(Note: This piece was originally published on the Project White Horse Forum for Veterans Day 2010.)

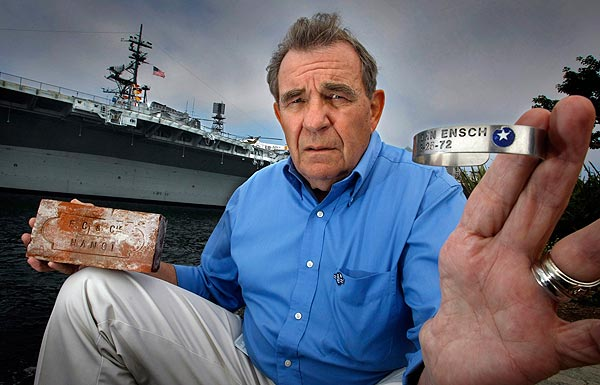

In high school, Joleta McNelis was never far away from a man she had never met. She carried Lt. John “Jack” Ensch in her heart — and on her wrist. Aside from his name, the only thing McNelis knew about Ensch was the date his fighter jet was shot down over North Vietnam: 8-25-72. It was etched under his name on the metal bracelet she bought when she was 14.

Three months earlier, on the day Jack Ensch and Mugs McKeown became double “MIG killers” – the 23rd of May 1972 – I logged my 25th combat mission as one of the strike aircraft they, with flight school buddy wingman Rookie Rabb in their F-4 Phantoms, were protecting. Ensch’s squadron,VF-161, were readyroom next door neighbors to my A-7 squadron , VA-56 Champs. Mugs would move on shortly to be commanding officer of TOPGUN and Jack would become a POW that August.

When Ensch arrived there (Hanoi Hilton) in August 1972, he brought news that he passed along to his fellow prisoners through tap codes between cells: People across America were wearing bracelets with their names on them. “They were dumbfounded,” Ensch said.

USS Midway and Carrier Airwing Five had sailed from Alameda California on the 10th of April 1972, two months earlier than planned, missing crucial aspects of our training and in record time – seven weeks – we were off the coast of Vietnam, beginning combat missions on 29 April and going “up North” with the SAMs and MIGs within ten days. That May for Midway was very instructive for a lot of young men wearing “wings of gold” in combat for the first time. Our first missions seemed like something out of WWII and French battlefields. We weren’t bombing illusive Viet Cong targets in a jungle, rather we were fighting massed troops with tanks centered around the town of An Loc. Known as the Easter Offensive, North Vietnam’s General Giap had mounted a major conventional war type offensive into South Vietnam. As operations re-focused on putting pressure on North Vietnam, we flew mining missions to Haiphong Harbor, and other coastal waterways. Flying cover for those strikes, Ensch’s Phantom squadron shot down a covey of MIGs. I flew my first “Alpha Strike”(30 or so plane major strike) to a little place called the Than Hoa Bridge. We saw everything but the kitchen sink coming flying up that day. Indeed my great bud Floo and I had a SAM go right between us, so close you could read the Russian markings – fortunately for us they did not turn out to be either the “writing on the wall” or the harbinger of names on a bracelet.

By the time Midway aircrews flew those missions in 1972, most of us were under no illusions about how the country felt about the war and indeed sometimes about us – the Yankee air pirate “war criminals.” The air war, particularly over North Vietnam had long been a pawn in Secretary of Defense Robert Strange McNamara’s flawed strategy of war. The “stick and carrot” ploy having failed, President Nixon pulled off the gloves that Spring and sent Air Force and Navy pilots back “down town” – Route Pack Six, Hanoi, Haiphong, Thud Ridge, the Red River Valley.

No one has deemed us the “greatest generation,” but we didn’t much care then or now. We were proud to be American fighting men, we loved our country as much as any from any time since the Revolutionary War, we were well trained, really loved being Naval Aviators and that special aspect flying off of carriers, and despite all too real and rationale fear, relished the challenge – as Right Stuff author Tom Wolfe described – of “jousting with SAM and Charlie.” Most of all, we simply liked being around the kind of people who chose to do that kind of stuff. And truth be known, we knew we were fighting not to win a war but to gain position strong enough for Nixon and Kissinger to negotiate the U.S. out of Vietnam. That meant bringing home those “kind of people we liked being around” who currently enjoyed the hospitality of North Vietnam residing in the Hanoi Hilton, our POWs.

