Testimony of Pilot #9

the greatest pilot I ever saw.- Chuck Yeager

Hoover’s “the finest acrobatic pilot we’ve seen in our lifetime” -Astronaut Wally Schirra

greatest stick-and-rudder man who ever lived – Jimmy Doolittle

Diversity of experience over their careers is certainly a characteristic of the aviators featured in this second offering of “harnessing the sky” stories within the testimony series. Bob Hoover taught himself aerobatics as a teenager, as a fighter pilot shot down a FW-190, served as a prisoner of war with aviators from various countries/services, escaped and stole a German fighter, as an Air Corps test pilot, among other missions was back-up pilot and chase for Chuck Yeager’s supersonic run in the Bell X-1, developed bombing techniques for the F-86, taught them in Korea while flying combat missions as a civilian, went to US Navy Test Pilot School, carrier qualified and did multiple carrier oriented tests, tested the F-100, and by demonstration convinced the Air Force it was the right plane for the Thunderbirds. Then he got famous. His airshow performances in the P-51 and Shrike Commander made him a household name.

If aviators like Yeager. Schirra and Doolittle consider him the “best” then his testimony just might have some value. TINS

Cockpit to Cocktail Party: The Bob Hoover Story

From

Interview with Bob Hoover (2002)

By Kathleen Bangs (re-posted with her permission)

It was a lucky break. In 2002, across the wide expanse of a Florida trade show conference hall, I recognized an unmistakable aviation icon. A lanky figure, under his signature Panama hat, moving as a swarm of fans buzzed around him. It was Bob Hoover.

A second lucky break, I just happened to have a tape recorder with me. Hoover graciously agreed to sit down for a spontaneous interview, with no particular plan for his recollections, other than to save them for posterity. We lost Hoover in 2016. In celebration of his extraordinary life and contribution to flying, I hope fans both old and new will enjoy reading this never-released interview.

You’ve been able to do almost unnatural things in airplanes, maneuvers that seem to defy the laws of physics. When you look at your talent, whether it’s God-given or training or whatever it is, where do you think it comes from? What sets you apart from everybody else?

BH: Sheer luck.

I knew you’d say that, but if you had to analyze it. What has given you not only ability, but longevity?

BH: I’ve thought about things. The “what ifs.” I think ahead about what if this goes wrong, what if that goes wrong. I’ve already thought it out, so I know what to do. And I could tell you stories by the hour of situations I’ve walked away from, yet didn’t have to think in the moment about what to do, because I just did what I’d already thought of.

Take the greats like yourself, or Duane Cole, or Art Scholl for instance, another great pilot. Would you say it’s inborn, or can it be learned? Can you take someone up one time and determine if they’re going to be able to ever cut it as an airshow pilot?

BH: Art Scholl was the worst I’d ever seen when he first got into aerobatic flying! He was on the U.S. Aerobatic Team and I was team captain. And before we went over to Moscow, Russia, for the world championships I remember thinking this is ridiculous having him on this team. He’s no more qualified than the man on the moon!

Charlie Hilliard worked out with him for about a month or so. And he dressed him up to the point that he was fairly decent when we got to Russia.

In the aviation of today, who or what do you think is being overlooked or forgotten?

BH: Right now, I can go to an Air Force base, and if someone mentions General Jimmy Doolittle, you can see there are young officers wondering, “Who the heck is that?”

What would you want young people to know about aviation through Bob Hoover’s eyes?

BH: That’s a tough question. I’ve expressed this very few times in my life. I think it’s the way some young people are trying to “find” themselves today. I get so sick of some young fellow 35 years of age, who’s still trying to find himself. I’ve got a driver, because I like to be able to have a drink, and not drink and drive. I always hire a driver. And this fellow is a delightful person, and he’s a bit older, but I can’t motivate him.

But you can’t motivate somebody else. That has to come from within the person, in wanting to achieve, to be successful, in whatever it is. People ask, “Bob, can’t you give me some hints?” and I say get the best education you can, then go in the military and you’ll get the best flying in all the world. And they’ll say, “Well, I can’t pass a physical for that.” I say well alright, then you go get your master’s and a Ph.D. And don’t get it in history. Get it some field that will give you an opportunity to get ahead in life, and then you can make so much money you can buy whatever airplane you want to fly.

