorously tested, struggled with, torn apart, and put back together—the Corsair, Hellcat, Dauntless, and Avenger—all performing so well under fire in the fleet.

asserted: the Corsair had come into its own as a superb carrier fighter. “Any kid who can ride a tricycle can learn to fly a Hellcat,” the Marines said. “Flying a Corsair is a bit more challenging, which was not a problem for Marines. And a Corsair could wax a Hellcat any time at any altitude.” On hearing this, Trap chuckled contentedly in the quiet satisfaction of seeing the aircraft lineup he and his Anacostia team had so rigorously tested, struggled with, torn apart, and put back together—the Corsair, Hellcat, Dauntless, and Avenger—all performing so well under fire in the fleet.

*************************

One has only to look at the pictures above of that first XF4U-1 compared to the combat version to note the marked differences. While its early problems with carrier landings allowed it to be eclipsed as the dominant carrier-based fighter by the Grumman F6F Hellcat (5160 air-air kills), it was a perfect aircraft for the Marines. Eventually getting on carriers in 1944, Corsair pilots shot down 2140 Japanese planes with an 11-1 kill ratio. It served with distinction for Close Air Support in the Korean War. Eventually, more than 12,500 F4Us would be built, comprising 16 separate variants. Its 1942–53 production run was the longest of any U.S. piston-engined fighter .

Hunters, Sunlit Corsair, Dusk Patrol by Peter Chilelli

Hunters, Sunlit Corsair, Dusk Patrol by Peter Chilelli

**************************

Trapnell Field – the airfield at Naval Air

Station Patuxent River, home of the

Navy Test Pilot School that Trap founded.

Frederick Trapnell Jr. had always resisted writing a biography of his father, who left little material on which to base his life’s story. As a result, the legacy of Frederick “Trap” Trapnell as one of the U.S. Navy’s pioneering aviators and its foremost test pilot had been preserved only in the archives and memories of those who served beside him, but not in print.

Frederick Trapnell Jr. had always resisted writing a biography of his father, who left little material on which to base his life’s story. As a result, the legacy of Frederick “Trap” Trapnell as one of the U.S. Navy’s pioneering aviators and its foremost test pilot had been preserved only in the archives and memories of those who served beside him, but not in print.

And yet, Fritz and his daughter, Dana Tibbitts, knew it was a story worth telling. It just took a little prodding from friends who knew something of Trap’s story and “browbeat me into thinking this was important,” said Fritz, who alongside Trap’s granddaughter Dana began researching and writing the book in 2010—a process that culminated with the publishing by Naval Institute Press of Harnessing the Sky: Frederick ‘Trap’ Trapnell, the U.S. Navy’s Aviation Pioneer, 1923-1952.

A must-read for aviation and World War II buffs alike, the book spends a couple brief chapters reviewing both Naval Aviation’s infancy and Trapnell’s early years as a New Jersey youth before diving headlong into his career shepherding the service through one aviation advancement after another. In many ways, in telling Trapnell’s story, his son and granddaughter have also written a history of Naval Aviation.