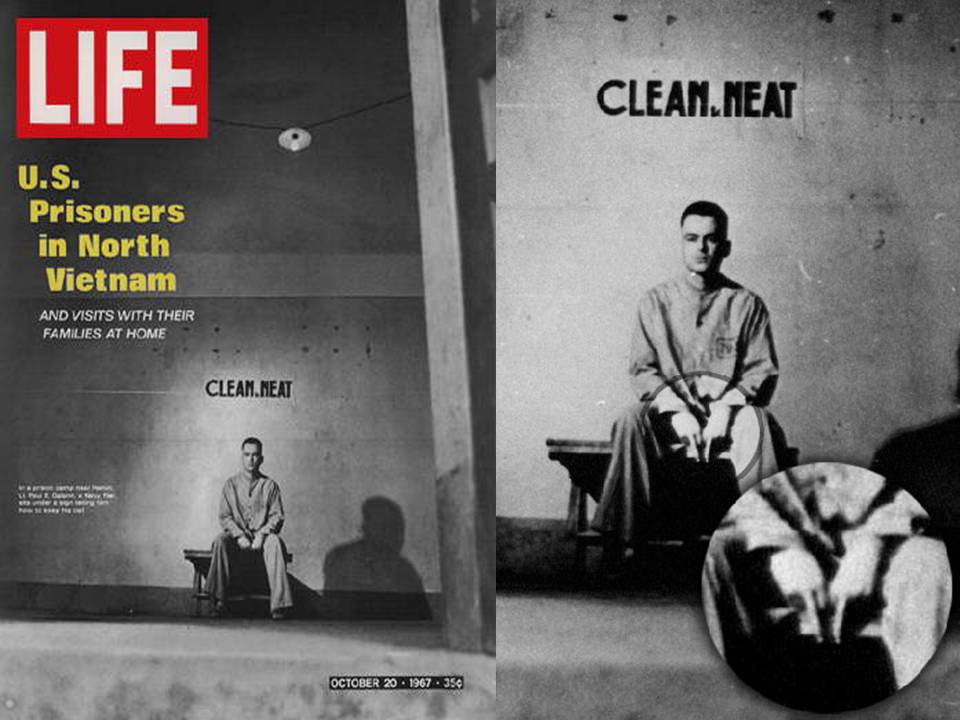

One of those POWs, Paul Galanti (the Life Magazine “birdman”), shot down in an A-4 Skyhawk on 17 June 1966, was best friend of my squadron commanding officer Lew Chatham.