I really feel it’s a pity that people can’t find themselves. Hell, I knew where I wanted to go the day I was 16 years of age, and I never lost sight of it. I just kept the blinders on.

I was lucky at 16 to start flying, and it also provided a vector for my life. But if not for my first flight instructor, Lt. Colonel Robert McDaniel, I would have never gone back for a second lesson. Who was the most particular influential flight instructor for you?

BH: I’m a rarity. Nobody could teach me. I got sick every time I got in an airplane because of airsickness, so I kept at it until I could get over it. I was sick, swallowing it over and over, but was so motivated I would not let that stop me. I was determined in my mindset. And I conquered unusual attitudes, one step at a time, until I could handle that without becoming ill.

There was no one I could get aerobatic instruction from, no one knew anything about aerobatics in my town (Nashville, Tennessee). So, I tried things myself. I’d think, I wonder if I could do this, I wonder if I could try that, and then incrementally kept stretching it to not get sick. Even to this day, if you were to ask me to go out and ride with you, offer you some suggestions, and I’m sitting in the back…watch out!

Pilots must always be asking you for flying tips.

BH: I’ve told a lot of people how to do certain things, only to have it come back in my face because he goes out and kills himself. He doesn’t do the things I told him when he asked the questions. The earth’s awful solid and it’s going to be solid forever. So, if you want to do something, you do it up high. And then you learn it, and do it so well, you know you’re safe when you come down low.

In your iconic Shrike Commander airshow performances, how did you keep the G loading low during the routines?

BH: The Shrike had a 4.3 positive G load limit. When Rockwell asked me to fly the Shrike, I thought if I could get my routine down to 2.5 G, I could still hit a gust load and keep it under 4 G, and get this plane the recognition it deserves.

The rule of thumbs, is if you have less weight you can pull a little more G without damaging the structure. The first time I went out to play with it, I did 3.5 G. Then I started working and got it down to 3 G for the first show. We started selling airplanes just like that. We had maybe 100 on the ground, and were building one a month. We sold them all within probably five months of my first demonstration. We had a three-year backlog of orders! And, we kept raising the price, without having to change a thing. The company went from a $13 million a year loss to a very profitable situation.

Were there problems with regular owner-pilots wanting to go up and impress their buddies by pretending they were Bob Hoover?

BH: The biggest fear of my life. And it happened, and they’re not with us anymore. That’s very unfortunate. There’s no way you can keep people from sticking their nose into something they don’t understand. People called me from all over the world asking if I’d tell them what airspeed I enter such-and-such a maneuver at, and I’d say “I’m very sorry, it’s just something you’ll have to figure out for yourself.”

One time I did it—shared every bit of information I had with a fellow—about P–40s. Then I watched him kill himself in one. And I decided I would never do that again.

Do you think when pilots try to mimic you the reason they crash is that they exceed the design limits of the airplane, or because they mess up the maneuver and hit the ground?

BH: Leo Loudenslager (seven-time U.S. aerobatic champion, died in a 1997 motorcycle crash). Leo was as fine a pilot as I’ve ever known. He had a narrator that would dedicate his flight performances to me. Leo came to Reno one year, a teenager really. We talked. I helped motivate him—I advised him to get his ratings first—and he went on and became a world champion. He also asked for advice, even when he was at the top. He solicited my input, asking, “If you have any criticism, I’m open to it, I want to know.”

So, I said, “Leo, I don’t like your routine. The reason being you don’t have a large enough margin for safety. One hiccup, you’re going to hit the ground. And those fans out there you’re doing it for? They’ll forget about you tomorrow. They don’t know how close you’re coming to killing yourself, but I do. Are you here to have fun and entertain people, or kill yourself?”

How do you manage a healthy respect for the ground, or let’s just call it what it is, fear. Do you think the mismanagement of fear causes good pilots to crash?

BH: Absolutely. It’s the reason I’m alive today. I’m just like anybody else. I get scared when I know all hell is breaking loose around me, or I’m on fire, but I have conditioned myself to react with “What are you going to do to get out of this?” That has saved my life a lot of times because I could respond without having to think.

So, you never allow yourself to become a passenger to your own fear?

BH: I keep that glide speed until it stops. I’m on the controls. I don’t give up.

Hoover’s famous advice: “Always fly it as far into the crash as you can.”

What first got you interested in flying?

BH: My family and other people talking about Charles Lindbergh’s accomplishments. That tweaked my interest because it was such a big thing in history. I built model airplanes and would run outside if I heard an airplane flying over because you didn’t hear very many back then.

When did you meet Lindbergh?

There was a project for an airplane that could fly even further than the SR–71. It was the XB–70 Valkyrie. Lindbergh visualized a supersonic transport. Size-wise, the Valkyrie was being designed as a heavy bomber, but we figured out you could put in 35 first class seats. In talking with Lindbergh, we said it wouldn’t be practical. And we were correct. Boeing wanted to build it initially, and North American bid on it because we were going to build some parts of the structure for Boeing. But Lindbergh was so fascinated by those things.

Did you ever personally get to know the notoriously reclusive Charles Lindbergh?

BH: We became very good friends. He’d come out to visit me under an assumed name. He kept up to date on things. I’d take him to my home, but he didn’t drink. You’d never know it, because he’d sit there at the bar with me and you’d never know he wasn’t having as much fun as you were. Lindbergh was very shy, very introverted. He didn’t want to be known.

I helped bring him back out of obscurity with the help of astronaut Wally Schirra and others, who helped convince him. We wanted to give him an honorary award. I was the president of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots. It’s a very prestigious organization with members like Neil Armstrong. I got Chuck Yeager into it when he wasn’t qualified. Got him into an experimental airplane so that he would be qualified, as he’d not joined beforehand, and the rule was you couldn’t get in if you weren’t flying something experimental.

Lindbergh told me he wanted to accept the award, but said he wouldn’t allow any photographs, and wouldn’t sign any autographs. He wanted to be taken into the ceremony the back way, with security, because he didn’t want to be bothered with people wanting to talk with him. By this time, we were on a first-name basis and he wanted me to call him Slim, which I did until his later years.

I said, “Slim, no one’s going to recognize you because when the Apollo 11 crew comes back from the moon, they’re going to be given an award on the same stage that I want you to receive your award. Nobody will recognize you anywhere, anytime. When I’m sitting with you now, nobody knows who you are.” I’d bring him into the North American company and nobody knew who he was!

So, Wally Schirra was on my board. He wrote Lindbergh a terrible letter! He said, “Bob has offered you the opportunity of a lifetime. Here’s an opportunity for you to be honored by people who have all risked their life in being a test pilot. This is your last opportunity, you’ll never get another chance. And I should think this is one thing that would be important to you.”

Then, Lindbergh called and asked if I could promise him there would be no photos. I said “I can’t promise you that, but I’ll try to protect you as much as I can.” He said, “Okay, but can you get me in the back door so I won’t have to talk to anybody?” I said, “Slim, you could waltz in through the front door of that Beverly Hills Hilton Hotel and nobody will know who you are! Everybody’s looking for the astronauts!”

Charles Lindbergh and Neil Armstrong are shown at the 13th Annual Awards Banquet of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots. In the center is Mrs. Robert Hoover. Photo taken in Beverly Hills , Calif. on September 28, 1969.

I told him: Walk through the front door and I’ll be standing there waiting for you. And I had in my suite Bob Hope, Conrad Hilton and his son Baron, the Apollo 11 crew, and a whole bunch of movie people—the big names!

Quite the cocktail party!

BH: But Lindbergh didn’t want to go in there. He wanted to have me listen to him give his speech. So, I took him into the bedroom which was right off the suite—I had the presidential suite—where all the people were gathered, having cocktails.

What did you think of his speech?

BH: It was the most boring thing I ever heard in my life! When he finished, all I said was, “Boy that was just great, they’re going to love it!” Hell, nobody cared what he said. It was the fact that he, Lindbergh, was there.

How did it go?

BH: Well, he let me take him in to meet the people I just mentioned. Bob Hope had his own personal photographer who tried to take a picture but I ran over and jumped in front of him.

Do you think his behavior was a reaction not so much to his aviator fame, but instead to his terrible personal tragedy?

BH: Oh, it was the kidnapping yes. He told me that’s what the problem was. The last letter I ever got from Lindbergh was him writing to thank me. He wrote, “I think I’m writing you from a house of ill repute in Hong Kong. My reservations got lost and this lady said she’d give me a place to sleep—now I’m scared to go out the door!”