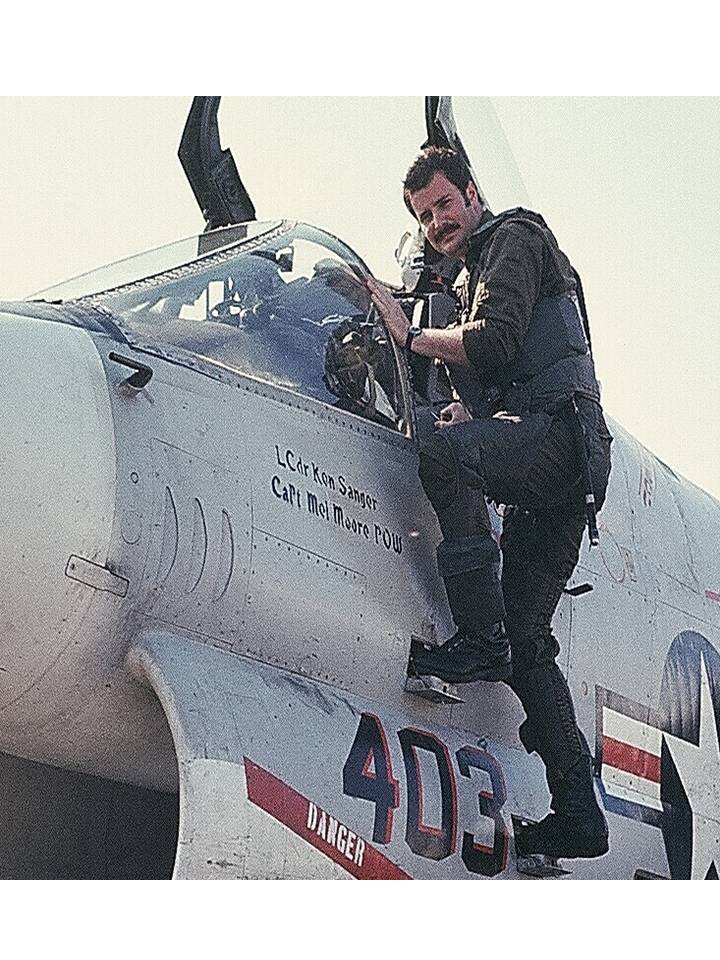

In a time honored tradition for fighter aircraft, the Skipper’s name was painted on the side of the cockpit of NF 401, as was each pilot’s name down the pecking order on squadron aircraft. Chatham had Paul’s name painted under his own. Indeed, a POW name was stenciled on all Champ aircraft under each of our names. The picture below is of me manning up in our operations officer’s aircraft NF 403 showing Navy POW Capt Mel  Moore’s name. Moore was an A-4 pilot and Executive Officer of VA-192, shot down on 11 March 1967 while flying a surface to air missile suppression or Ironhand mission. As far as I know, the VA-56 Champs were the only Navy or Air Force squadron to place POW names on their aircraft. We knew for what and for whom we were fighting.

Moore’s name. Moore was an A-4 pilot and Executive Officer of VA-192, shot down on 11 March 1967 while flying a surface to air missile suppression or Ironhand mission. As far as I know, the VA-56 Champs were the only Navy or Air Force squadron to place POW names on their aircraft. We knew for what and for whom we were fighting.

The vietnam War was an extremely devisive period for America. But as Jack Anton wrote in the Los Angeles Times on November 4th, “The plight of the POWs gave people a way to separate their feelings toward policymakers from their feelings toward those who fought in the war — a shift in public attitude still evident today. Whatever people think of U.S. policy on Iraq and Afghanistan, support for the troops remains strong. So, too, do the connections made by Vietnam-era bracelet wearers. … More than 5 million POW/MIA bracelets were sold for $2.50 to $3 apiece in the early 1970s. … Thirty-seven years after the wars end, the Defense Department‘s Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office receives requests for information on former POWs or relatives of missing servicemen nearly every day.”

This post was originally intended to be a short link to Anton’s article, which being in the La Times, many of you would not see. “Vietnam war bracelets come full circle,” on the front page of all things, caught me by surprise. It intertwines the story of how the bracelets came to be with stories of POWs like Jack Ensch and the people who wore their bracelets, some as teenagers. Ensch said he is still struck by the outpouring of goodwill. “Even those people who were against the Vietnam War could identify with us being held captive there — the torture and the mistreatment. Nobody could argue that wasn’t wrong,” he said. “I think it was a collective learning experience for our society.” Anton’s article is well worth your time to read and I offer my thanks to him for writing it.

If the Vietnam War had one good aspect, it was that our citizens relearned that what you think of war or a particular war should not reflect on what you think and how you treat the warfighter. No one cheered service men coming through airports in those days – they do now. No one lined the streets for miles for a soldier’s funeral, or placed American Flags along the route then – they do now. Something that was not right, now is. Once again we honor our veterans – all of them.

Similar to what I noted several years ago in the Ghosts of Christmas Past;Memories of Fly Navy, Anton’s bracelet story generated one of those flashback/reflection moments and caused me to recall a comment by my golfing partner and retired Navy Phantom puke John “Dancing Bear” Evans. He reflected one day that with no disrespect meant to the “greatest generation,” the WWII guys went off to war, did their business of warfare and did it exceptionally well, but with a country strongly behind them. The Vietnam warriors were no less brave, also did their country’s biding, but did it not only in the hostile combat environment but returned to a hostile environment at home. They indeed deserve recognition as a very great generation.

As we honor all our veterans, I suggest to you a separate moment of thought for those who indeed stood alone. I for one am proud to have shared the St Crispin’s Day Agincourt “band of brothers” moment with you.

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,From this day to the ending of the world,But we in it shall be remembered-We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;For he to-day that sheds his blood with meShall be my brother

So on this Veterans Day 2010, here’s a cold one to the Vietnam War band of brothers!

Project White Horse 084640 and Boris send.