After his death, his wife Anne Morrow informed me I would be receiving the Lindbergh Award. She and her daughter were to make the presentation, so I told them about that letter and sent them a copy. I said I’d like to have Wally Schirra, if appropriate from your viewpoint, read it at the presentation. I told her, “Slim says so many nice things about me that I can’t read the letter, it wouldn’t be appropriate. And it wouldn’t really be appropriate for you to read it, but it would be great for everyone to hear Wally read it.”

Everyone says Wally Schirra has a great sense of humor.

BH: He’s so wonderful in that respect. He read Lindbergh’s letter, and it was fascinating.

You’ve flown so many different planes throughout your career. If you had to pick two or three that were special, you know, like the way a couple of women over a lifetime can capture a man’s heart, which planes would it be? When you look back, which ones did you love?

BH: Did you ever fall in love and not like them (laughter)? Well, the F–86 is the one that stands out the most in my mind, the Sabrejet was it. I was in on the early testing; the spin tests and the dive tests. I’ve done that on a lot of different airplanes but the reason I choose the F–86 is because it was docile. Not in its early days.

Mig Hunter by Peter Chilelli

It killed a few people, but by the time we got it cleaned up we had a sweetheart—the most docile, nicest handling airplane you’ve ever sat in. The creature comfort was terrible, but the flying qualities were…perfection.

Have you ever had an accident during a show?

BH: Oh yes, sure! In the big Hanover, Germany, show I had to land a Sabreliner on one wheel as I couldn’t get the other one down. There was light rain. After touchdown I couldn’t hold it up on one wheel all the way down the runway. The wing started dragging and we departed the runway. Wiped it out. But I was back in another airplane 30 minutes later!

Do you know some of the early test pilots and NASA astronauts?

BH: All close personal friends of mine. Close to every one of them, flown with all of them.

Frank Borman?

BH: Top-notch dedicated American gentleman.

Neil Armstrong?

BH: Ditto.

BH: Well, he’s a real hero in my book. I knew him intimately. In his book, he wrote a lot about us, our togetherness. I was selected to fly the [Bell] X–1 before him! Of all the people I’ve ever known—you could not have done better than Chuck—the best aviator I’ve ever flown with, that’s a true statement. The feelings run deep, so does the admiration. I can assure you the success of that program (the X–1) could not have been any better accomplished than it was with Chuck at the controls. He’s the best aviator I’ve ever flown with. Great friendship, great admiration.

Would you say Chuck Yeager personifies ‘The Right Stuff?’

BH: He sure does, he sure does.

If someday, when you meet our maker, he says, “Bob, we’re going to make an exception. We’re going to let you go back to earth and live for one week.” How would you spend that time?

BH: That’s a very difficult question because when they take me to the undertaker, that poor guy is going to have a hell of a time getting the smile off of my face. I’m 50 lifetimes ahead of any other man who ever lived. I’ve had more fun and met more interesting people than you would ever believe. For many years I wore that business suit while performing. A black tie, a black suit, a white shirt, and people would ask why do you always dress like that?

Because you’re ready for the undertaker?

BH: No, not only the undertaker, but when I get out of the airplane I’m ready for the cocktail party! And then I’m going to save the undertaker all that trouble of trying to take care of me. Isn’t that a good philosophy?

Cockpit to Cocktail Party: The Bob Hoover Story. Could be a damn good book title!

And on that concluding note, a lot of laughter.

In 2002, I’m sure I expressed gratitude to Bob Hoover for taking the time to grant this interview. I’d like to say it again: Thank you Bob, it was a privilege. KB

****************************

Robert Anderson “Bob” Hoover (January 24, 1922 – October 25, 2016) was a United States Army Air Forces fighter pilot, USAF and civilian test pilot, flight instructor, air show pilot, and aviation record-setter. Known as the “pilot’s pilot”, Hoover revolutionized modern aerobatic flying and in many aviation circles has been described as one of the greatest pilots ever to have lived.

Hoover learned to fly at Nashville’s Berry Field while working at a local grocery store to pay for the flight training. After graduation from Isaac Litton High School in East Nashville he enlisted in the Tennessee National Guard and was sent for pilot training with the Army and served as a fighter pilot in the Mediterranean theater, shooting down a FW-190 before being shot down and captured, remaining a POW in Stalag 1 until almost the end of the war in Europe.

After the war he and Chuck Yeager were test pilots together at the Air Technical Service Command at Ohio’s Wright Field. He was the initial selection to be the first pilot to break the sound barrier in the Bell X-1 but became Chuck Yeager’s backup in the program and flew chase for Yeager in a Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star during the Mach 1 flight.

Hoover left the Air Force for civilian jobs in 1948. After a brief time with Allison Engine Company, he worked as a experimental test pilot/demonstration pilot with North American Aviation, While there, he developed a dive- bombing technique for the F-86 Sabre and traveled to Korea to demonstrate and teach the maneuver for pilots flying combat missions in the Korean War. During his six weeks in Korea, Hoover flew many combat bombing missions over enemy territory, but was denied permission to engage in air-to-air combat flights.

North American eventually sent him to US Navy Test Pilot School and he began performing carrier tests. Hoover flew flight tests on the FJ-2 Fury, F-86 Sabre, and the F-100 Super Sabre.

In the early 1960s, Hoover began flying the North American P-51 Mustang at air shows around the country but was best known for his civil air show career demonstrating the capabilities of Aero Commander’s Shrike Commander, a twin piston-engine business aircraft that had developed a staid reputation due to its bulky shape. Hoover showed the strength of the plane as he put the aircraft through rolls, loops, and other maneuvers, which most people would not associate with executive aircraft. As a grand finale, he would shut down both engines and execute a loop and an eight-point hesitation slow roll as he headed back to the runway. Upon landing he would touch down on one tire followed gradually by the other. After pulling off the runway, he would restart the engines to taxi back to the parking area. On airfields with large enough parking ramps, such as the Reno Stead Airport, where the Reno Air Races take place, Hoover would sometimes land directly on the ramp and coast all the way back to his parking spot in front of the grandstand without restarting the engines.

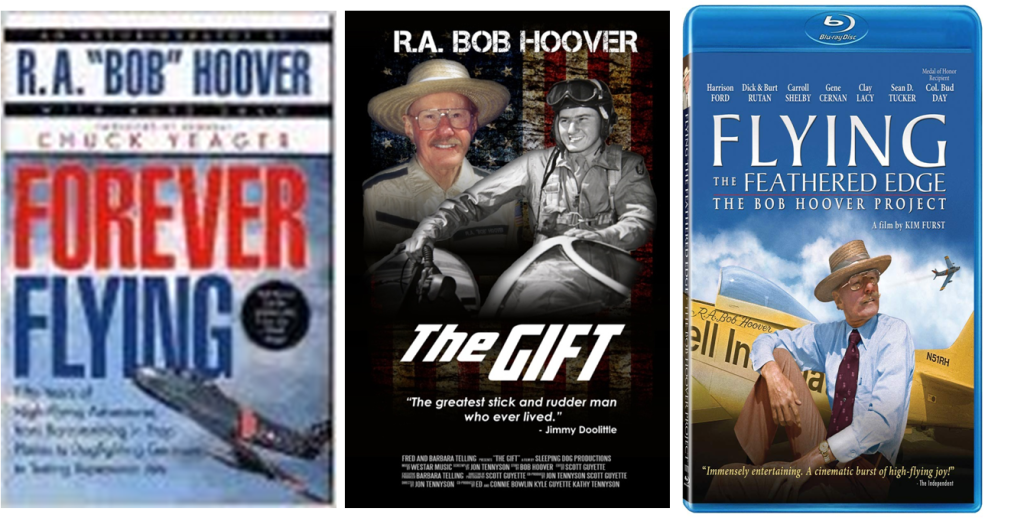

For further information on Bob see:

By age 19, Kathleen Bangs was already a flight instructor for one of the world’s top aviation programs. She has spent a career passionately involved in all facets of aerospace, with a particular dedication to aviation safety.

She’s a rated Airline Transport Pilot and former commercial airline pilot, airline training instructor and check airman, with over 10,000 hours of flight time spent flying aircraft ranging from large wide-body passenger jets to amphibious seaplanes.

Kathleen is an award winning aviation writer and journalist whose work has appeared in leading industry magazines and newspapers. In addition to flying and training pilots, she’s also led a number of creative marketing and public relations programs to support a variety of top aviation industry manufacturers.